Istanbul—a metropolis of over 15 million inhabitants—is one of the world's most populous cities, and thus, naturally, Turkey's largest and most important city, both economically and culturally. Indeed, Istanbul remains one of the oldest cities in the world. It was the capital of the Roman Empire between 330–395 AD, the Eastern Roman Empire between 395–1204 AD and between 1261–1453 AD, the Latin Empire between 1204–1261 AD, and finally the Ottoman Empire between 1453–1922 AD.

Contributed by

Factfile

Based in Istanbul, Turkey, Ateş Evirgen is a widely published and exhibited underwater photographer, instructor and author of the underwater photography books Fotoğraflarla Türkiye Deniz Balıkları and Shooting Photos Underwater.

For more information, visit the author on Facebook at: www.facebook.com/atesevirgenphotography.

The city ceased to be the Turk’s ‘capital’ with the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 by Kemal Ataturk. Yet, thanks to its rich heritage and ever-expanding population, it maintains and increases its importance with each passing day.

Istanbul has been given various names throughout the ages—names associated with different stages of the city’s history. In historical order, these are: Byzantion, Augusta Antonina, Nova Roma, Constantinople, Konstantiniyye, Islambol and Istanbul. Intriguingly, this giant metropolis is also home to a significant natural habitat.

With many of its dwellers unaware of it, spectacular natural phenomena have been continuing for millions of years around this city. Millions living here do not realize that it is located on Europe’s largest raptor migration route; thousands of birds pass through Istanbul’s skyline twice a year. With this feature, Istanbul is located on the most important bird migration route in the world. Knowledge of this by the citizens of Istanbul might indeed be the last hope for Istanbul’s gradually disappearing nature.

