St. Croix is known for nesting leatherback sea turtles but has recently become known as one of the islands through which Hurricane Maria passed. However, life on this US Virgin Island reaches beyond the tales of these two stories.

Contributed by

Factfile

Jennifer Idol is the first woman to dive 50 U.S. states and author of An American Immersion.

She’s a PADI Ambassadiver, member of the Ocean Artists Society and has earned 29 certifications throughout her 22 years of diving.

Visit: Theunderwaterdesigner.com

REFERENCES:

Bureau of Economic Research, Office of the Governor, Charlotte Amalie. US Virgin Islands Annual Tourism Indicators. US Virgin Islands. August 2017. (http://www.usviber.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/TOUR16.pdf)

US Department of the Interior Geological Survey [map]. Virgin Islands of the United States, Office of the Governor. Frederiksted, Virgin Islands. 1958. (http://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/topo/virgin_islands/txu-oclc-20009999-frederiksted-1958.jpg)

US Fish and Wildlife Service (https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Vieques/what_we_do/science.html)

US Virgin Islands Caribbean Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment Sandy Point, Green Cay, and Buck Island National Wildlife Refuges [draft]. US Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia. August 2009. (https://www.fws.gov/southeast/planning/PDFdocuments/VirginIslandsFINALCCP/FinalCCPVirginIslandsRefugesForWeb.pdf)

St. Thomas, St. John and St. Croix comprise the US Virgin Islands on the northeastern side of the Caribbean Sea. St. Croix is isolated from the other two islands. The islands are uniquely situated next to the Puerto Rican Trench, the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, with depths exceeding 8,400m (27,559ft). This unique geography influences the nesting behavior of leatherback sea turtles on Puerto Rico and St. Croix.

Visitors since the 1400s have left their impression on the islands, seen through historic buildings and the changed landscape, especially on the island of St. Croix. The Christiansted National Historic Site reflects the activities of St. Croix’s colonial legacy as part of the Danish West Indies center for sugar production, trade, and Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Visiting peoples changed life on St. Croix, from clearcutting native tropical dry forest to prevent malaria and develop sugarcane plantations to the introduction of non-native species and export of hardwoods. Canopy loss from the removal of trees on St. Croix reduced rainfall and diminished water resources. The remaining tropical dry forest can be seen in the northwestern corner of the island and is known locally as the rainforest.

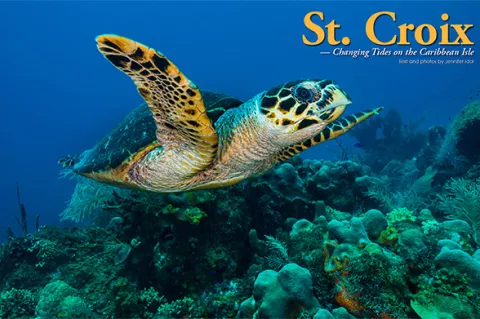

Islands are isolated and vulnerable ecological centers. St. Croix resembles a desert but is home to significant life. From four nesting species of endangered and threatened sea turtles (hawksbill, leatherback, green and loggerhead) to highly endangered least terns, the island is an overlooked gem.

Quiet oasis

Nearly all tourists visit from the United States or Puerto Rico. St. John and St. Thomas receive 90 percent of visitors to the US Virgin Islands, leaving St. Croix a quiet and uncrowded escape with opportunities to dive, snorkel or tour the island. Point Udall is the easternmost point of the United States and a gathering place to observe the sunrise. Almost three-fourths of tourists arrive by cruise boats, so the island is usually quiet.

Since food is expensive, the Plaza Extra West Superstore can be a valuable resource. The café at Sand Castle on the Beach hotel and Blue Moon in Frederiksted are restaurants for people looking for fresh food. Most tourists frequent the Christiansted Boardwalk area for pubs and food, but options are also available in the Cane Bay area.

Most goods are imported; this includes water since the groundwater faces contamination, while well-drawn water exceeds recharge rates due to the lack of rainfall. If you must have bottled water in your accommodations, buy by the gallon at the grocery store to save both plastic and money.

