I’m nervous. That’s not an unusual feeling for me when embarking on a challenging dive, yet I am in only two metres of water, the sea is flat calm, and there is no current to impede my progress at all. Indeed, the source of my apprehension lies just beyond the tunnel that I’m cautiously making my way through. I will soon emerge into a shallow pool known as Mirror Pond, and it is here that saltwater crocodiles are frequently sighted.

Contributed by

hey are the largest crocodilians on earth, and some say ‘the animal most likely to eat a human’. They are opportunistic hunters and will eat anything they can get their jaws on, even sharks. Sadly, it is this reputation as a man-eater and the high value of their hides that is putting immense pressure on their population, as is the case for so many of the world’s great predators. I have never dived with a ‘saltie’ before and the chance to photograph one in the wild was an opportunity that despite my nerves I could not forgo.

The photographer in me had fearlessly fitted an ultra wide angle lens meaning that I would need an extremely close encounter to get those coveted shots.

Despite every natural fibre in my body screaming at me that what I am doing is insane I continue into the tunnel. Behind me a fellow diver must have listened to her instincts as I catch a glimpse of her reversing out of the tunnel. Unfortunately it is, I have to admit with a slight element of relief, clear that the pond is not concealing the awesome hunter that we seek. However there was one more place to try.

As we move toward a dark, overhanging corner of the pond my heart again begins to race. I stop, my nerves forcing me to ponder my potential fate. It is then that I feel someone push past me. Di, one of my fellow passengers on the MV Spirit of Solomons, who only recently learned to dive, brushes past me torch boldly in hand, somewhat frustrated by the hesitating ‘professional’ in her way.

Coming to my senses I pluck up the courage and follow her in. So much for the wildlife photographer—when it comes to saltwater crocs, I’m reduced to following others. Alas, maybe just to further prove my humility, there is still no sign of the elusive croc. I can’t help but feel somewhat relieved.

The Edge of the World

Of course, the lure of such thrilling encounters is not compulsory when diving in the Solomon Islands—the true variety of diving here will satisfy all tastes, but the mere fact that saltwater crocodiles have not been dislodged from their natural habitat by man’s relentless expansion should give you a hint that this destination remains most definitely “off the beaten track”.

Indeed, the Solomons receives less than 15,000 visitors each year, of which only around a third are tourists. Compare that with a popular destination such as the Maldives, which at 1/100th the landmass, still accommodated over 675 thousand visitors in 2007. Even more exclusive destinations such as Palau attract over 85 thousand visitors a year.

With these statistics you could be forgiven for thinking the Solomons is at the edge of the world, but at only a 3-4 hour flight from Brisbane it is not difficult to reach. That said, there are places here both above and below the water that will simply make you feel like you ARE at the edge of the known world, so untouched by man’s influence are they.

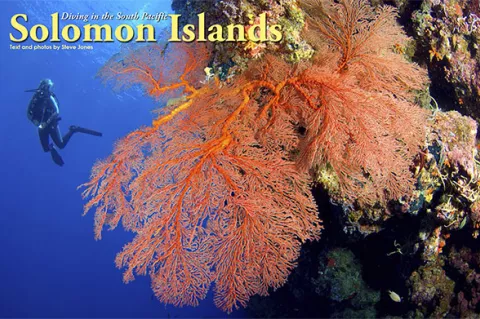

The nation consists of 992 islands lying to the north-east of Australia and the archipelago runs between Papua New Guinea to the north-west and Vanuatu to the south-east. The islands themselves are spread over a distance in excess of 1500 km and form part of the Pacific “Ring of Fire”, the volcanic region that encircles the Pacific Ocean basin.

It is this volcanic origin that has lead to some of the spectacular seascapes in these waters, which include huge caverns, crevasses and drop offs. Add to this the remnants of the Solomons historical past: this was the location of some of the fiercest battles of World War II with many of the wrecks within diveable depths, festooned with marine life.

Extraordinary biodiversity

Marine life, of course, is something the Solomons is renowned for. The marine biodiversity here is simply staggering. The Solomons is part of the “coral triangle”, the region with the highest marine biodiversity on earth which also spans Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines and Timor-Leste. During a survey in 2004 by the Nature Conservancy (http://www.nature.org/), over 494 species of coral were recorded in this region, making the Solomons second in the world only to Raja Ampat in coral species diversity.

The area is no less rich in fish life, with over a thousand species recorded here. A large number of sites exceed 200 species, which is considered the benchmark for an excellent fish count.

The diversity to be found underwater is not limited to the animal species.

One overwhelming impression that the Solomons left on me was that the diving itself is equally diverse, different not only from that to be found in neighbouring Papua New Guinea but even each island group itself differs, often drastically, from its neighbouring group.

