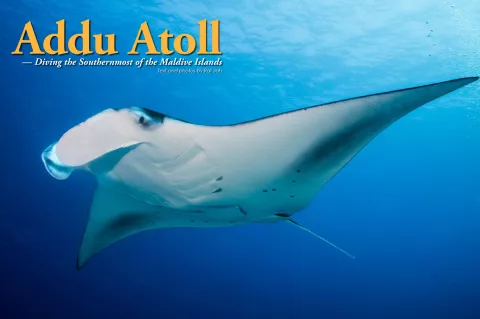

In the southern end of the Maldives lies the Addu Atoll, which hosts beautiful reefs, plentiful marine life, giant manta rays, sea turtles and crystal-clear waters. Raf Jah takes us on a journey to this diving haven, with a stop along the way to dive with tiger sharks at Fuvahmulah Island.

Contributed by

The morning of departure dragged on. I looked out again at the Indian Ocean and sweated some more. It really was an azure blue, but it was also humid, and I had been sitting for hours. The view from the pavement outside Malé’s airport has to be one of the most beautiful, but after an overnight flight and six hours on a hard bench, it was getting very old very fast.

Eventually, our check-in desk opened, and we were processed in that relaxed way that you will only find on Oceanic islands. We sat some more on slightly padded seats, sweated some more and then were crammed onto a bus that was far too small for all of us. We drove around the apron and boarded a battered 20-year-old Dash 8-300.

We taxied out, passed a row of incoming intercontinental jetliners, and then turned south. I finally managed to sleep, waking to see the most stunning coral reefs around the atolls below. A few minutes later, we circled a standalone island that had no lagoon. Descending over the sea, we bumped down on a short concrete runway, the propellers reversed their pitch, and we stopped outside a tiny hut. This was Fuvahmulah Airport.

The crew from Dive Point picked us up in their pickup and took us to the dive shop. All we wanted to do was sleep, but they insisted that we unpack and assemble our equipment. We did this, and then they told us our first dive would be in an hour. We protested and were taken to the hotel. We ended up diving a few hours later—just outside the harbour. This would be a baited tiger shark dive.

Diving at Fuvahmulah

The diving in Fuvahmulah was pleasant enough. With the exception of the shallow tiger shark dives, it revolved around “hunting” to catch sight of other species of sharks. This involved a great deal of blue-water swimming, spending a long time at a depth of 30m to avoid the ripping currents, and in the cases of some dive centres, dropping well below this legal maximum.

One German diver proudly showed me his computer reading of 50m.

“Did you see anything?” I asked.

“The shark swam away,” he replied, in a disappointed manner.

I would say that the tiger sharks were impressive, but the rest of Fuvahmulah’s diving felt a bit insipid. The island itself was stunning, with an inland lake and wonderful people and beaches, but it too lacked the tourist infrastructure needed for groups of divers. Simply getting a meal with hot food or a meal on time was a struggle. The Dive Point staff were extremely professional and had plans to open a guest house on the island to negate all of these issues. I would return to Fuvahmulah, but more for its charm and beauty than for the elusive deep-water shark diving.

Getting to Addu Atoll

A few days later, we boarded a speedboat, which bounded its way out of Fuvahmulah’s harbour and set a course southwest. An hour and a half later, we entered the outer sandbanks of Addu Atoll and stopped at a distant jetty. Some passengers got off, but we continued on our way to the main harbour at Feydhoo. This was the main terminus for people arriving on Addu Atoll by sea.

A minibus was waiting to take us to the Equator Village Maldives hotel. This was a comfortable but utterly unpretentious lodge by the sea. It had a quaint colonial feel to it. Our group of friends checked in and met the divers who had flown to Gan Island directly.

The group consisted of British divers from the Arabian Gulf, a contingent of three Canadians, two Americans and three divers from the United Kingdom. We all knew one another well. As my usual buddy, Francisca, was developing an ear infection and had to stay topside, I dived either with Godwin, the laconic doctor from Toronto, or with Paul, a down-to-earth computer engineer from South East London.

