Rico Besserdich is a widely published German artist, lecturer, photography instructor, writer, adjudicator and professional underwater photographer living in Turkey. His work has appeared in over 300 magazine and book publications around the world and has been translated into nine different languages. A CMAS/IAC Instructor Trainer with 5,000+ logged dives, he gives presentations at various photography-related events, universities and dive shows in Europe and has displayed his work in several fine art photography exhibitions.

Contributed by

PS: Music and photography are both expressions of waveforms, sound and light. In both art forms, we talk about expression, composition and mood. You are a lifelong photographer and musician. What are the similarities, as you experience them? Does one art form take inspiration from the other in your creative work?

RB: For me, in both art forms mentioned, the process of creation has the same importance as the end result. In other words, “doing it” is an important step of any artistic process, and as such, is a part of the art itself. All good artists know, we will do it wrong a million times before getting it right. But that is just part of the process, and hence, elementary for the quality of whatever we might present as a “final” result.

The art begins with the very first step of just doing it, whether it is the first note played on an instrument or the very first shot taken with a camera.

Four years before I became a professional musician, I took private lessons. Learning to read scores was a part of it. The first song I played from a score was “The Girl from Ipanema” (written in 1962, music by Antônio Carlos Jobim and Portuguese lyrics by Vinícius de Moraes).

In the original tune, the bass plays only half-notes. Meaning, in a single 4/4 measure, the bass plays only two notes. I asked my teacher, “What is the point in this boring thing? I want to play something cool!” He answered, “It all depends on how you play your two notes. The ‘how’ makes the difference.”

Photography feels very similar to me. In photography, you can make one and the same scene, or subject, into a visual rock song, a waltz, or a symphony—metaphorically-speaking. It all depends on how you play your “notes.” This includes playing it wrong, or “not right,” so to speak. The path to mastery is a very long one; I have experienced this in both music and photography. Actually, for those who keep an open mind, all art forms inspire one another endlessly. Everything is always moving and shifting.