From abundant macro life in the Florida Islands, you move to crystal clear waters, drop offs and labyrinths in the Russell Islands, before encountering spectacular big school action in Mary Island. There are resorts that offer local diving on a number of the islands, however the only way to encounter this true diversity is by liveaboard.

The Florida Islands

The Florida Islands are a small Island group to the north of the Solomon’s most famous island, Guadalcanal, and amongst others, the group contains the islands Nggela Sule (also known as Florida Island), Tulagi, Gavutu and Tanambogo.

The Floridas have become popular particularly amongst technical divers. Whilst the majority of the ships sunk in the Solomons campaign in World War II lie in the unattainable (at least with scuba) depths of the aptly named “Iron Bottom Sound”, there are still a number of notable wrecks that can be dived around the Floridas, with the destroyer USS Aaron Ward being at the top of most techies lists at a depth of 70 metres.

Wrecks however, make up only a fraction of what the Floridas has to offer. As a taster of what was to come, less than five minutes into my first dive in the Solomons, dive guide Phillippa Dean casually illuminates a pygmy seahorse (Hippocampus bargibanti) in her torch beam.

Out of the 50 species of seahorse so far identified, this is one of the smallest at only 2cm long. However, it is not only its size that makes it so difficult to find, it is supremely camouflaged to blend in with its gorgonian coral habitat. Indeed, the species was only discovered when a sample of the host gorgonian was being examined in an aquarium—so perfect is the pygmy seahorses’ camouflage.

It would have been all too easy to have spent the entire dive around this gorgonian, but that would have meant missing the rest of this dive on Tanavula point. This steeply sloping reef is home to countless critters and it’s an easy dive – a popular acclimation spot for the first day of a trip.

Amongst the group of expats I’m sharing the boat with, there seems a healthy obsession with “slug spotting” identifying as many nudibranchs as possible. It would seem we are in the right place: every nudi I see on this dive is new to me.

The Floridas offers the more challenging dive sites also. Passage Rock, as it’s name suggests, is a shipping hazard rising from deep water as if out of no where. It’s swept by strong currents and frequented by pelagics. Within seconds of dropping into the water, an eagle ray swoops in close before speeding off into the blue and dogtooth tuna patrol the upstream side of the reef.

The reef top itself has a healthy coral garden, but it is a struggle to hold our position as the current sweeps over the site. Despite my best efforts I’m put to shame by a green turtle that effortlessly glides upstream whilst I fight a losing battle and drift downstream.

The Russell Islands

How different the diving in the Solomons becomes after only an overnight steam. The Russell Islands lie approximately 48 kilometres north west of Guadalcanal and comprise of two main islands and a number of smaller ones. The water here is crystal clear, visibility in the 30 to 50 metre range and this area is all about spectacular seascapes: coral gardens, caves, drop offs and huge crevasses.

Dropping onto a site known as the bat cave, I’m distracted at the entrance by the discovery of an orangutan crab. This small decorator crab of around a centimetre gets it’s name from the mass of red hair that covers it’s entire body, which it uses both for camouflage and to help collect the plankton on which it feeds. It’s a tricky subject to photograph—the mass of red hair just doesn’t provide enough contrast for my cameras autofocus to lock onto easily.

Dragging myself away we swim into the large chamber and surface. I’d been warned by dive guide Justin Anderson to keep my mouthpiece in, not because the air is bad—there is a large opening in the ceiling allowing fresh air into the cave—but rather because the mass of bats are not a bad aim when depositing their guano, as a visitor learned the hard way a few years earlier.

Exiting the cave, the reef drops away steeply into very deep water. Large red gorgonians, whip corals and giant barrel sponges adorn the wall and it’s various ledges and amongst this spectacular vista a myriad of critters dwells: the biggest challenge for a photographer is whether to shoot wideangle or macro, but with either choice you wouldn’t go far wrong.

The bat cave is an excellent dive but it’s soon overshadowed by Leru Cut—one of the signature dives in the Solomons. It’s simply a jaw dropping experience. This chasm reaches some 100 metres into the island of Leru and the light was incredible, streaming in shafts down to the white sand floor through gin clear water. After the long swim in we eventually surfaced to see the roots of trees hanging down the steep cliffs from the encroaching jungle. Perfect.

The Russells isn’t just about caverns and caves however: the hard coral garden at Leru Bommies is without doubt the finest I’ve ever seen whilst another stunning dive is Karumolun Point. This site shelves down to a depth of 30 metres before dropping off steeply. It’s right at the edge of the shelf that we see grey reef sharks, including juveniles patrolling back and forth in the mild current. They of course, are no trouble at all, completely disinterested in us.