Hurricane Maria

Following category 5 Hurricane Irma, another category 5 hurricane moved through the Caribbean causing devastation in Puerto Rico and Dominica last October. Most of St. Croix suffered little damage, though the infrastructure struggled to provide electricity for all buildings during the first months following the hurricane.

Tornadoes caused more damage than the hurricane, creating isolated damage. Divi Carina Bay, an all-inclusive beach resort and casino, was one of the damaged businesses. They opted to rebuild a modern facility that will open in 2019. The road at Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge remains closed due to damage from the storms. Otherwise, the biggest threat from the hurricane is economic impact of travelers avoiding St. Croix due to perceptions of damage.

Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge

The southwestern tip of St. Croix was established as a national wildlife refuge when the US Fish and Wildlife Service purchased an initial 340 acres from the West Indies Investment Company in 1984. The refuge’s administration headquarters are located in Puerto Rico.

Forming the refuge caused concern about diminished accessibility to the beach. Activities are limited because the refuge closes to the public between April and August every year to protect endangered leatherback sea turtles, the largest of the sea turtles. Educational programs help the public understand why the closure is a positive activity.

Closing beaches saves lives

For more than 38 years, a program has been in place for the study of these sea turtles. Research revealed they rely on the beach at Sandy Point as a primary nesting site. Foot traffic across nests prevents successful hatching. Hatchlings emerge from their shells and wait a few centimeters (half-inch) below the sand before emerging. Stepping on a nest can easily kill 20 to 30 individuals.

Ten days before hatchlings break through the eggshell, they need more oxygen flow across the shell. Sand must not be packed down, or else nests suffocate due to the obstruction of the flow of oxygen to the eggs and hatchlings. Collapsed nests reduce gas exchange, producing higher mortality and lower success rates.

Leatherback sea turtles are extraordinarily adapted animals, even in how they lay their eggs. They lay from 60 to 80, and sometimes as many as 100 to 115 eggs. The bigger the female, the more eggs they lay. The real wonder is in the kinds of eggs they lay.

They produce both yolkless and yolked eggs. Thirty to forty percent of the eggs laid are yolkless and will not hatch. They are smaller than normal-sized eggs and come out last to form a cap over the yolked eggs. This maintains air space to optimize gas exchange as embryos develop and keeps sand from filling in. This is why keeping the beaches free of activity at Sandy Point is important.

Refuge management

The refuge is one of nine national wildlife refuges in the Caribbean. Green Cay National Wildlife Refuge was established on the northern side of St. Croix to protect the last significant populations of the critically endangered St. Croix ground lizard.

Funding for Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge has been limited since its creation. Two staff members oversee all duties of the refuge, from facilities management and safety patrol to the management of invasive species, habitat restoration and reforestation, and monitoring endangered and threatened species. Recent partnerships with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have enabled programs to continue.

Since the refuge was established, they obtained an additional 47 acres, totaling 385 acres. Depending on beach erosion, the beach fluctuates by six to 10 acres. Scientists monitor the annual erosion cycle, which threatens nesting sites and an archeological site.

The Aklis archeological site at Sandy Point has uncovered pre-Columbian skeletal material from 200 to 400 A.D. and some others that could be older. Monitoring these sites helps volunteers and interns move nests and artifacts to safety. Nest relocation saves 20,000 to 30,000 hatchlings that would have been lost to erosion.

Nesting sea turtles

For more than 18 years, Claudia Lombard, wildlife biologist and federal wildlife officer for Sandy Point and Green Cay National Wildlife Refuges, has managed and studied life at the refuge. She manages the nesting area and engages in endangered species management and population recovery.

The leatherback sea turtles she oversees are not just a keystone species, but also begin life as adorable palm-sized hatchlings. Four to six nests are usually built a day, but 2017 was an unusually quiet year for nesting activity.

Last year, Sandy Point saw the lowest number of nesting sea turtles in 25 years, with 26 individuals. Normally, 95 individuals nest at Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge during nesting season. One-fourth of the population arrived. Studying sea turtles is a long and slow process due to their slow maturation and nesting behavior.

