—A rare look behind the making of an iconic image. From conception of the idea to the execution, you will be surprised how little of it was left to chance.

Contributed by

Factfile

Aaron Wong is a widely published underwater, fashion and commercial photographer based in Singapore.

For more information, please visit:

www.aaronsphotocraft.com

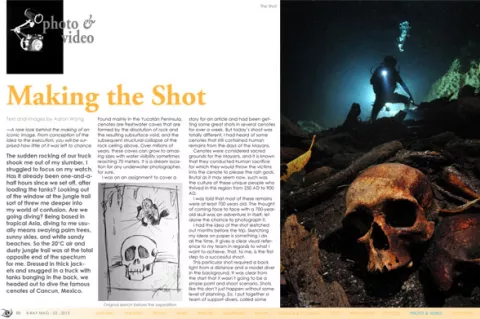

The sudden rocking of our truck shook me out of my slumber. I struggled to focus on my watch. Has it already been one-and-a-half hours since we set off, after loading the tanks? Looking out of the window at the jungle trail sort of threw me deeper into my world of confusion. Are we going diving? Being based in tropical Asia, diving to me usually means swaying palm trees, sunny skies, and white sandy beaches. So the 20°C air and dusty jungle trail was at the total opposite end of the spectrum for me. Dressed in thick jackets and snugged in a truck with tanks banging in the back, we headed out to dive the famous cenotes of Cancun, Mexico.

Found mainly in the Yucatán Peninsula, cenotes are fresh water caves that are formed by the dissolution of rock and the resulting subsurface void, and the subsequent structural collapse of the rock ceiling above. Over millions of years, these caves can grow to amazing sizes with water visibility sometimes reaching 70 meters. It is a dream location for any underwater photographer, for sure.

I was on an assignment to cover a story for an article and had been getting some great shots in several cenotes for over a week. But today’s shoot was totally different. I had heard of some cenotes that still contained human remains from the days of the Mayans.

Cenotes were considered sacred grounds for the Mayans, and it is known that they conducted human sacrifice for which they would throw the victims into the cenote to please the rain gods. Brutal as it may seem now, such was the culture of these unique people who thrived in this region from 250 AD to 900 AD.

I was told that most of these remains were at least 700 years old. The thought of coming face to face with a 700-year-old skull was an adventure in itself, let alone the chance to photograph it.

I had the idea of the shot sketched out months before the trip. Sketching my ideas on paper is something I do all the time. It gives a clear visual reference to my team in regards to what I want to achieve. That, to me, is the first step to a successful shoot.

This particular shot required a backlight from a distance and a model diver in the background. It was clear from the start that it wasn’t going to be a simple point and shoot scenario. Shots like this don’t just happen without some level of planning. So, I put together a team of support divers, called some local guides who might know of such a cenote, got my model—David, who is of pure Mayan decent (it seemed only fitting)—and off we went.

The expedition

They say that getting there is half the fun. Or is it? As it turned out, some of these cenotes were way off the beaten track. Most were owned by the original family who owned the land. These were mostly not open to the public, let alone photographers with big cameras. Even if they did allow divers, there were those who did not allow cameras, as these cenotes were still considered sacred to the Mayan decedents who still lived there.

How else do you explain 700-year-old remains that are left untouched all this time? In some ways, I’m glad they are not open to the public or divers.

We finally found a cenote that allowed us in, and yes, it was one of those places in the middle of nowhere— hence, the one-and-a-half-hour drive! Being so isolated meant that we had to bring all that we needed—twin tanks, gear, cameras, lights and all.

The truck finally stopped at a small village at the end of the trail where we could drive no more. We rigged up our equipment and had to hike the rest of the way. Passing by the villagers, we must have seemed like visiting aliens.

I was expecting some walking, but I wasn’t counting on it to be almost a mile long. I can assure you that carrying tanks and a full camera rig with spare lights through uneven jungle terrain isn’t exactly a fun thing to do. Whoever said that getting there was half the fun surely hadn’t been here!

