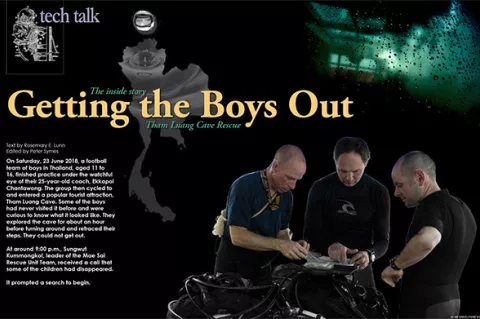

On Saturday, 23 June 2018, a football team of boys in Thailand, aged 11 to 16, finished practice under the watchful eye of their 25-year-old coach, Ekkapol Chantawong. The group then cycled to and entered a popular tourist attraction, Tham Luang Cave. Some of the boys had never visited it before and were curious to know what it looked like. They explored the cave for about an hour before turning around and retraced their steps. They could not get out. At around 9:00 p.m., Sungwut Kummongkol, leader of the Mae Sai Rescue Unit Team, received a call that some of the children had disappeared. It prompted a search to begin.

Contributed by

At 10:00 p.m., Kummongkol led the first responders into the cave. The team of 14 local rescue workers set up a light and found the boys’ bicycles and sports equipment, which had been left near the entrance to the cave.

The next day, shoes and bags were found inside the cave. However, the search was temporarily suspended because continual heavy rain thwarted access to Tham Luang cave. The rescuers could still enter the first part of the cave, but the small hole leading farther into the cave was flooded, so they went back and contacted the Sirikorn Rescue Team because they had diving equipment. A team of 22 local rescue workers and divers then entered the cave but found their diving cylinders got stuck during the dive.

“I decided to reach out to the Royal Thai Navy to send the Thai Navy SEALs to help us because they would have specialist equipment. They confirmed they would come,” said Narongsak Osottanakorn, Governor of Chaing Raid.

The Thai SEALs arrive

Twenty Royal Thai Navy SEAL divers arrived and entered Tham Luang Cave at around 2:45 a.m. on Monday, 25 June, and headed for Chamber 3 in the cave. It took them about an hour to get to the chamber.

SEAL Captain Anan Surawan told Channel NewsAsia: “After Chamber 3, there was a T-junction. One section was under two metres of water. There was a small hole in which we could dive through. On the other side, there would be a small sand bank on the right, and it was thought the kids would be there.

“A diver felt his way through with his hands in the dark. He found a hole that he could push through with his foot. The more he pushed, the further in it went. The diver emerged after diving for some time to tell us that they could get through the hole. The divers came back and told us that they did not find the kids. We were worried. Where were the boys?”

The Royal Thai Navy later posted on their Facebook page that the team had stopped diving around 1800hrs because it had been raining all day and the water level in the cave was rising. They stated, “Handprints were found around the cave wall, but we still cannot locate the children.”

A SEAL diver said that the water was so murky that even with lights, they could not see where they were going underwater, so they needed to be able to lift their heads above the water.

Anupong Paojinda, the Interior Minister, told the media that the divers could only proceed when enough water was pumped out so that there was space between the water and ceiling to make it safer to work. Pumping the water from the cave and the surrounding area would prove to be a mammoth and vital task for the agencies and volunteers.

Very brave men, but ill-equipped

It needs to be pointed out that SEAL divers across the world are specialist military personnel, trained to deal with unusual and unconventional warfare, i.e. reconnaissance missions and underwater demolition. Their training is tough and conducted in harsh and extreme environments. There will, however, be very little, if any, training done in dry and wet caves, because this is not an environment a SEAL will tend to encounter in their career. Therefore, the SEALs were not equipped nor trained for this specific rescue location—i.e. a nil-visibility overhead environment, where you cannot go up if you have a problem, and they found the caving and cave diving challenging.

The international cave diving team had nothing but the utmost respect for the Royal Thai Navy SEALs, and considered them very brave, because they were operating in such a harsh, alien situation. The rescuers discussed the situation and agreed that they needed help from experts.

