Nowadays, the name Yamashiro could have different meanings depending on where you come from. If you live in Los Angeles, a huge pagoda near Hollywood is the oldest structure in California and hosts a famous restaurant named Yamashiro or “Mountain palace” in Japanese. If you live in Kyoto, Japan, Yamashiro is the name of an area close-by.

And for the older generation, it’s also the name of a never forgotten Japanese battleship lost during WWII during one of the major battles of naval history, the battle of Leyte, October 1944. Finally, if you’re a scuba diver, you might have heard about the wreck of the HIJMS Yamashiro as definitely the most challenging shipwreck in the world, because of the remoteness of the location, the extreme depth and the very bad diving conditions.

Contributed by

Factfile

About the Author

Cedric Verdier is the founder of the TRIADE Project, established in 1999, discovering and exploring more than 20 virgin wrecks located in the south of France between 70 and 130m (230 ft) and 430 fsw. I

n 2002, he was the first diver to identify and dive the British cruiser HMS Manchester off Tunisia.

Amongst other dive firsts, he pushed the limits of the Sra Keow cave in Thailand in May 2006, using his Megalodon Closed Circuit Rebreather, to an Asia-Pacific cave depth record of 201m (660 ft).

He is currently planning the Yamishiro Project, an international expedition aiming to dive the Japanese battleship HIJMS Yamashiro sunk in the Battle of Leyte in the Philippines in November 1944 and resting at a depth of 200m (660 ft).

Cedric is a PADI Course Director and a Trimix Instructor Trainer for IANTD, PSAI, ANDI, DSAT and TDI. He spends most of his time teaching cave and mixed-gas rebreather courses at the diver and the instructor level.

He is a past Regional Manager for PADI Europe and DAN and has written five books and more than 150 articles about diving. As he is always travelling all over the world, you can mainly contact him by email at: info@cedricverdier.com

October 24th, 1944

Vice-Admiral Shoji Nishimura doesn’t like the way everything goes. Nishimura is known for his high respect of the orders. No matter what orders he had, he would carry them out even though they could result in the annihilation of himself and his command. For the time being, he doesn’t know that it’s exactly what will happen in the next few hours in the Surigao Strait.

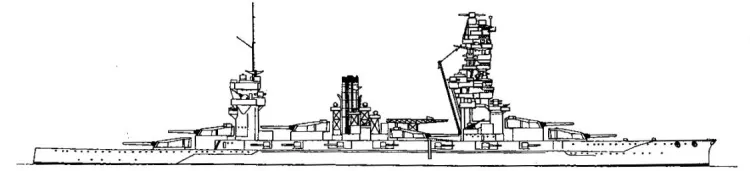

Only a year after being nominated as a Vice-Admiral, he is named commander of the Southern force of the Operation Sho-Go, as the Imperial Japanese Navy Headquarters in Tokyo search for a final and decisive naval battle against the Americans in the Philippines. His force (named Force C) consists of battleships Fuso and Yamashiro (his flagship), heavy cruiser Mogami, and destroyers Shigure, Michishio, Asagumo, and Yamagumo. And now, he has to go through the Strait of Surigao to attack the Allied invasion shipping in Leyte Gulf.

July 18th, 2006

Three technical divers and more than six hundred kilograms of diving equipment are boarding the boat that Rob Lalumiere, an American expatriate and an avid deep wreck diver, uses to provide the surface support to the Yamashiro Project team. A team made of three technical divers coming from very different horizons. I am originally from France but spend most of my time travelling around the world to teach rebreather diving. Pim van dem Horst does the same in his dive school in the Netherlands. Bruce Konefe, also an American citizen, resides and teaches technical diving in Thailand. We all come to Leyte, a remote island in the Philippines, to dive the Yamashiro and the Fuso.

Bruce and I spent the last ten months gathering information about the wrecks and the logistics that could be used for such extreme dives. We quickly both came to the conclusion that it’s a combination of heaven and hell.

Heaven because the wreck of the Yamashiro lies in pristine condition, still proud of her 213 m/699 feet length, her twelve heavy 14 inch guns and her famous 44 m/144 feet high superstructure nicknamed Pagoda.

Hell because the current is never less than 7 knots, the visibility on the bottom is close to 5m/15 feet, the maximum depth is almost 200m/656 fsw (only 160m/ 525 fsw for her sistership HIJMS Fuso, sunk in two parts only a few miles away). It also means that the team knows what a “Logistical nightmare” is.

