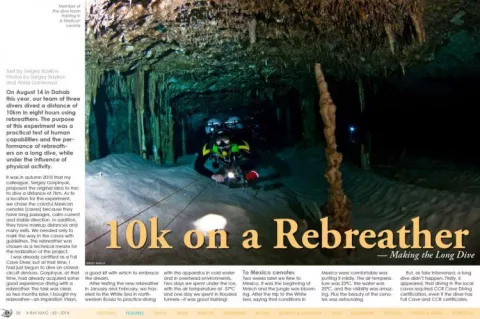

On August 14 in Dahab this year, our team of three divers dived a distance of 10km in eight hours using rebreathers. The purpose of this experiment was a practical test of human capabilities and the performance of rebreathers on a long dive, while under the influence of physical activity.

Contributed by

It was in autumn 2010 that my colleague, Sergey Gorpinyuk, proposed the original idea to me: to dive a distance of 7km. As to a location for the experiment, we chose the colorful Mexican cenotes (caves) because they have long passages, calm current and stable direction. In addition, they have markup distances and many exits. We needed only to mark the way in the caves with guidelines. The rebreather was chosen as a technical means for the realization of the project.

I was already certified as a Full Cave Diver, but at that time, I had just begun to dive on closed-circuit devices. Gorpinyuk, at that time, had already acquired some good experience diving with a rebreather. The task was clear, so two months later, I bought my rebreather—an Inspiration Vision, a good kit with which to embrace the dream. After testing the new rebreather in January and February, we traveled to the White Sea in northwestern Russia to practice diving with the apparatus in cold water and in overhead environments. Two days we spent under the ice, with the air temperature at -37ºC and one day we spent in flooded tunnels—it was good training!

To Mexico cenotes

Two weeks later we flew to Mexico. It was the beginning of March and the jungle was blooming. After the trip to the White Sea, saying that conditions in Mexico were comfortable was putting it mildly. The air temperature was 25ºC, the water was 25ºC, and the visibility was amazing. Plus the beauty of the cenotes was astounding.

But, as fate intervened, a long dive didn’t happen. Firstly, it appeared, that diving in the local caves required CCR Cave Diving certification, even if the diver has Full Cave and CCR certificates. To remedy the situation, we took three days to complete the additional course. During the training, we found out that the frames of our rebreathers were very cumbersome, and, in fact, we spent a lot of energy on overcoming the apparatus’ drag underwater. Moreover, our experience with the equipment was not a good one. However, the conclusion we reached at the time was that the trip to Mexico was not done in vain even though we had not completed the task we set out to accomplish. The “long dive” did not happen. But we did not let ourselves get bothered by the delay. The process of preparing was something we enjoyed.

Back to the drawing board

Periodically, we dived on our rebreathers, we made measurements and analysis of what was happening. I moved towards upgrading the supporting frame of my rebreather. The new construction allowed for the use of different tanks and, with the right approach, saved on weight as well as improved the streamlining of the apparatus.

I spent a lot of time making a plastic prototype, measuring millimeters of gaps and then made the product from stainless steel. I tested the prototype during one of our trips to Dahab in the spring of 2012 and I was satisfied with its performance. After that I made a titanium version, which was more robust and lightweight at 2.5kg.

Still, for greater streamlining, I moved my rebreather’s lung bags back to the shoulders. The idea was not new, but in the standard configuration of the Inspiration rebreather there were front lung bags. The manufacturers changed the trim, adding buoyancy to the shoulders and decreasing the buoyancy of the legs. This problem was especially felt in a wetsuit. We had to exert more energy to keep the horizontal position of the body. Well, of course, it was extra physical work and effort. I should mention that I made the shoulder lung bags in 2014 and tested them over the summer in the Barents Sea and in the Baltic. Indeed, it turned out to be a good and necessary device.

Gorpinyuk also worked on the project. For example, in the summer of 2012, he made a long dive in Dahab—lasting six hours. He proved that a long dive was really possible. Even then, he brought with him underwater some condensed milk snacks and water in plastic bottles, and he also worked out a surface detection system. Every hour he threw a buoy to the surface for three minutes. I also checked the performance of the rebreather. I dived in different conditions and with different lengths of duration underwater in various locations such as the Maldives, Egypt, the Barents Sea, the Baltic, local ponds, Orda Cave, and other locations.

Dahab

Conclusions were drawn and details were specified. And so it was on 14 August 2014 that we took the plunge for the “long dive” in Dahab. At that stage, Sergey Zakhvatov joined our team. He had been diving rebreathers since 2011. He was an athletic person with good sports facility. So The Three Sergey’s with three rebreathers set out, with three different configurations of frames, to test the physical capabilities of both human being and machine, on a long dive, compounded with physical exertion.

Despite the fact that all the equipment was prepared and checked the day before, we woke early and met at 6 AM at the dive club, Planet Divers. Once again, we tested the rebreathers, spoke about the details of the upcoming dive and coordinated the dive with a security team, which included a dive boat and a safety-diver, whose task was to observe the sea surface and always be ready to rescue a diver in need. At 8 AM we embarked onto the dive boat. After a brief administrative examination by the police, we headed out to sea. We sailed northeast along the coast. If you’ve ever been to Dahab, you know that the boats are moored in the lagoon, and the place of our entry into the water was 15km from the dock.

Taking the plunge

The site we chose from which to start the dive was El Bells, which is the most northern dive point in Dahab. For one and a half hours, we journeyed into the wind (in Dahab the wind is almost always ...

(...)