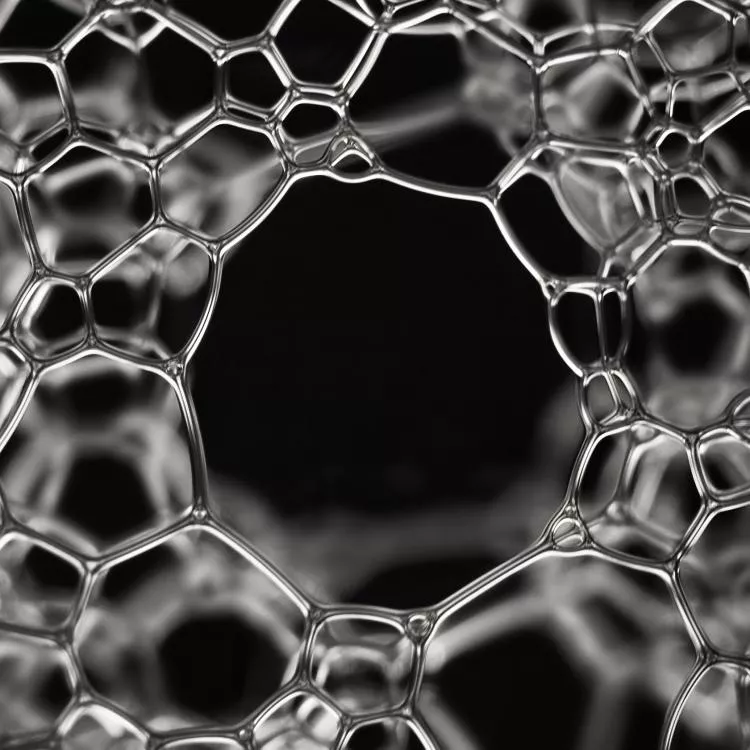

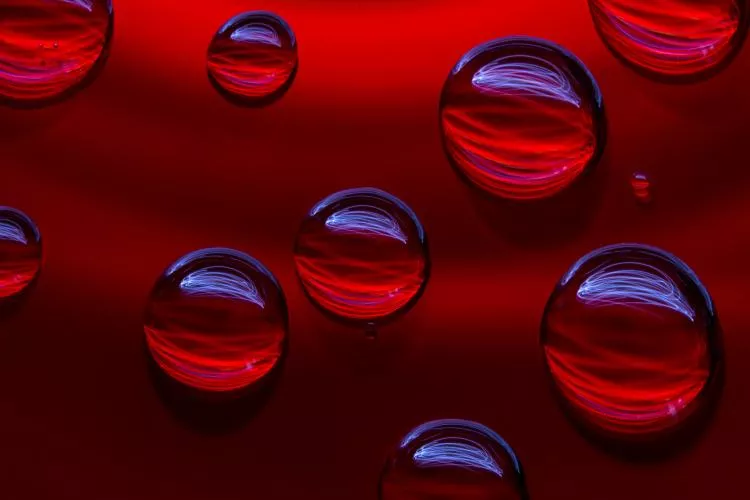

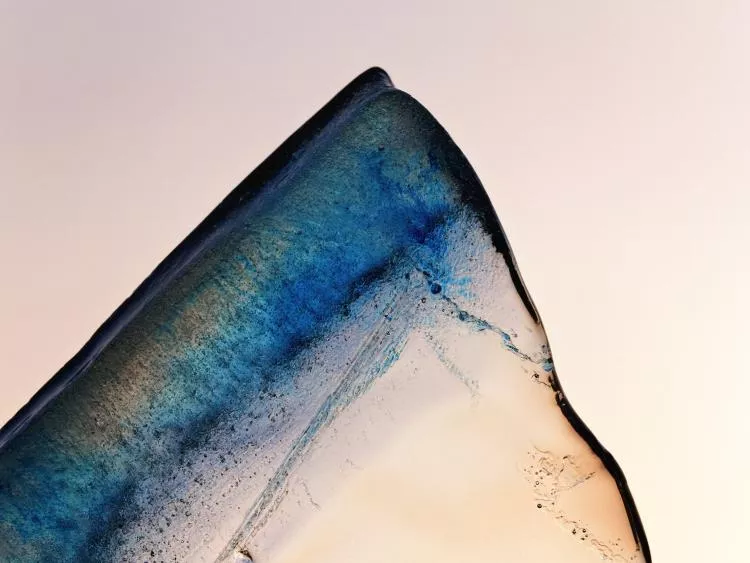

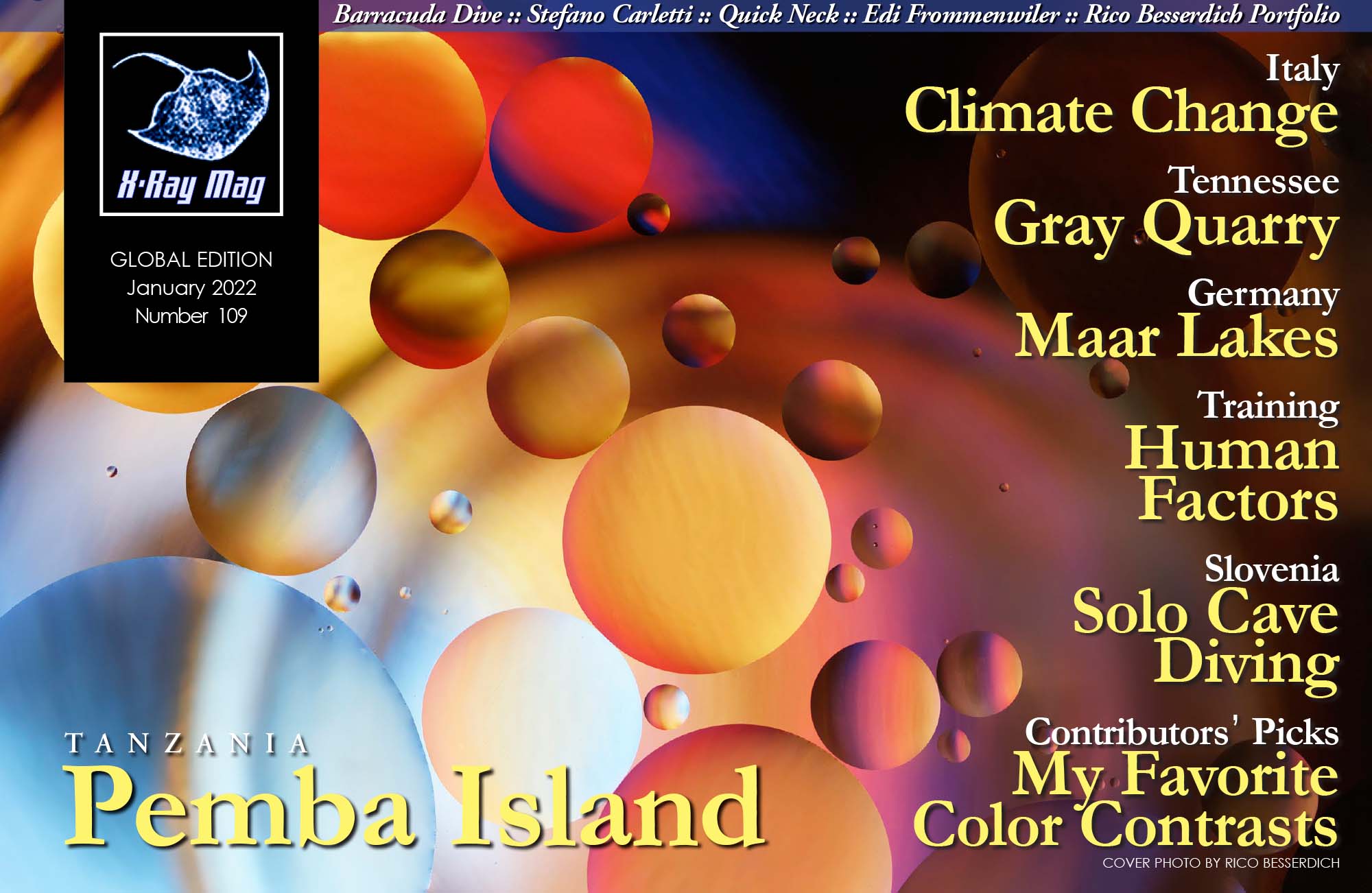

PS: In your books, you seem to have focused a lot on basic shapes in nature such as drops, bubbles, ice crystals, etc. Is this just an aesthetic choice or artistic exploration, or is there also an educational aspect?

RB: The only educational aspect of my images may be that Nature itself is the greatest artist, and water is one of her favourite brushes. This kind of fact does not need to be taught; it goes straight to the heart and soul of anyone who has an open mind for this kind of message. Regarding my water-related images, most of them are the result of artistic exploration. Water has its own will anyway. I cannot force or stage much in this medium. I can only explore, trying to capture those little liquid wonders.

PS: Throughout much of history, scientists and artists were often one and the same people. You have touched on this ancient kinship between art and science in some of your photo tutorials, such as the one about the relationship between Fibonacci numbers, patterns in nature, and compositions in art. How much influence or inspiration do you find in science, or in other arts?

RB: This is just my personal opinion, but I tend to say, whilst science tries to find answers to questions, art creates questions—or at least, it provides room for one’s own interpretations, which then is not something much liked in science.

But I certainly do agree that many known artists are very good observers. They might use science to simply understand things better, and such deeper insights certainly reflect in the art created. Just take the art of the great master Leonardo da Vinci as an example, whose well-known work, “Vitruvian Man,” is also a perfect match to the Fibonacci numbers.

To me, not everything needs an explanation—especially not a scientific one. I prefer to create new questions, providing my viewers room for own interpretations and feelings.