There is no dive center to fill the tanks or rent some equipment. There is no recompression chamber less than twelve hours away. The closest boat available for technical divers, a private boat owned by Rob, comes from Ormoc, fifteen hours north. The closest town, Hinundayan, has only a few houses on a small road that looks like it is constantly being repaired, and more than ten people talking together at the same time is a major event in this very quiet area.

Everything has to be brought from Europe, Thailand or Manila. Soda Lime and small tanks for the rebreathers, spare parts, Helium, Oxygen... in short, an expedition as easy to set up as a wedding party on top of Mt. Everest.

Shooting a fish in a barrel

October 24th, 1944

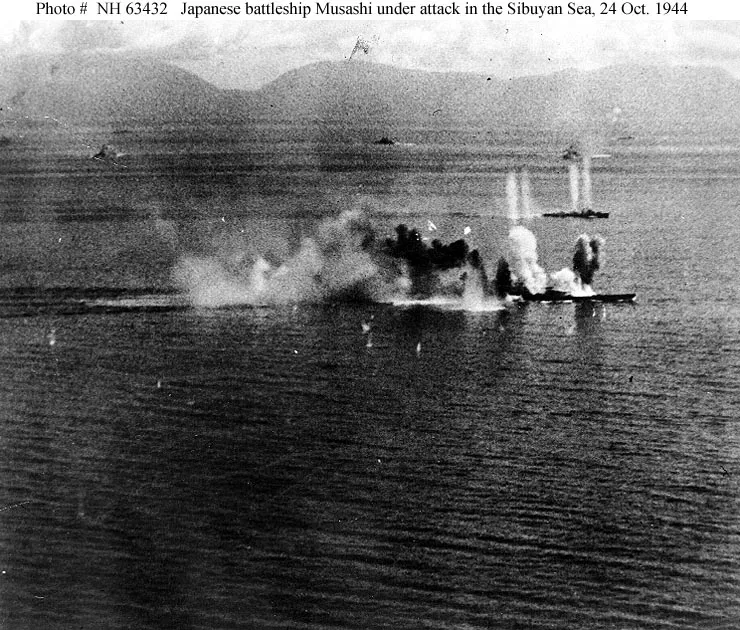

Since its departure from Brunei two days ago, Vice-Admiral Nishimura considers himself lucky, as his force has remained undetected by the US Navy. Unknown to him though, some aircrafts took off the USS Franklin to strike an attack on his ships. They are spotted a few minutes later, as they prepared to drop their bombs on the two battleships. Fortunately, the damages will be minor and nothing will happen for the rest of the afternoon. However, Force C has been uncovered, and US Navy ships from the 7th Fleet gather in the Strait of Surigao to welcome the Japanese fleet.

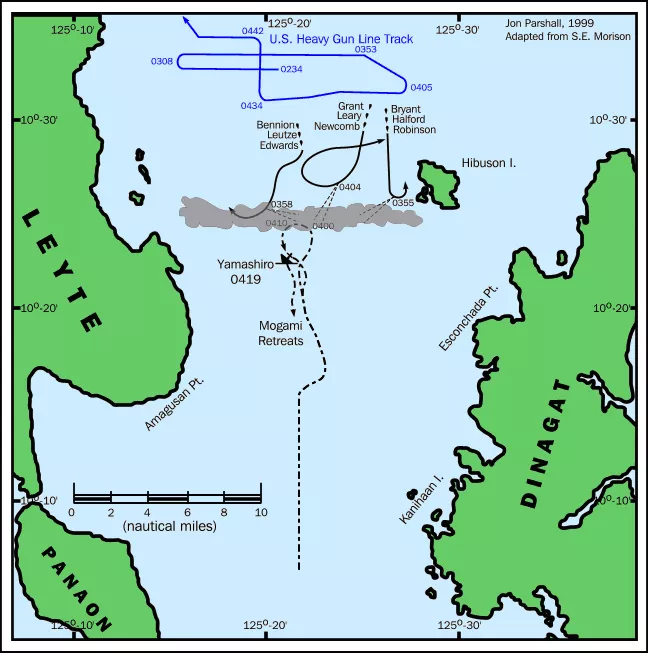

Its American opponent, Rear Admiral Oldendorf, had deployed his overwhelming forces to gain the maximum advantage, barring the Strait with an incredible layer of PT boats, destroyers, and finally, the great guns of cruisers and no less than six battleships. Amongst them, the deadly USS West Virginia, California and Tennessee, recently equipped with the new Mark 8 fire control radar, an improved system that better discriminated narrow targets in close proximity.