British cave diving

Britain has a long history of cave rescue, with some of the teams being in existence for more than 70 years across the United Kingdom and Ireland. Caving and cave diving rescues require specific skills and equipment to safely extract injured or trapped explorers. Methods include confined space, mountaineering and rope techniques that work in a difficult and demanding environment, i.e. somewhere pitch black that is frequently muddy, cold and wet. This can include small passages and low or no-visibility conditions.

British cavers also have a long history of overseas cave exploration and surveying, and this is certainly the case in Thailand. In particular, members of the Shepton Mallet Caving Club, Mendip have helped catalogue, survey and describe a number of Thai caves over several years, including Tham Luang cave. When the news came through that the boys were trapped, the archives at the Shepton Mallet Caving Club were raided, and surveys and information on the Tham Luang Cave were sent to Thailand to help the rescuers.

The first foreign caver on the scene was also a Brit—more specifically, Vern Unsworth, an active, experienced caver of more than 40 years standing. Unsworth learned to cave whilst exploring systems in the Yorkshire Dales. In recent years, he has been extensively exploring Tham Luang Cave. Unsworth therefore splits his time between the United Kingdom and a village in Chiangrai Province, situated about 15 minutes away from the cave system. Unsworth had been involved in cave rescue operations in the United Kingdom, but “nothing on this scale.”

“Tham Luang has been my third home for the past six years,” said Unsworth. In 2014 and 2015, Unsworth was part of a British caving team that conducted further surveys of the cave. Other members included Martin Ellis, Phil Collett and Rob Harper.

On 24 June 2018, Unsworth had planned to visit the Tham Luang system to see what the water levels were like and had prepared all his equipment ready for a solo cave trip. Instead, he received an early morning phone call. Unsworth told CNN, “I got called out at 02.00 Sunday morning (24 June) saying that children were missing in Tham Luang. Can I come and help? I drove straight to the cave and I was there for the whole 17 days.”

Unsworth suggested that the boys would not have gone into a part of the cave called Monk’s Series. “It is not a very nice section of the cave,” said Unsworth. “Most people go left and head for a section called Pattaya Beach. It is a big sandbank. Once I knew the way on to the far end was blocked, then it wasn’t going to be a job for normal cavers. We needed people with diving experience.”

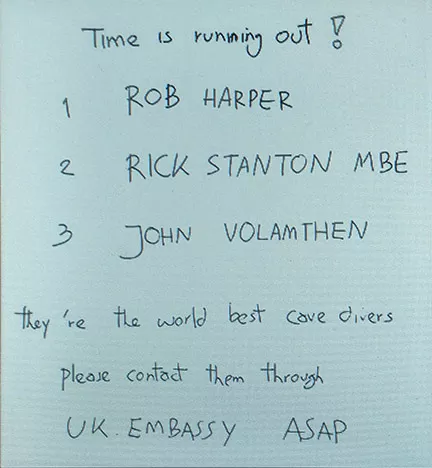

Unsworth writes a note

Unsworth understood that whilst the Thai SEALs were doing their very best, they were not used to diving in water the colour of strong, black coffee. He knew that specialist cave diving expertise would be urgently needed at Tham Luang Cave. The conditions were pretty much identical to British cave sump diving—a constricted, low or no-visibility, flooded environment. It was important to get the experience there to support the Thai Navy SEALs. Unsworth told CNN, “It was a race against time. They needed world-class divers, and that’s what we have got.”

On Tuesday, 26 June 2018, Unsworth handed a note to Weerasak Kowsurat, Thailand’s Minister of Tourism and Sports (Kowsurat then re-wrote the note in his own handwriting, so there are now two notes in existence). According to Unsworth, his note to the minister said: “Time is running out! 1) Rob Harper; 2) Rick Stanton MBE; 3) John [sic] Volamthen—they’re the world’s best cave divers. Please contact them through UK Embassy ASAP.”

Later that evening, Kowsurat made a WhatsApp video call to British caver Rob Harper. This request was not unexpected because there is a small team of British extreme cave diving explorers who assist in these intense rescues.

Experienced, respected cavers

Harper is a respected caver with over four decades of experience. He has explored and surveyed caves in Somerset, Panama, Peru and Thailand. In addition, he is Cave Leader for Dan Yr Ogof Cave in South Wales (a Cave Leader has a set of specialist skills in order to safely lead others underground). Rob Harper has done a lot of caving in Thailand. In fact, he had only just returned from a caving trip in the country when he got the phone call that he was needed.