We arrived at a small opening in the ground in the middle of the forest where the locals had built a small platform and simple rope systems for access. I went to the edge expecting to see water, but instead, what greeted me was a 25-meter drop. That sort of explained the need for ropes.

Looking closer, I realized it wasn’t just a shaft but a big cavity in the ground measuring some 35 meters across. It then dawned on me that the very ground I was standing on at the edge actually had nothing underneath it but a 25-meter drop! We were standing on ‘ground’ that was a mere three meters thick! It kind of sent a chill down my spine.

If not for this small two-meter opening, I would never have guessed the ground around me covered with trees was just a ‘crust’. It makes one wonder what else lies beneath.

We had to strap on harnesses and repelled down one at a time. My guide went down first followed by me, two other support divers, and lastly, my camera rig. It isn’t everyday you get to see your camera rig, strapped in whatever way possible, lowered down to you with a thin rope 25 meters over head. I wished I had a spare camera with me just so I could photograph that scene!

The cavern opened up to its full width, as I repelled past the three meters of surface rock. I could see the roots of the trees above dangling from beneath, some even making it to the water 25 meters below. It was a magical sight, and it made me feel so small in this world of giant trees and rocks.

Looking at all the effort it took just to get the camera here, It was as extreme as underwater photography can get.

Waiting in the water for the rest of the crew and equipment to arrive was a surreal and almost eerie experience. Knowing that human remains lay beneath me didn’t help either. I was almost afraid to move my fins!

Looking up at the small opening above, I wondered if this was the last thing these unfortunate sacrificial victims saw some 700 years ago. Who were they? Prisoners of tribal conflicts or volunteers from within the community? It was a powerful place to be in—a place of such history and untold suffering. It made me feel even smaller.

In the cenote

We descended to about 20 meters and searched through the maze of branches and logs. It was pitch black and our touches did little to help, as the slightest movement stirred up the sediment.

Unlike the ocean, this was a stagnant body of water, which meant that any sediment that was stirred up took forever to clear. The slightest movement kicked up rotting leaves that covered the bottom. Think of it as fine tissue paper in still water. It was a tough challenge to get around, and it took perfect buoyancy control to a whole new level.

I was told there were seven sets of skeletons within this cenote. Finding the right one in the right angle for the shot within the debris wasn’t easy.

Once we located the right skull, everyone moved back to prevent any stir ups. My model knew exactly where to position himself based on our pre-dive briefing. He stayed perfectly still as a support diver positioned directly behind him.

I hovered slightly above my final shooting position, as I knew I only had one chance at it before the area around the skull got stirred up. I tested the lighting and exposure for a while, and when I was totally ready, I signalled to everyone, descended slowly to less than an inch from the skull, fired six shots, and it was all done.

It was tough getting so close to the skull without touching it the slightest bit. Let’s put it this way: it had been sitting in its final resting place in peace for 700 years, the last thing I wanted to do was disturb it!

As I moved my camera away, I took a moment for a really close look, eye to eye. I thought for a moment that I might be the closest anyone has been looking into those eyes in all this time—a mere three inches away. It raised more questions than fear, but I knew better than to overstay my welcome and left the skull in its dark watery tomb.

Getting out of that cave was a muscle wrenching tug of war for the support team on the surface and a painfully constricting experience for us. The harnesses weren’t designed for comfort, and when your entire body weight including your scuba gear rested solely on the harness, it was far from comfortable—something the guys found out the really nasty way!

Slowly but surely, we all immerged from the hole, back to the world of the living. It was one of those shots I wouldn’t soon forget. Considering the logistics and conditions, it was amazing how much effort it took for good pictures. I am glad I managed to capture a great shot out of it all, and I am grateful to the team who helped make it happen.

Now, all that was left was the one-mile hike through the jungle back to our truck, followed by a one-and-a-half-hour drive. One suddenly remembers that old saying again, that getting there is half the fun, but there’s nothing mentioned about the getting back part of it! ■