It’s late in the afternoon when Vice-Admiral Nishimura heads to the Strait. He is now well aware of the trap that is waiting for him, as a scout plane from the HIJMS Mogami has provided him with a report about the American forces and their location. Nevertheless, he knows that following the orders he has received will help Operation Sho-Go to succeed.

All of a sudden, US Torpedo Boats come from nowhere and directly aim at the battleships. As the night falls, the fight seems to last forever, finally ending around two o’clock in the night. But it’s actually only a pause, waiting for the next phase of the battle…

Then, an hour later, the US destroyers start to launch their torpedoes, hit the HIJMS Fuso, breaking her in two parts. HIJMS Yamashiro also takes a hit but keeps on firing from all guns, trying to find the enemy in total darkness. Most of the Japanese destroyers are lost or crippled by this time.

Another hour and the remaining American force is within range of fire. All the battleships, some being veterans of the Pearl Harbour attack, start a terrific concentration of gunfire, and every size of projectiles, from 6-inch through 16-inch, come pouring into the few remaining Japanese ships.

Shells come down like rain all around Vice-Admiral Nishimura. Nevertheless, he relentlessly keeps his force on its course, trying to make it through the Strait, even if he knows now that his command is doomed.

In the chaos of the night surface battle of Surigao Strait, the HIJMS Yamashiro is shelled and torpedoed into ruin, dangerously tilting on one side. Only a few minutes after the order comes to abandon the ship, the distressed ship suddenly capsizes and sinks stern first following a final hit from two torpedos in the starboard side amidships and aft. Aboard are Vice-Admiral Nishimura and most of her 1400 crew members.

There are only a few hundred survivors from the cut-in-half HIJMS Fuso, most of them refusing to be rescued by the US Ships, preferring to swim ashore to be butchered by the Philippines natives.

From all the Japanese Force C, only the cruiser Mogami and destroyers Asagumo and Shigure will remain operable. Every other ship had sunk.

Diving a mountain palace

July 18th 2006

Time to dive! So many problems are linked to the Yamashiro Project that it could be funny. Some bottom or support divers couldn’t come to the Philippines, due to professional, financial or personal reasons; a tropical storm named “Florita” (why such a sexy name for such a devastating climatic phenomenon?) flooded some islands and delayed the arrival of the team in Leyte; some equipment proved to be ineffective at depth, flooded, broke or were lost; even the boat had some problems and lost all the shotlines the crew set up; the helm broke and the boat drifted away; some electronics like the GPS or the depth sounder decided to display inaccurately and to switch off at the worst moment.

Even the weather played with the nerves of all the team members by alternating sun and rain, storm and gentle breeze; and finally the current, a ripping current, almost constant even at slack tide, was the worst enemy of the Yamashiro Project. The divers had to fight against it at the surface, during the descent and the ascent, and even on the bottom.

After a day of extensive search in the area, in order to avoid any confusion with other wrecks in the Strait of Surigao, the team was convinced that the huge profile on the echo sounder was the wreck of the HIJMS Yamashiro, as it also matches with side-scan sonar images and GPS locations found by previous expeditions (like the one conducted by the late John Bennett). None of these expeditions were able to explore the wreck, mainly because of the current, but they all came back with a lot of useful information.

After several attempts to hook the boat on the wreck, Rob and the team decide to drop a shotline on the wreck. Quickly, Eveline Verdier, one of the support divers swims to the buoys to remove the excess line. There is no slack. The current push everything so hard that it will be very difficult for her to set up the deco line with the stage tanks.

Pim, Bruce and I start to gear up. A long process with the equipment used: dry suit, rebreathers (Ouroboros CCR for Pim, Inspiration CCR for Bruce, Megalodon CCR for myself), bail-out tanks, etc...

Even with the boat very close to the shotline, the strong current makes it very hard for the divers to reach the buoys. At the surface, Pim has a 1st stage regulator O-ring that blows up at the last minute. The whole crew helps him to fix the reg, but it’s already too late. After having swum hard against the current at the surface, he decides to abort the dive.