There are, of course, some artists I personally find inspirational. But when I create something, I simply disconnect myself from everything else. Inspiration is good, but influence is not, as this would bias me and my artistic work. First, I create. Then, I (in some cases) might think about how all of it can be explained on a logical level. But the latter, is not that important to me. Yet, I still love the Fibonacci numbers and have highest respect for all science.

PS: Can images be both documentary and artistic at the same time, or do we always have to make a choice?

RB: No, there is no need to make a choice. Many photographers mistake the term “artistic” with something that is connected to specific techniques, tricks or even image manipulation. So, if underwater macro photography purists say it must be f/16 and nothing else, but you do the shot with f/3.5, does that make you or your image “artistic”? No, because you just chose a different technique.

A very good example of an image that is both documentary and “artful” is the well-known “Napalm Girl,” created by Nick Ut in 1972. This image is so “documentary” that it even shuffled governments and made the entire world re-think the Vietnam War. And at the same time, it is very artful, or artistic, because it fits many of the criteria that are crucial in imaging arts, including that it is technically well done, has a clear rhythm and great composition, and it awakens emotions and raises questions.

So, yes, of course images can be of documentary value and artistic at the same time.

PS: You are also an acclaimed underwater photographer but seemed to have moved past traditional or mainstream underwater photography to instead focus on the aforementioned basic shapes and compositions. Has traditional underwater or travel photography come to a standstill or is there just limits to what can be done while staying true to the reporting aspect of doing an article on either a dive destination or animal life? Can underwater photography further evolve, do you think?

RB: This is just my very own path and personal way of doing things as an artist. To me, development is crucial. We always must go on. There is no point in repeating things we already know, again and again. That is why I moved away from the style that some might call traditional underwater photography.

But back to traditional underwater photography (or travel photography)… I believe, as long as people like to dive and travel, and are curious about the wonders of our oceans, this sort of photography will always have a serious role to play.

Of course, we have seen a lot of great underwater photographs of many dream destinations, underwater and above. However, it is an almost traditional mistake of many underwater photographers to believe that everyone else knows (and has seen) what they know (and have seen).

Every year, thousands of newly certified scuba divers want to know where to go for diving. Even though, underwater and travel photography often repeats itself (almost everything is already well-documented in images), we should never forget the person looking at one’s images in a magazine or somewhere online now, who was perhaps not even interested in diving or travelling at all last year. These people do not look at back issues, older articles, and photography publications published one to five years ago. They are “hot” now, they want to know it now, therefore, they will refer to images that are available now.

That said, as long as people can and want to travel and dive, there is a strong need for photographs that show what can be discovered, even though some of the older folks might have seen similar-looking photographs already, in older publications.

Underwater photography perhaps could evolve in terms of image expression. When judging or reviewing images at art universities or fine art photography competitions, my colleagues and I always have the same question (for the students or contestants): “What is the message?”

Very often, images are technically very well done but are missing a message—something that makes viewers think twice and reflect deeper about an image. A beautiful image of a beautiful fish will be just another beautiful image. The internet is already full of them. Many underwater photographers need to understand that high-end gear, fancy locations or interesting subjects to shoot (fish, wrecks, etc.) do not automatically create a meaningful image, or an image with a message.

As I often say, the better image does not need a better camera but a better photographer. That said, technical aspects such as a better camera, lens and/or techniques are actually secondary. The primary aim is to awaken emotions and needs, making people think twice.

PS: You have also served as a judge in many photo competitions. Which long-term trends or evolution have you observed over the years, and has underwater photography evolved towards the better over time? Do photo competitions still serve a purpose, so you think, or it is a spent format in need of a fresh rethink?

RB: During the past few years, I have observed that some major photo competitions now place more value on the aspect of environmental protection. Everyone can create a beautiful image of… whatever, but only few can add an extra message to such an image. When shooting an image and claiming yourself to be a photographer, you are simply expected to know your craft. Knowing how to use a camera is only of little value; it is considered self-evident.

Several photography competitions now support this idea—a development I highly appreciate. That said, photography competitions still serve a great purpose if they do their jobs right.

