No One Else Will Ever Dive Higher or Report on this Unknown Expedition.

Underwater Himalayas – these words, while absurd at first glance, began to make sense in 1999 when Andrei Andryushin (NAUI dive instructor) together with his friend and adventure companion, Denis Bakin, have been traveling in the area of Anapurna, one of Nepal’s eight-thousand-meter mountain peaks. At one of the passes, a sherpa guide told Andrei that not far from their route lay Tilicho, the the highest mountain lake in the world.

Contributed by

Different sources positioned the lake at an altitude varying from 4,960 to 5,200m above sea level and described its size as 4 by 1.5 km across. Asking the locals and guides about the lake as well as subsequent internet search confirmed that no person had ever dared to dive in the lake.

The Big Idea

As it usually is with decisive people, the path from an idea to its practical realization was not long. Upon his return to Moscow, Andrei met with Vadim Belenikin, president of Sprout Dive Club, and made a presentation of his idea – to set an unbeatable world record by making a dive in the highest mountain lake in the world. Vadim strongly supported the idea.

Soon the following group of enthusiasts started working on the project: Andrei Andryushin, Denis Bakin, Vadim Belenikin, Maxim Gresko, Pavel Ruslanov, Guennadi Slobodanyuk, Dmitri Friedman and Svetlana Chistyakova.

To everyone’s disappointment, the representative office of the Guinness Book of Records turned down the request to register the record since their representative could not participate in the expedition personally. But neither this nor the lack of sponsors and high cost of the expedition could stop the enthusiasts in their determination to set a new world diving record.

In pursuit of their dream, the adventurers decided to finance the expedition with their own personal funds. All logistics issues were handed over to the Himalayan Club, whose president, Sergei Vertelov, decided to join the expedition personally.

Challenges

The task to bring over half a ton of equipment, including a compressor, and a group of divers to a remote region of Nepal located at the same altitude of that of the peak of Elbrus, looked complicated by any standard. Another problem was the absence of proven tables that would allow divers to calculate maximum duration and depth of a dive at such an altitude.

On top of that, urgent evacuation in case of trouble was impossible, and the group could not get information on the availability of a single pressure chamber in Nepal. It’s a well-known rule that air travel should be avoided for some period after diving. But the atmospheric pressure at the altitude of the lake of Tilicho is 0.5 bar, which is much less than in a cabin of any commercial aeroplane. After some approximate calculations, it was decided that the dive depth should be limited to 25m with a maximum exposure of one minute.

Then, there was the flight to Katmandu, a transfer to a run-down local carrier, a flight to Manang — a village claiming to have the highest dirt airstrip in the world (3550m above the sea level), a two-day stopover for acclimatization, a check dive in a local lake and getting a blessing from a local lama, followed by an exhausting two-day climb to Tilicho.

Tilicho

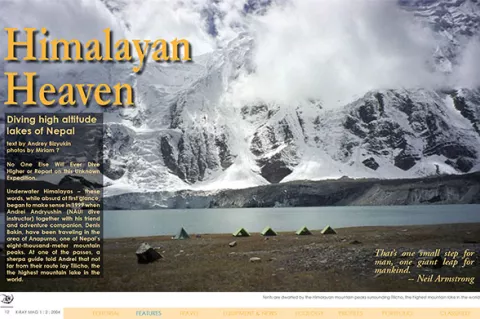

On September 23rd, 2000, the expedition reached the lake. Tilicho astounded everyone with its pristine beauty. The lake was absolute cyan in colour. On the lake surface, huge pieces of ice were floating, sparkling in the cold rays of the sun. Later, it became clear that the ice was brought to the lake by avalanches, which rushed several times a day down the glacier covering the western slope of the mountain.

The camp was set up on the shore opposite to the glacier. At the water’s edge, our GPS (global positioning system) was showing an altitude of 5,000m. Due to insufficient acclimatization period, most of the group members were suffering from different symptoms of altitude sickness (headache, nausea, etc). It was then decided to follow the initial plan and begin diving the next day.

Sunny weather that everybody enjoyed during the day was replaced by snow, strong winds and temperatures at minus 10°C during the night.

In the morning, with the help of an inflatable boat and an echo sounder, the first depth measurements were taken. The measurements showed that a narrow shallow band by the water’s edge near the camp sloped abruptly into a sharp rocky incline that was much deeper than what the echo sounder could measure (max. 75m). In addition, strange formations resembling seaweeds were found at the depth of 50m.

Preparations

With a lot of effort, a Colty Sub compressor managed to fill the air tanks up to 100 bars. But the weather started getting bad again, so the first dive was made from the shore near the camp. This dive, even though a shallow one at 10m, plus exposure to extreme temperatures during the following night, exhausted the team. The night was very cold and gusts of wind and snow tore out two tents.

On the morning of September 25th, Andrei was still willing to accomplish the goals of the initial plan. Together with Denis Bakin, Maxim Gresko and the sherpas loaded with diving equipment, he went over to the northern shore of the lake where the profile of the slope and shoreline would allow them to make the record dive.

Any movement at such altitude can make a person short of breath. It causes suffocation and requires time to regain normal breathing.

Two kilometres north of the camp, they chose a place with convenient access to the water. Friends helped Andrei to put on his gear, and then he went underwater. “I was moving down along a rocky slope. It was quite dark under the water. Visibility was no more that 1m. The water temperature at the surface was 6°C. My wrist computer switched over to dive mode as I reached the depth of 5m. That’s when it indicated zero depth," said Andrei. "I went down to 21m according to the computer. The water temperature there was 3°C.

The rocky slope kept going down, but I turned around and started going up to the surface following the slope profile. It was important to go back to where I started from under the water because swimming on the surface in full diving gear at the altitude of Elbrus peak requires inhuman effort. My dive lasted for 10 to 15 minutes and brought no surprises.

Afterwards, I felt great satisfaction that I reached my goal, and I experienced a rush of energy, probably thanks to breathing oxygen-rich air from the tank. I did not discover any forms of underwater life, but this came neither as a disappointment nor as something unexpected. But the most important thing was what we did accomplish – no one will ever dive higher than we did,” said Andrei.

On the same day, the group decided to take the road back. The world record had been set.

Breaking Records

The Russian team set the absolute record in high mountain diving. They are the first to accomplish a dive in the highest lake in the world. Of course, in setting out on this expedition, they staked a lot on pure luck. But luck favours only those who dare.

Afterthoughts

I recently asked Andrei, "Would you like to repeat that record dive after all these years?"

He replied, "Now, I think I would, but up there in the Himalayas, it was really tough. I think it’s human nature to forget the hardships and remember only the good things such as a good team and the breathtaking beauty of the mountain lake." ■

Andrey Bizyukin, PhD., makes his home in Moscow, Russia, and reports on adventures high and low throughout the world. For more information, visit his website at: https://xray-mag.com/contributors/AndreyBizyukin

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #2

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #2

- Log in to post comments