The beach at the refuge is ideal for nesting because of sand consistency and the nearby trench. Deep water close to shore provides protection for leatherback females to ascend and quickly reach the steep beach. Leatherbacks dive deeper than all other sea turtles to depths of 914m (3,000ft) and likely to more than 1,220m (4,000ft).

Nesting females seek to lay their eggs in sand on the steep slope just over the berm. They are looking for depth in the sand to build a nest. Placement of the nest just a short distance from the water’s edge helps hatchlings escape predation and be able to reach the water.

They cannot do push-ups if they land upside down. They roll to right themselves. Their flippers are as long as their bodies, so their movement is a dragging and pushing behavior. They move slowly across sand and emerge when temperatures are cooler in the evening and night. As the temperature cools, they become vertical under the sand and push up collectively. When the sand warms, they stop moving.

NOAA marine biologist Kelly Stewart leads project leaders in leatherback monitoring and conducts hatchling DNA research with the Marine Turtle Genetics Program. Male sea turtles never return to land, so back-calculating DNA paternal fingerprints supplies groundbreaking news for population information like genetic diversity.

Males mate with females offshore, who congregate in an area as they come in to lay their eggs. A female will lay an average of 5.1 nests of eggs every 10 days. They average nesting every two years, with small numbers nesting at three- and four-year intervals. One possible reason for the interval between nesting seasons is that it takes that long to forage. Green and hawksbill sea turtles, which also nest at the refuge, lay more often than leatherback sea turtles.

If a female is disturbed when she approaches the shore, she will not lay her eggs. However, she needs to do so, or else the eggs will continue to develop additional shells, increasing mortality rates for the entire clutch. This is why it is essential never to disrupt an approaching female, and to allow her to complete her nesting behavior.

In addition to their large size, leatherbacks are highly specialized. They are an ancient remnant of early stem stock. Hard-shelled species stem from leatherback stocks. They have existed since before the dinosaurs became extinct.

Their physiology is unique. Mammals are homeotherms, meaning they maintain body temperature at consistent levels. Unlike other sea turtles, leatherbacks are facultative homeotherms that warm their blood by other methods. Heat exchangers in their circulatory system maintain core temperature. They avoid losing heat from their core to the appendages through the positioning of veins and arteries. This is believed to contribute to their deep diving ability.

They are highly specialized feeders that rely on giant deep-water jellyfish as a food source, which exists nowhere else. The diving behavior eliminates predators and competition for their food source. Most sharks live in shallow water. Their genetic evolution is steady and unchanged because they exist within an ecosystem with sectors that are relatively unchanged.

Buck Island Reef National Monument

Around Buck Island is an 8,000-year-old reef that has survived threats such as overfishing, hurricanes and white band disease, which caused a sea urchin die-off. It now faces ocean acidification, which kills coral reef structures by preventing marine invertebrates from pulling calcium from the water.

Perhaps St. Croix’s theme should be about the individuals making huge ecological impacts and serving many needs. Zandy Hillis-Starr is another of these individuals who dedicated her career to helping life on St. Croix, particularly the hawksbill sea turtles. She is the Chief of Resource Management for the National Park Service’s Christiansted National Historic Site, Buck Island Reef National Monument, and Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve. In short, she manages three national park resources with a plethora of duties.

She is the first permanent biologist studying Buck Island, and her connections with the Buck Island research lab helped produce a continuous baseline of ecological history. She was the first to document loggerheads on Buck Island and, in 2002, wrote the first protocol for monitoring sea turtles in the National Park Service.

Joel A. Tutein is superintendent of Buck Island Reef National Monument. Hillis-Starr’s love for sea turtles was cemented when Tutein showed her the first nesting sea turtle she had ever seen. Tutein feels it is an honor and privilege to work in the conservation field and strives to prevent species from becoming extinct. He knows how important people are to the survival of this ecosystem and works to connect to local youth through education.

Too many important projects are ongoing in St. Croix to enumerate, but all the studies connect life with the island. For example, Alexandra Gulick, PhD candidate at the Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research at the University of Florida, studies the relationship between seagrass ecosystem function and green sea turtle grazing dynamics and behavior. Seagrass is a necessary food source for green sea turtles, particularly in the Caribbean.