A British caver told me: “Rob would only say he was doing what any caver would do in that situation. No drama. No fuss. Just get on with it. Rob is cool, calm and collected—the one to have on your side in a crisis.”

Stanton and Volanthen are experts in low-visibility cave dives within small passages. “Rick is the quiet man who quietly and continuously, with incredible determination, starts at A and gets to Z, and achieves things. Nothing stands in his way. He is one of those individuals who is going to get there,” said cave explorer and author Martyn Farr.

The British Cave Rescue Council therefore co-ordinated the UK response (throughout the whole rescue) and phone calls were quickly made. Volanthen told a BBC journalist that he was at work that day when he got a telephone call. “At 3 p.m. I received a call telling me I was booked on the evening flight to Thailand. I was told to expect the unexpected.”

Now that an official request had been made, the three men duly packed and headed for London Heathrow and boarded the 21.25 flight to Thailand. “A cave rescue is never where you want or expect it to be, nor is at the time of year that you would prefer it to be,” said Stanton.

Stanton, Volanthen and Harper arrive

“Nobody normally goes diving in a cave that is usually dry. When a cave like that floods, it is not a nice place to be. Certainly not a place for recreational exploration. We were only there because of what was going on,” said Dr Richard Harris, an anaesthesiologist and diver from South Australia involved in the rescue mission.

It was hoped that the boys and their coach were still alive, and had somehow found a dry space to shelter, that would remain clear of the rising water. The search had therefore escalated into a major military operation. Whilst Harper, Stanton and Volanthen flew to Thailand, the mainstream media reported that ongoing heavy rainfall and the flooded cave were causing difficulties for the rescuers.

The three Brits arrived at Tham Luang Cave late on Wednesday, 27 June, and inspected the cave. It was still raining. The mainstream media asked the divers for a comment. Volanthen duly obliged with one sentence, “We’ve got a job to do.”

Belgium cave diver Ben Reymenants also arrived onsite to assist with the rescue. Various articles in the mainstream media reported that, initially, the Brits had their doubts, because they felt that diving conditions were unsafe. They had therefore decided to pack their bags and leave (rescuers should never place themselves in a situation that can put them in danger). Whilst the Brits wished to help, neither Stanton nor Volanthen wanted to end the rescue mission, not diving, and then stay onsite for many weeks whilst the children inevitably died. Reymenants, however, felt it was possible to get in the water and did just that. By doing so, he convinced the Brits that diving operations, although tricky, could go ahead. The three divers got on with diving and started to lay line.

Reymenants was assisted by fellow Thailand-based technical divers Maksym Polejaka of France and Bruce Konefe of the United States. I do not know if these two got upstream of the dive base in Chamber 3. Amongst the other Thailand-based foreign divers who helped the SEALs (but not on the actual rescue dives) were Rafael and Shlomi Aroush of Israel, Fernando Raigal of Spain, and Tim Acton of the United Kingdom. I think most of these guys left the scene after the football team were found.

Just over 24 hours later at 01.00 on the 28 June, men and women from the 353rd US Special Operations Group landed in Thailand and joined the international operation. The skills of the search and rescue team were to prove useful. They were soon briefed by the Brits.

Derek Anderson, Master Sergeant, told reporter Mark Willacy that the Brits feedback was invaluable. “They were saying in cave diving you have to be able to lay line. You have to be able to have a way out, if you’re going in, and the currents right now are not manageable. We’re battling, trying to move forward.

“The rains are still falling, the flows are getting higher, the visibility is zero, the water’s cold. Let’s take a minute and come at this from a collective perspective of how we can tackle a really complex problem.”

“It’s when Rick Stanton uses the term ‘sporty’ that you want to get worried.”

— Martin Parker, AP Diving

Gnarly diving

Stanton and Volanthen would later describe the open circuit dives as “gnarly”. Between them, they have over 60 years of hardcore, extreme cave diving experience under their belts. In this instance, “gnarly” is being used in a very understated British way and can be translated into everyday language as “dire, horrendous, grim and atrocious.”