The same cannot be said for all inhabitants of this reef however, for whilst swimming towards the shallows, I feel a sharp tugging on my fin and turn sharply. No one in sight. Turning back I’m face to face with a large female yellow margin triggerfish.

Some species of triggerfish become aggressive when they have eggs—and it’s not just us human’s they’ll have a go at, any fish intruding into their area will be attacked. It’s a fair approach when you think about it—the triggerfish’s eggs are prime food for many predators—so the triggers are just doing what any animal would do, protect their unborn.

Fortunately for the trigger, and unfortunately for me, they are well equipped to defend their brood with teeth that are capable of crunching coral. Swimming upwards would be dangerous and serve no purpose, the trigger would simply follow me up. So, the only way is to move out of it’s defensive arc.

Alas this leads me straight into an even larger, and angrier resident—the titan triggerfish—well known for its aggressiveness towards divers. I swim out into the blue and give it a wide birth.

My tattered faith in fish is restored with the discovery of some of the most passive of marine creatures at the very same site. Firstly an ornate ghost pipefish, perfectly camouflaged to match the crinoid it shelters within, and moments later we, discover a halimeda ghost pipefish, camouflaged to the patch of algae it lives within.

Their exquisite camouflage serves to hide them from predators and also the tiny crustaceans they feed on. As with so many other areas of marine taxonomy, little is presently known about the natural history of these relatives of seahorses.

There are currently only five identified species in the Indo-Pacific, so observing two within metres of each other is a pretty special experience. Indeed, much of the uncertainty that surrounds the ghost pipe fish stems from the fact that they are so good at mimicking their surroundings; their incredible ability to camouflage themselves often makes it difficult to tell one species apart from another.

Karumolun Point is not alone in being the home for ghost pipefish in the Russell Islands.

They can also be found at White Beach—a site where the US forces dumped all their machinery off the piers before they left at the end of the war.

The site is now littered with artefacts: from trucks and cranes, to genuine 1940’s Coke bottles, and it’s muck diving at it’s best.

One of the more unusual inhabitants here is the archer fish. These expert shots catch their prey by stealthily hovering under the mangroves, then shooting a jet of water into the air at any unsuspecting insects crawling about above them. When the insect falls into the water, its quickly devoured. They’ve evolved quite remarkably—not only do they compensate for the refraction in the water, but they can vary the power of their shot for different size prey, bringing insects down from up to 1.5 metres above the water.

The diving in the Russell Islands impressed me. It was a mix of high octane, big seascape diving interspersed with incredible critter life. Before departing we made a visit to a Karumolun Island itself, and I can only say that South Pacific hospitality is something we should all attain to.

Our small group was greeted by the articulate village chief, Raymond, as we arrived, and the children presented us with the most beautiful necklaces of flowers, whose scent filled the warm air around us. Feeling more and more like visiting royalty, we were then treated to a magnificent display of dance and song by the women of the village. The tapping of their feet drove the rhythm and structure of their performance, which was enchanting and hypnotic, their voices melodic and soothing.

We are given fresh coconut water to drink, and as if to demonstrate the contrast and diversity surrounding the island, the men of the village begin their dance. This is a more powerful and strong display that reverberates with tribal passion, fierce and vigorous. To close this impromptu ceremony, everyone from the village joins together for one final performance, and we are left feeling humbled by the magnitude of the hospitality that was offered to us.

Mary Island

The edge of the known world—that’s what this place feels like. Below me, I can see a huge school of jacks swirling like a silvery grey cyclone as if threatening to suck our small tinny down to the depths.

As I don my mask, I look up and see a wall of greenery extending several hundred metres to the right of me, which then stops as abruptly as it begun—a startling emerald backdrop for the white outline of the MV Spirit of Solomons anchored before it.

There is nothing else in sight except the distant horizon of the Pacific Ocean—no ships, land masses, nor any other signs of human influence whatsoever. It’s all too easy to imagine this is the last human outpost, and everything that lies beyond is unknown, a wilderness. Welcome to Mary Island—as smile inducing a place as I have ever visited.

Dropping into the water, I slowly descended right into the heart of the jack school. They momentarily parted, and then I am engulfed as the school closes around me their silvery scales creating the illusion of liquid metal. It’s not even possible to take a picture; there are jacks everywhere, inches from my mask.

Dropping out of the bottom of the swirling mass, I’m distracted by a similarly sized school of barracuda only 30 metres upstream. The two schools keep a distance apart as if magnetically repulsed by each others rotation. The entire body of water here is alive with fish life. Reef sharks patrol the drop off, oblivious to the current that makes it so difficult for us land dwellers, whilst fusiliers frequently burst in unison avoiding the predations of the tuna that hunt them.