I personally believe that underwater photography has indeed evolved to the better. I find that nowadays more underwater photographers have become braver, even experimental, leaving some classical rules behind and creating something new. This is no surprise to me at all; I simply love this type of development. Furthermore, I enjoy seeing underwater photographers include environmental matters as a key message in their images.

PS: If you could use only three short sentences, what advice would you give to aspiring photographers—underwater or otherwise?

RB: 1. Enjoy your journey. Just doing it, is the real thing!

2. Something like “the best image” does not exist. Your best image is always the one you will shoot tomorrow.

3. Quoting Ansel Adams: “I don’t take photos. I make photos.” Just do the same, and you will be all right.

PS: A camera is just a mechanical tool. Art is an interpretation. How would you teach and train somebody to have an eye for creating interesting imagery? Is natural talent a prerequisite or can the right tutor and putting in the required effort take one all the way—to become a good, or even successful, artist?

RB: In my experience, as someone who once taught art at a university, and is still conducting (private) one-on-one lessons (yes, you can book me), I tend to say that everything is about sensitisation.

In my humble opinion, a good way to teach the “creative eye” is to open the senses of students to small but important details. Artistic people see and sense things others do not.

Yes, from my own experiences, I can tell you, tutoring helps a lot if the “chemistry” between the tutor and student is well-balanced. Mastering the craft (such as learning how to use a camera, how to shoot portraits, architecture, nature, etc) is something we can learn from books, video tutorials and by just practising (a lot!). The eye for creating interesting imagery is something that can be learnt too, but that works better with a tutor as a coach or guide.

Talent might still play a role, yes. However, many art experts say that talent counts for just 10 percent of success, the other 90 percent is just hard training over a longer period of time.

PS: From where do you get your inspiration? Is it something you seek? Does it arise out of creative experimentation, or is it something that tends to happen to you in the course of life—encounters with other people or things you study or read?

RB: Seeking inspiration is something that does not work for me. There is no need to seek it anyway, as I am surrounded by it all the time. As water is my element of artistic expression, I can find inspiration everywhere where water exists. Reflections on the water’s surface, rain, fog, clouds, ice cubes in my deep freezer, or just water splashing in my kitchen sink while I am cleaning dishes; I am surrounded by a continuous flow of inspiration. When outside or even scuba diving, I often observe just the colours of water and how the sunlight creates magical patterns on the sea floor. This too is a great inspiration.

In terms of getting inspired, I prefer to “read” nature and light—that is all I need.

PS: What is the most interesting or promising photography (or photographer) you have seen lately?

RB: Not “lately,” but over many years, I have followed the work of photographer Angel Fitor of Spain, who I consider to be one of the most interesting (underwater) photographers. His images are of such a profound aesthetic, whilst still serving as invaluable documentary at the very same time.

Fitor has a gift for creating astonishing art works out of objects that are actually very common. Moreover, he has a very unique style. You can just look at one of his images and instantly know it is an Angel Fitor photograph. There is no need to read the copyright or the photo credit. This kind of uniqueness defines a true artist.

PS: Can art be defined? What is your definition or concept of what constitutes art?

RB: Whilst many creators (in photography or elsewhere) believe their pieces certainly must be art, the main principle always remains the same. It always needs two to make art: The creator and the beholder. Anyone can claim to be an artist. Yet, if nobody else sees art in it, such an artist would be a very lonely one.

Just in my personal opinion, I tend to say art is something that makes people think and, ideally, reflect on specific matters in life, nature and social environments. There is no need to completely understand art; real art does not really want to be completely understood anyway. Art creates questions, not answers.

But the moment you look at something and your brain creates new synapses, leading you to really start to think about it, and then share your thoughts with someone else, this is where art evolves. Art evolves when people start to talk about it. That does not mean that everyone needs to agree. They can talk, even argue, or discuss. They can hate it or love it. This all does not matter. What matters is that good art makes people think and talk, and by that act, the art itself evolves. ■

For more information, please visit the photographer’s website at: maviphoto.com.