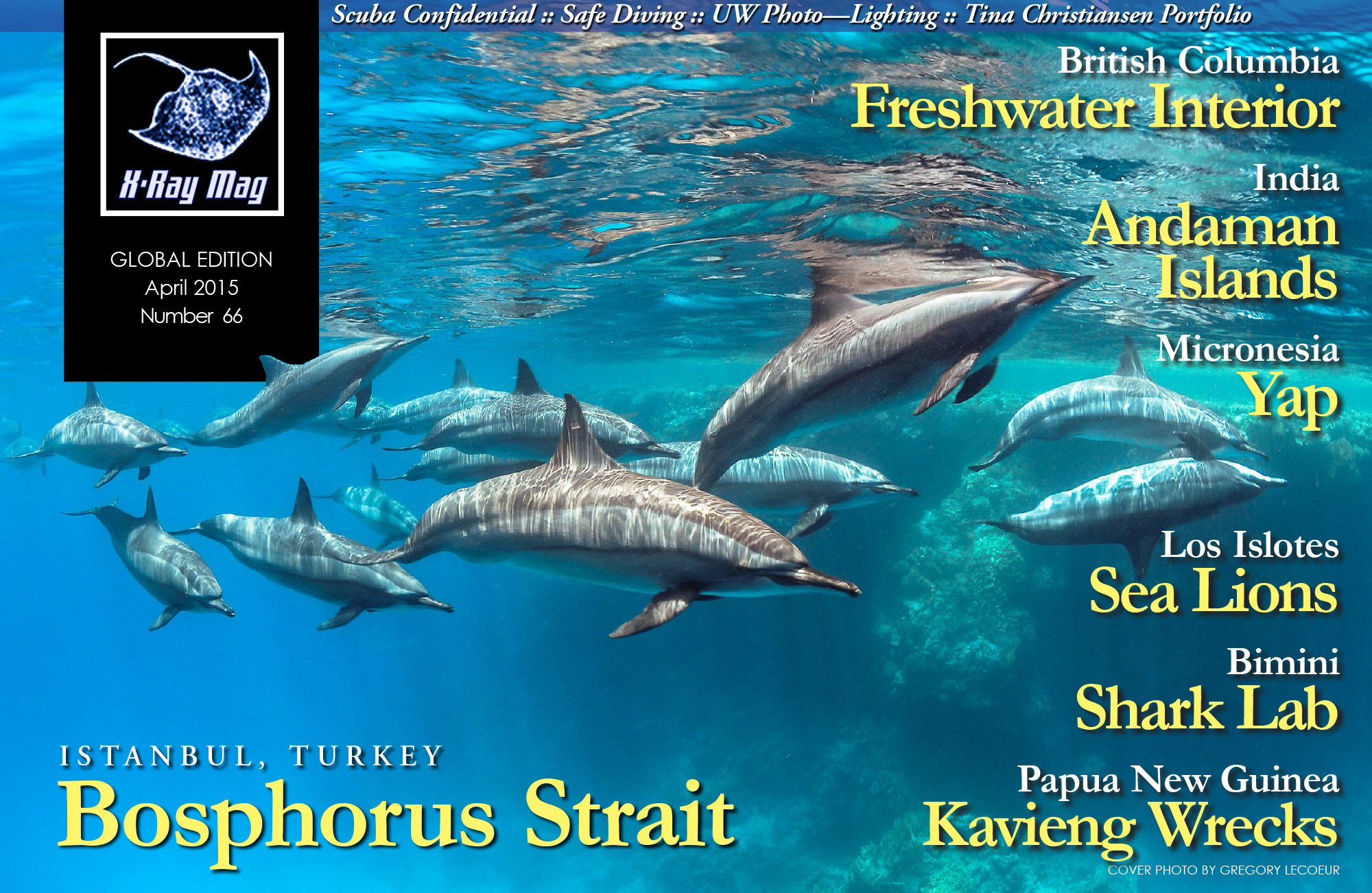

The Bosphorus Strait

But the real migration is the one of "fishes" that has been occurring periodically for thousands of years through the Bosphorus Strait, connecting the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara. In essence what gives Istanbul its true character is the strait of Bosphorus, which allows the city to rest on two continents. Indeed, this strait forms a boundary separating Asia from Europe and divides the city by name as Asian and European. It is a narrow and curved waterway approximately 30 kilometers in length; and a waterway that provides a passage for life in water.

In addition to being an ecosystem securing a delicate balance, the strait acts as an ecological tunnel regulating the two-way passing of marine organisms between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. However, few people recognize this aspect of the Bosphorus.

Indeed, fishes coming from the Mediterranean and the Aegean are forced to pass through this strait in order to be thoroughly lubricated in the waters of the Black Sea, rich with nutrients, to later ovulate. This journey makes the Istanbul Straits one of the most dynamic regions of the world for fishing. Those migrating fishes, who first lay their eggs and then thoroughly become fed when the water cools down, begin to migrate back and pass through the straits in order to return to their homes. Most famous of these fishes are the northern bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda), blue fish (Pomatomus saltator), Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus), chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus), and horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus). Hence during this journey, starting from small to big, these fishes also become bait for others. During rich times of this migration in the past, it was also common for great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), the most dreadful and famous hunters of the seas, to enter the Sea of Marmara and progress to the Bosphorus Strait, in search of shoals they pursued.

Back then, those great white sharks that got caught in fishing nets and lines were sold for money. But today, those old shoals don’t pass through these straits anymore. Overfishing and pollution have reduced the fishes in these seas, whilst premature fishing has further prevented the arrival of larger fishes who eat them. In turn, this has caused the disappearance of large tuna which live off these fishes, and subsequently of the great white sharks who track them.

Scuba divers and underwater photographers cannot be expected to remain indifferent to this, a sea life that used to host such a habitat until recently. Having said that, due to strong currents and busy sea traffic, strait coasts are not only unsuitable for scuba diving but they are moreover dangerous.

Diving

Even so, the coasts of Istanbul at the exit of the strait are busy diving locations for scuba divers. One top location is "The Princes’ Islands", close to the Anatolian side of Istanbul. These islands, also dubbed the “Istanbul Islands”, consist of nine large and small islands and two rocks near their shore. Five of them—Büyükada, Heybeliada, Burgazada, Kınalıada and Sedefadası—constitute a district of Istanbul and are still inhabited.