Seagrass are invaluable coastal ecosystems that not only support a diverse array of marine life, but also play an important role in carbon sequestration, protecting coastlines from storms, and buffering neighboring systems like coral reefs from nutrient runoff and pollution from coastlines.

Wildlife threats

Michael Evans, manager and federal wildlife officer of Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, has worked at the refuge for 24 years, with an additional 23 years in Puerto Rico. He manages some of the invasive species at the refuge. Mongoose were introduced in the late 1700s to remove snakes and rats. However, they eat sea turtle eggs and are an ongoing threat. Part of his work is to oversee mongoose activity.

Among his duties, he focuses on protecting visitors and teams from egg poachers and illegal activity. A number of threatening activities take place on the island, including drug and wildlife trafficking in items such as ivory and taxidermy, conducted for monetary profit.

To preserve the reef habitat, no collection of natural items is permitted in St. Croix, including sand, coral, shells, urchins and sand dollars. Customs officials confiscate these items to preserve the island. While collecting a few bits of uninhabited shells seems innocuous, the collective action of individuals has great impact. More than one ton of sand was confiscated by customs agents in St Croix from visitors in two years.

Island life

Endangered plant species depend on St. Croix. Rare trees and plants such Vahl’s boxwood (Buxus vahlii) are found only in Puerto Rico and St. Croix, and some are among the rarest trees in the world. Four species of mangrove inhabit the island: white, red, yellow and buttonwood. The St. Croix agave, or Eggers’ century plant (Agave eggersiana), is endemic to St. Croix and found only in dry regions. Night blooming cereus is a cactus flower the size of a dinner plate that opens at dusk one night each year.

West End Salt Pond is home to least terns, an endangered seabird in need of listing to better protect them. Other birds such as Zenaida doves occur on the island and are limited to the Caribbean region. Merlins and peregrines also hunt here.

Land crabs have declined in Puerto Rico and are present in St. Croix, though numbers there are unstudied. Cardisoma guanhumi are the species of land crabs found on St. Croix. Locals hunt them at night and keep them alive, feeding them for several days to clear pollution from their bodies before eating them.

St. Croix has seen an increase in shark activity. In fact, reef sharks were plentiful at the bottom of walls on all dives. While the reef life was fascinating and hawksbill sea turtles were engaging, sharks steal the show on deeper dives.

Rebuilding the reef system

The Nature Conservancy developed a Coral Nurseries and Restoration project led by Dive Safety Officer Lisa Terry. She and her team of volunteers cultivate, harvest and plant staghorn and elkhorn corals around St. Croix.

According to the Nature Conservancy, critically endangered staghorn and elkhorn coral have declined by 90 to 95 percent. Populations of elkhorn coral in the US Virgin Islands alone has dropped from 85 percent to 5 percent.

Restoration efforts are rebuilding the reefs through in-water nurseries that are strategically planted in areas where natural and human threats are low.

How you can help

Visit St. Croix to support the economy and practice sustainable behavior at home and abroad by avoiding single-use plastics such as straws and plastic bags. Leave natural life in place in this paradise by not purchasing or collecting shells, sand and coral. Place all trash in proper bins and recycle whenever possible. Share your love for this island oasis through your stories and photos.

While fish and wildlife service management needs volunteers and interns, the turtle team is limited to interns studying sea turtles with compelling sea turtle conservation goals. Participants in nest watching and monitoring require significant training and must be capable of walking in sand several miles each day or night. The turtle team is composed of six interns who work four months of the year.

The turtle watch program includes a public education opportunity on scheduled nights. These groups may observe hatching nests after participating in an educational seminar. The program is worth visiting as staff answer any questions about the sea turtles.

Life in St. Croix is a complex and changing ecosystem driven by the relationship between inhabitants, visitors, wildlife and plant life. ■

Special thanks go to the staff of Cane Bay Dive Shop (canebayscuba.com) for their support, making numerous dive sites accessible and collaborating with the wildlife refuges and The Nature Conservancy.