Sunday, 1 July, dawned, and there was finally a break in the weather, which allowed the rescue dive team to set up an operating base in a chamber about 700m into the cave complex. Equipment and air cylinders were bought in using a pulley system, whilst water pumps continued to drain the rising flood water. Stanton and Volanthen laid 800m of line from the Chamber 3 dive base to Sam Yaek.

The first miracle

On Monday, 2 July, Stanton and Volanthen were once again diving ever deeper into the cave, and laid 750m of line as they travelled through the system. “We had been laying a line, path finding, and we were right at the very limit of our last piece of line … we were actually under an airspace, so we could talk,” said Rick Stanton.

Procedure, not luck

“It has been mentioned by some members of the press that it was luck we found the boys. I would say that was absolutely not the case. We have a procedure for this situation. Whenever there was an air space, we would surface, we would shout, and we would also smell. In this case, we smelt the children before we saw them or heard them,” said Volanthen.

It was not surprising that Stanton and Volanthen could smell the boys. They had been trapped in the same location for nine days, and their bodies continued to function normally. There would have been a strong stink of sewage. No wonder the cave divers could smell the football team.

Brilliant! You are very strong

“They heard us. We heard them,” said Stanton. “The ledge wasn’t really as described. They were around the corner out of sight, and they started coming down the slope, one by one. As they were coming down, I was counting them—one, two, three—until I got to 13. So, when John asked, ‘How many of you are there?’ I had already counted them all in. They were all there. Until we had the fact that we had all 13, I was a little concerned. But once we got 13, that was fantastic.”

Stanton told me later that Volanthen climbed out of the water to talk to the boys. The boys were all barefoot, and they easily scampered up the muddy slope. The divers found the going a bit slippery in their welly boots. Stanton said there was a small, welcome moment of humour when a boy looked at his feet, then Stanton’s Wellington boots, and you could see the think bubble: “Why don’t you take your boots off and walk in your bare feet up this mud bank?”

“Given the volume of water that we had seen come out of the cave in the preceding couple of days, it was unbelievable that we found the boys, and they were all healthy,” said Volanthen. “We were very pleased, and we were very relieved that they were all alive. Cold was an issue. Some of the children were quite small, so we were quite concerned how well the small children would hold up.” Stanton added, “Of course, there was excitement, and relief that the children were still alive. It was unbelievable.”

In good spirits

What was also unbelievable was that the boys were in good spirits, and they still had some working flashlights. Modern batteries have long burn times, but for the coach to manage the torches so that after nine days, the team still had light, was extraordinary. Stanton handed off one of his lights to the team. It was time leave. “I made them a promise that I would come back, and we did. We came back with food runs,” said Volanthen.

Massive relief tempered with uncertainty

“Of course, I was thinking OK, this is just the start. How on earth are we going to get them out?” said Stanton. “I was already on the next stage. Great to have found them, but it was no means certain what the outcome would be.” Volanthen added, “We realised the enormity of the situation, and that’s perhaps why it took a while to get them out. I was completely confident we would see them again. Having said that, ‘alive in a cave’ and ‘alive outside a cave’ are two very different things.”

“All we could think about was how we were going to get them out.”

— Rick Stanton

The amazing news broke in the United Kingdom at approximately 16.30, that the football team had been found in a relatively small, dry air space south of Pattaya Beach. As the chimes of Big Ben died away, newscaster Alan Smith announced in quiet tones, “The authorities in Thailand say that 12 children and their football coach that have been missing in flooded caves for more than a week have been found alive.” There were a lot of confused reports and figures published such as “2.5 miles / 4 km from the entrance” because the US press did not understand metric measurements. The team was found 2,250m from the entrance of the cave.

What happened next?

At the time, I wrote, “This is a challenging rescue, and it has not been helped because it is monsoon season. The weather factor cannot be underestimated. If it stays dry and the cave system is successfully pumped clear of water, this will positively aid the rescue.”

The group could be “dived out”; however, this is a high-risk solution. It is a very long swim of 90-odd minutes and counting, in cold water, tight passageways and very poor or no visibility. A British Cave Rescue Council spokesman said, “Although water levels have dropped, the diving conditions remain difficult. Any attempt to dive the boys and their coach out will not be taken lightly because there are significant technical challenges and risks to consider.”