About Addu Atoll

Addu Atoll is a series of slightly larger islands (by Maldivian standards) that lie 620 nautical miles southwest of Colombo, 300 nautical miles south of Malé, and only 200 nautical miles north of the British Indian Ocean Territory. The heart-shaped atoll is made up of three large islands: Hithadhoo, Maradhoo-Feydhoo and Gan. To the east, smaller and thinner islands make up the right side of the atoll, offering a substantial and protected but deep lagoon. The islands of Addu Atoll lie just below the equator, with Gan Airfield at 0.69°S and 73°E. The southern tip of Gan is also the southernmost point of the entire Maldives.

Addu Atoll was different from the start. The hotel turned out to be the former sergeants’ mess of a Royal Air Force station. In the waning years of the British military presence in the Far East, India and Sri Lanka allied themselves with the Russians and Chinese respectively. They started to close doors to the Royal Air Force, and a new refuelling stop between the Middle East and Singapore was needed. The British Government chose the island of Gan. When the RAF left the tiny island in 1976, they handed over the only other concrete runway in the Maldives and a first-class working airport. As Gan was a commercial island and had no villages within its boundaries, the hotel was allowed to serve alcohol.

Diving

The next morning, we tipped out of the minibus at Aquaventure Dive Centre. We quickly sorted our equipment and boarded dive centre owner and master instructor Marc Kouwenberg’s dhoni (traditional wooden boat). Sailing out of the breakwater, we headed north to the nearest channel. The captain held the dhoni over the edge of the reef, and we clambered into our gear.

We entered the water with a giant stride and headed down to around 25m. Here, Marc started patrolling in a box-shape in the blue water. When he was satisfied, we dropped down and swam into one of the sides of the channel.

The visibility was 50m, and we could clearly see the school of sharks swirling around the far wall. We advanced on them gently until they were all around us. Then, after a few minutes, they disappeared—so we continued along the channel into the lagoon.

The current picked us up and spat us into a sandy patch. Marc signalled us to “hook on,” and we arrested our headlong flight into the enormous lagoon. Within a minute, a giant manta ray appeared and hovered over a large patch of coral. A fish came out and started cleaning the gills of the manta. Within a few minutes, there were seven manta rays taking turns in being cleaned. Our bottom time ran out and it was time to ascend.

Our next dive was along a stunning coral reef that started at 10 metres and sloped gently down to 35 metres. We swam along midreef and took photos of schools of oriental grunts.

The next few days of diving were a combination of channel experiences with sharks and ultra-steep walls in the northwest. The dives could be long, slow and relaxed, or sometimes deeper and more exciting. What made every dive so special was that we had no idea what we would see. We could be on a wall and then a 300lb tuna and its two mates would swim by lazily. On every safety stop, we had something special come by—be it a barracuda, turtles or eagle rays swimming past us.

“I don’t believe this place,” said Paul. “It’s like nowhere else on earth… You think the dive is over, but you still have to keep your eyes open to see what else is coming!”

Topside excursions

Between dives, we explored Addu. It felt as though we had stepped back in time, to an uncomplicated world, and perhaps a real view of the Maldives. The streets of Addu were spotless with its people polite and kind. When we went for a walk, we walked on streets of crushed coral. The people were welcoming and, as they were used to the occasional tourist, they had opened coffee shops, cafés and restaurants. Service was swift and the food excellent.

We strolled through the narrow backstreets in-between palm fronds and small cultivated gardens. If we took a wrong turn, we popped out onto even smaller dreamy lagoons, tiny clean beaches and fishing boats. On the eastern coast of Maradhoo and Feydhoo, there were impressive but small harbours. Cargo carrying landing craft and fishing vessels were tied up at the jetty. Now and again, one would trundle out of the breakwater to go about its business.

Uncluttered with concrete and with a truly relaxed atmosphere, Addu was quietly so much more efficient than Fuvahmulah. To me, the culture was reminiscent of the Arabian Gulf combined with a South Pacific Island.

MT British Loyalty

Perhaps the most intriguing of the dive sites around Addu was the motor tanker MT British Loyalty. It had been sunk by a Japanese mini submarine in Diego Suarez in Madagascar. The Royal Navy had stubbornly refloated it and pressed it back into service. In Addu, it remained the fuel depot for the Royal Navy Air station.