Bruce, who had some problems with the Hammerhead, decided to switch back to the normal Inspiration electronics, therefore limited in depth. He will stop at 120m/393fsw.

Only I can descend along the shotline that is now at a 45-degree angle. The only way to go down is to pull myself with the rope. That’s the plan, but it’s quite hard work even with all the tanks side-mounted and a configuration as streamlined as possible. Several times I had to stop for a few seconds to catch my breath, even with a very efficient pre-production radial scrubber in my Meg.

At 120m/393 fsw, I meet a big thermocline and the temperature drops from a comfortable 29°C/84°F to a chilly 22°C/71°F. It becomes darker, and the current does not decrease.

At 180m/590 fsw, the line is horizontal—well above the bottom. I follow it and discover a huge hull. My heart is beating as fast as a runaway train. My canister light has flooded and I now rely on a 10W HID light. The beam is narrow and hardly covers more than a small part of the impressive wreck. A quick check at my instruments will tell me that I just finished a very long 14-minute descent!

It’s so dark and the wreck is so huge that it’s difficult to have any clue about where I am. Some superstructures are still intact, some are lying on the bottom. A tilted hull... It looks like the complete wreck sits on her side.

Unfortunately, after only a few minutes on the bottom, computers and tables clearly agree that it’s time to start an ascent that will take 6 hours to complete.

The current is still there, the line still almost horizontal, and it takes quite a while to reach the first deco stop at 150m/490 fsw.

Above the thermocline, the water is warm and the visibility excellent. Bruce is still deco-ing some 40m/130 fsw above. Because of the current, we both use a Jon-line to relax a little bit while maintaining a constant depth.

The support divers bring down a plastic bag with drinks and magazines. They also visit us to take some pictures. Everything looks fine, so far...

9m/30 fsw

The current is picking up big time, and I jump all over the place at the end of my Jon-line. It’s made in Thailand but it doesn’t break, fortunately, as other problems are waiting for me…

I suddenly notice that the oxygen level in my rebreather starts to drop.

The oxygen tank is simply empty because of the high exertion level, much higher than the worst-case scenario. Another tank is plugged in the rebreather and the oxygen is now manually injected. But it looks like the injector leaks, even after having been checked multiple times. Buoyancy control becomes a problem. I have to exhale a lot, and I am losing quite a lot of gas. It becomes even worse at the shallower stops... Another empty oxygen tank and one of the support divers has to bring a new one.

The last deco stop seems very long, filled with boredom and cold. The drysuit is full of water because of the last two hours of me spinning around at the end of the Jon-line like in a washing machine.

A very slow final ascent and I reach the surface in a place that looks like it’s in the middle of a storm... A lot of wind, big waves at the start of the evening and a boat that tries to approach me is going up and down. A support diver jumps at the surface and catches all the tanks to help me to safely climb the ladder. As soon as I sit on the boat, everyone can see how tired I look. Nevertheless, they all want to congratulate the first (and only) diver on the Yamashiro.

The mood is quite good, even if all the divers have not been able to go to the bottom, this day or the next few. The team has done what they could to explore the Yamashiro. The spirit of the survivors just opened a window for us to visit the final resting place of the fallen. This window is now closed, and all divers have to respect that. There is no other explanation for all the problems that occurred during this expedition. In this trip were lost, broke or flooded:

- 1 Hammerhead Electronics for Inspiration CCR

- 1 video camera and its housing

- 1 Halcyon canister light

- 1 Poseidon regulator

- 2 anchors

- 550m of ropes

- 10 buoys and containers

- 2 dumbbells (??)

- 1 Otter dry suit

- 1 Decorider bail-out rebreather

The team also needed:

- 400kg of personal equipment

- 14 porters in various airports and ferry terminal

- 20kg of rice and chicken

- 54cans of Diet Coke and Pepsi Max

The tables used were designed by V-Planner and ANDI-GAP, with a 5/75 diluent and a progressive setpoint (1.0 on the bottom increasing up to 1.3 during deco). They were backed-up with VR3-VPM computers.

Thanks to Rob Lalumiere, Ross Hemingway, Eveline Verdier, the support divers. Congratulations to Anthony Tully for his so informative articles about the Battle of Leyte. Thanks to our sponsors: ANDI, PSAI, Golem Gear, Mermaid’s Dive Center, OMS, Otter Dry Suit, Northern Diver, Cochran, RebreatherWorld Forum. ■