The team in Thailand conceived a plan to dive the boys out one-by-one, with each boy wearing a full-face mask. They liaised with the Cave Diving Group, more specifically Gavin Newman, to get things moving in the United Kingdom. Stanton said, “We opted to use positive pressure full-face masks because it was the best solution to protect the airway of the unconscious boy. We didn’t have to worry about a regulator falling out or getting dislodged from a boy’s mouth.”

Newman had a very busy few days. He sourced, co-ordinated and collected equipment from various places in the United Kingdom and got them onto short notice outbound flights to Thailand (it has to be said that Thai Airways was very supportive—this is not always the case with the airlines). Newman also delivered key members of the British rescue team to London Heathrow, and he worked with Neil Brock to problem solve for the Brits already out in Thailand.

A number of UK companies quietly supported the rescue mission from afar. Peter Wilson at Miflex opened his stock room and donated Miflex hoses, OmniSwivel fittings and quick disconnect Swage Locks. These were collected by Newman, and the stock was flown out with Jason Mallinson and Chris Jewell.

Dave Blackham of Espirit Film and Television also opened his cupboards, and Newman collected several Ocean Technology Systems Guardian full-face masks. Richard Major and Wraysbury Dive Centre became the “rescue post office”. Wraysbury received deliveries, donated every single A-clamp adaptor they could lay their hands on, and provided very necessary subsistence (mugs of tea and bacon rolls) to a tired Newman.

Prepping equipment

Meanwhile, Neil Brock of Bristol Channel Diving Services spent Thursday, 5 July, prepping the OTS Guardian full-face masks, so that they were ready to be flown out to Thailand. Twenty-four hours later, there was a change of plan because it was felt these masks would not fit a small Thai face. Newman had received a request from the Brits in Thailand that they wanted positive pressure full-face masks. Brock consequently serviced and prepped two Aga Interspiro Divator full-face masks. British police drove these to Heathrow with blue lights flashing, to make sure they made the overnight flight to Thailand.

A full-face mask does not have a traditional mouthpiece. You simply breathe in to take a breath. The majority of full-face masks are negative pressure masks; therefore, if there is a leak, the diver could also breathe in a fine spray of water. Hence, divers will not dive a negative-pressure full-face mask in polluted water, because if the mask leaks, there are potential health issues. The Aga Divator mask is a high-flow positive-pressure mask, so the gas is fed into the mask and this helps prevent the mask from leaking. The air pressure is higher than the surrounding water pressure. If the mask leaks, air leaks out, water does not leak in. This was especially important for this rescue mission.

The Brits also needed an oxygen booster pump. Brock sent his oxygen booster pump to Thailand.

It should be noted that all the above companies who donated equipment did so with the expectation that they would never see their gear again. No invoices were raised. No money changed hands. It was done to support the Brits to get the football team out alive.

Newman said mid-way through the rescue mission, “The support has been really impressive. Everyone is really pulling together and helping us with offering us any equipment that we need. Thank you.”

An “Apollo 13” moment

In April 1970, there came a moment during the Apollo 13 NASA moon mission that it was realised that the Command Module was fitted with square filters whilst the Lunar Module used round filters. These vital filters removed carbon dioxide. A ground team at NASA was charged with making a square peg fit in a round hole using only items and equipment the astronauts would have in space. NASA came up with a working solution, which was relayed to the astronauts, who were very relieved they would be able to take up breathing again.

Newman and Brock’s “Apollo 13” moment related to the full-face masks: “Just how do you make a full-face mask fit a very small Thai face?” You simply cannot just gaffer tape or cable tie one of these masks onto the head of a small child and hope it works.

Brock worked using materials and equipment he knew the Brits would have access to in Thailand. He looked at bulking out a 5mm diving hood by adding a ring of extra neoprene to make a 10mm seal. Newman knew that Interspiro produced an insert that could be put into the mask seal to make the mask fit slimmer faces, i.e. female firefighters. Between them, they liaised with Chris Jewell in Thailand so that the masks would fit the children’s faces. ■