There is no continuous and regular settlement on the smaller islands of Sivriada, Yassıada, Kaşık Adası (Spoon Island) and Tavşan Adası (Rabbit Island). These small islands are the main dive spots for divers in Istanbul—especially Sivriada, Yassıada and Tavşan Adası, in terms of diversity, would easily compete with top dive locations in the Mediterranean.

One cannot expect not to find remains of ancient civilizations in the seas of a city that served as capital for the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires. Indeed, it is very common to come across ruins during dives. A Byzantine shipwreck of archaeological value was discovered 60 to 70 feet deep underneath the southern side of Sedef Adası (Mother of Pearl Island). Therefore, Sedef Adası remains the only island closed for recreational diving out of them all.

Marine life

A large part of Turkish coasts (including the Aegean) reveals a Mediterranean character. Therefore, organisms which could be seen in a dive off southern European shores are quite similar to organisms found in Turkey's southern coasts, in terms of water temperature, visibility and other characteristics. Yet the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea show many differences from the Mediterranean Sea by way of structure, living organisms and other factors.

As an extension of the Mediterranean Sea, the Sea of Marmara shows significantly more similarities with the North Atlantic Seas. Due to the development of international sea transport and maritime traffic, most species that do not belong to these seas, carried by ships' ballast waters, show exotic diversity of life in the Marmara. Thus there is a palpable excitement of the many divers taking photos of various sea creatures at those Istanbul coasts.

Biological life on Istanbul shores displays a great variety. However, as a result of population growth and human activity in those areas, adverse environmental conditions brought about by urban lifestyles and industrial waste have been the primary causes in the decrease of fish species in those seas.

The Sea of Marmara, transferring water between its two connecting seas through the Bosphorus, has a two-layer water system. This is vital for species living in the sea. In these circumstances, while some sensitive species disappear due to pollution, some pollution-tolerant species even manage to increase with each passing day. These species are called "gastropoda" when formed from sea slugs and sea snails, and "bivalvia" when formed by mussels, clams and alike.

It is hard to come by fish species of high commercial value off Istanbul shores. There is not much of these species to be seen, bar a few benthic, or bottom-dwelling, species. Nevertheless, these shores can be true "muck diving" zones. A wide variety of soft and solid coral species, crustaceans from different species, sea snails, sea slugs and jelly fish can be seen everywhere. In fact, the soft coral species living in benthic style, sea urchins, anemones, crustaceans and many more demersal fishes present a golden opportunity for underwater photographers eager to take closeup and macro pictures.

Conditions and visibility

Being a city of such a large population, the number of divers in Istanbul is naturally high as well. It is crucial for these divers to be able to make daily dives and take high quality photos from their backwaters, without being separated from their homes for long.

One of the challenges facing divers exploring Istanbul’s waters is the fluctuation in seawater temperature between summer and winter. Especially in winter, water temperature falls to 6°C in parallel with the Black Sea and rises to 25°C in summer. However, the temperature at the bottom water layer remains constant at 14°C throughout the summer and winter. At the junction of these different layers of water temperatures, a thermocline layer is formed. The boundary of this layer can be anywhere between 10 to 25 meters, depending on the temperature and the water.

This fluctuation in seasonal water temperatures at the Sea of Marmara affects very much the visibility as well. Alongside the cooling pace of the water, visibility in water increases even more and this enables divers to make wide-angle photographs in Istanbul’s seas. This situation continues for the whole winter. However, with the arrival of the spring months when seawaters begin to warm, visibility from up to 10-15 meters from the surface falls to 2-3 meters due to rising plankton levels. During this period, only close-up and macro shootings are feasible. At the same time, within recreational dive limits, due to the warming of the upper layer, the variety of species and populations of organisms increase.

In short, at the shores just outside of the Bosphorus, which witness one of the largest seasonal fish migrations known on earth, the nature of diving can vary significantly throughout the year. In winter, it can be very difficult to dive without a dry suit. In summer, one can easily dive with standard equipment to take underwater photos. The proximity of dive sites to the city also provides a great opportunity for urban divers and underwater photographers who want to escape the challenges of urban life and reach dive sites less than two hours after leaving their homes. This in turn renders the health of Istanbul’s seas and underwater ecosystems all the more important to scuba divers. ■