Aqaba sinks airplane for new artificial reef

On Monday, 26 August 2019, the former airliner slipped slowly below the surface, just south of Aqaba's main port, to become the latest addition to the already substantial number of artificial reefs along Jordan's stretch of Red Sea coastline.

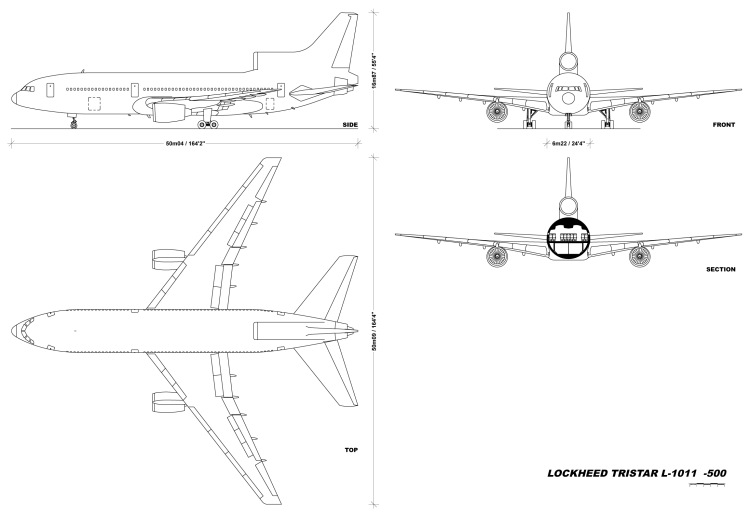

The TriStar plane is a commercial airliner that has been out of service and parked at King Hussein International Airport for several years. The Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA) recently purchased the plane with the intention of sinking it, and it was transferred to the main port to prepare it for is final role. The TriStar is the second aircraft to become an artificial reef off Jordan's coastline. In November 2017, a Hercules C130 was scuttled a bit farther down the coast.

The sinking

Many of the assembled members of the dive press were more than just a tad sleep-deprived, following a very late arrival into Aqaba the preceding night, but also upbeat and sat on port authority's comfortable vessel, observing the scuttling process as close as was safety permitted.

First the supports under each wing, which looked like miniature barges stacked with tires, were pulled away. For quite a long while thereafter, very little appeared to be happening. The plane was not sitting any deeper in the water. A couple of divers, or snorkellers, swam around the hull and were doing... something. I could not quite make out what they were fidgeting with. I suppose they were tending to lines and deflating flotation devices.

Then the jet started to lean onto its left wing, which floated for a while. At this point, we have probably been watching for three quarters of an hour already, but nobody was impatient, and there were plenty of cool drinks inside the air-conditioned lounge. Most of us with cameras wanted the best possible shot, so we climbed onto the flat roof of the vessel. It was a hot day—a very hot day—and the wind coming down from the desert was as hot as the air from a giant hair dryer, almost burning the skin. I was definitely happy that I brought my hat.

After another quarter of an hour, the exhaust of the jet engine under the tail starting going under, and it started to lean back. But still it did not go fast. I anticipated that the process would accelerate, as it did the last time I witnessed the sinking of an artificial reef, but this one sank quite slowly, even to the end. Very controlled.

After perhaps 90 minutes, the plane slipped completely under the surface and presumably settled gently on the bottom in the intended position.

First ones to dive the plane

The notion that we were the very first to dive the new wreck was not lost on any of us in attendance. When do you ever get to be the very first to check out a freshly sunken artificial reef?

The plane—or perhaps just all the particles stirred up—had been allowed to settle for two days after the scuttling before we were allowed to dive on it.

Painted bright white, it was easy to spot, as the dive boat moved into location and parked right above the tail fin. We were told planned depth at the front of the plane should be at 10-12m, and the tail at 25-30m. That was precisely where we found it. The tip of the tail stood up to about 12m. Hovering over the hull and wings that were still draped in some of the lanyards used for the sinking, the massive proportions of the aircraft became apparent. The engine intake at the tail was like a huge gaping mouth, ready to suck you in and swallow you whole. I did not venture inside, as I found myself uncomfortably underweighted—only later did I realise that the salt content at the top end of the Gulf of Aqaba is somewhat higher. I needed a whopping 13kg of lead, wearing a 5mm wetsuit, to be comfortable.

As the images show, we stayed on location all day so we could try diving the plane at night. Underwater, the white hull gave the plane a ghostly but quite photogenic appearance.

During our brief stay in Aqaba, we also got to dive some of the other artificial reefs and locations, which we will cover in more detail in a later issue.