Mary Island (local name, Mborokua) is an extinct volcano to the west of the Russell Islands. It rises from deep water, is rarely visited and there are three sites here, all aptly named: Barracuda Point, Jackfish point and UTB, which, amusingly, means “under the boat”. As you can gather from the dive site names, big fish schooling action is what Mary Island is all about. Pelagics are frequently seen here as well as the resident, towering schools.

The Spirit allows open deck diving at this location; you can dive when you like, as there is no agenda to keep us motoring between sites. This gives a good opportunity to explore the third, and not to be overlooked site, “under the boat”. This site contrasts and compliments the exhilaration of the other two sites, for here is a wonderful coral garden alive with critters including leaf fish and ghost pipefish.

Marovo Lagoon

The Spirit of Solomons spent only a day moored at Mary Island on this trip. Part of me didn’t want to leave, and another part was eager to push on further and see what other treasures she would lead me to beneath these turquoise waters.

We departed and headed for the New Georgia Islands. For the next few days we’d be diving at Marovo Lagoon, the largest saltwater lagoon in the world.

Marovo lagoon is bordered by lush tropical islands with thick forest and mangrove. Ideal territory for saltwater crocodiles. It was nominated as a world heritage site, such is it’s significance, although that nomination was rejected due to the controversial and destructive logging practices going on here—an issue that hopefully in time tourism may help alleviate by providing alternate revenue sources.

Some of the most exciting dives here are to be found on the entrances to the lagoon. Kokoana passage is a drift dive along a vertical wall, following the current in. The reef simply explodes with colour, alive with undamaged gorgonians and soft corals. Fish life is also rich here.

A school of over 20 humphead parrotfish seem to follow me the whole dive. These are the largest of the parrotfish family growing to 1.3 metres in length and can weigh over 40 kilograms. We also see a number of reef sharks but it’s not unusual to sight pelagic species such as hammerheads here.

Shark populations in the Solomons have declined in recent years, along with just about every where else on the planet as mankind’s abominable lust for sharks fin soup is pursued. Nonetheless, shark sightings are relatively common here, at least for the time being.

That night, we moored on Karunjou Island, and it wasn’t too long before black tip reef sharks gathered at the back of the boat. Over the years, they have become used to the Spirit of Solomons and her sister ship, Bilikiki, throwing fish scraps overboard whilst moored, so they assemble for a free dinner. This also provides an opportunity to snorkel with them—this normally quite shy species is a lot easier to approach without the noise of a scuba set.

Mooring up at Peava Island gives a chance to off gas a little and experience a little shopping, Solomons style. The Solomon Islanders are famous for their wood carvings, and on the jetty, every carver in the vicinity has gathered to display their work.

The carvings being shown are works of art, formed meticulously from ebony, kerosene, sandal wood or coconut in the shapes of manta rays, sea shells or the distinctive “nguzunguzus”—classical figureheads that were used to decorate canoes to ward off evil spirits. Bartering here is not common and there is an etiquette to be followed in the whole transaction.

With a voice no louder than a whisper, I ask the price after complimenting the carver on his craftsmanship. The price is quietly stated by the carver. I then ask for the second price. After a little thought, the carver quietly responds —and that’s as far as the barter goes, any further would serve as an insult to these craftsmen.

The deal is done, money is discreetly exchanged and we bid farewell. It’s all so very far removed from the boisterous dealings to be found in the bazaars of Egypt, but no less enjoyable.

Our final dives in the New Georgia Islands take us to some of the relics of the war. The unidentified Japanese cargo ships, known simply as Japanese Maru 1 and 2 were bombed by allied aircraft and sunk at their moorings whilst supplying Japanese forces in the area. A field gun lies on the deck of one of the ships and an anti aircraft gun points defiantly at the sky on another, both the colour of a rainbow, they are so encrusted in coral.

The wrecks are a haven for marine life and even the submerged mooring buoy is covered in life—sea spiders, tiny decorator crabs even blenny’s live on the coral encrusted sphere, no bigger than a football. Safety stops have never been this interesting.

The Solomons possess incredible variety underwater—walls, caverns, critters, big schools, large animals and, of course, an abundance of wrecks, each of which has its own story to tell. The country displays a raw unrefined edge—far more exciting than the sterility to be found in mature tourist destinations. It is one of those places that has so much to offer but is seen by so few, and this simply adds to its appeal. ■

Special thanks to Bilikiki Cruises (www.bilikiki.com) and the crew of the MV Spirit of Solomons for their support in the production of this article. More of Steve Jones’s work can be seen at www.millionfish.com