One night, a German U-boat found a way to fire torpedoes into the lagoon around the submarine nets. British Loyalty was hit and started to sink. The crew, assisted by the Royal Navy, managed to pump the water out of the vessel and keep it afloat. It served until the end of the war in Addu. Then, in 1946, surplus to requirements, British Loyalty was towed out into the lagoon and rather ignominiously sunk by the Royal Navy.

At 140m long and lying on its side, in 32m of water, with its hull a mere 14m from the surface, the British Loyalty is a magnificent dive. The hull has become a giant coral reef covered in hard corals and inhabited by schools of fish.

We descended slowly on its midships before making our way to the stern. Visibility here was around 10 to 15m. We finned along the lines of oil pipes, setting the depth that we were comfortable with, and taking care to avoid becoming snagged on anything.

The engine room had been completely blown open, and we all swam into the cavernous area. A huge Sulzer engine was covered in something. Paul and I swam deeper into the wreck and switched our lights to full power. There was a degree of rust particulate coming down on us, dislodged by our bubbles, but we could clearly see hundreds of yellow snapper swarming all over the engine.

We moved slowly around the room, with our lights illuminating the bent pipes, companionways and gauges. We had to descend to exit out of the great hole and turned towards the stern. Here, at around 28m, we found the huge propellor sitting sedately in front of the rudder. I looked down and saw a small debris field.

Then, with our bottom time running low, we made our way towards the top of the hull. At this point, at the “bottom” of the hull, it felt as if we were on a large coral wall, not a wreck. We did a safety stop at 6m, staring up and down the length of the vessel before surfacing.

Bodu Hola Wall

Francisca and I managed another dive on Bodu Hola Wall. We meandered along at 25m and nipped into a cave overhang to have a look. As we ascended, the usual massive kingfish came by and swam lazily off. Then, three huge tuna visited us. We started ascending to find ourselves amongst a dozen large sea turtles. We sat in the blue and watched them from a distance.

As we surfaced, we told Marc what we saw. “Oh, so you found Turtle Point,” he said, chuckling. “Sometimes, the current allows you to do that. It’s great, isn’t it?”

Soon enough, it was our last evening after our last dive. We sat around drinking coffee and eating cake provided by the Equator Village hotel and recounted our experiences.

“This is one of the world’s final frontiers of scuba diving,” I said. “It is not Papua New Guinea, but it has less dive boats, and it is literally boiling with fish.”

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” said Paul, in agreement.

“And thankfully, it should not get too crowded; there is only a couple of 40-seat planes a day and Air Lanka on the weekend,” I muttered.

What made Addu so unique were the positions of its channels. Oriented north-south, they created unpredictable currents, and this brought in the pelagics. Addu also had the best manta cleaning station I had ever seen, and was blessed with calm reefs, macro dives, very steep walls and 50m visibility outside the reef.

That evening, Marc and his partner, Jiji, joined us for dinner. Later in the night, he sat next to me, and leant over. “I love diving, and for me, this is it,” he said. His passion for diving was clearly palpable. He sipped his rum and Coke, and stared out into the darkness. “I want to show everyone the very best, and if you dive on the edge, you can see the best here in Addu.” His broad Dutch accent had a softness to it. He was not talking about the best of Addu, but the very best of diving—for he had found it here. He smiled and looked at me and said, “I love diving on the edge.”

Departing thoughts

The next morning, a 16-year-old Sri Lankan Airbus squeaked down on the concrete runway at Gan. This weekly flight brought a few more divers to Gan. Five of our party walked across the tarmac. I stared around at the almost deserted airfield. I wondered what the last RAF servicemen thought when they boarded their VC10 back to the Persian Gulf in 1973.

Inside the cabin, we were greeted by perhaps the tattiest, most uncomfortable aircraft that I have ever seen. The seat covers hung off, plastic panelling was hanging on by a thread, and worst of all, the seat in front was so close that it dug into my knees. But the airbus worked.

We thundered down the runway, took off in an easterly direction, and banked over the eastern walls of Viligili. I looked back at Gan and saw the runway dominating the island, the palm trees and the reefs. That view stayed with me for 105 minutes until we descended into cloud and crossed the Negombo Lagoon to land at Colombo, Sri Lanka. It was ironic that the closure of RAF Negombo created the Air Station in Gan. We had crossed 620 nautical miles over the Indian Ocean, from one point in history to another.