You won’t find Spiny dogfish on most shark diver’s ‘bucket lists’. In fact, the only time that your average diver will come into contact with a dogfish is when it is covered in batter, served with chips and bathed in an artery-constricting amount of salt and vinegar.

Contributed by

Whale sharks for example, are interesting in a Goodyear Blimp kind of way, but they really don’t do much other than swim monotonously forward, mouth agape, consuming copious amounts of plankton. If you’ve ever swum with one, you’ll be familiar with their nonchalant stare and slowly weaving tail that quickly leaves you floundering in its wake.

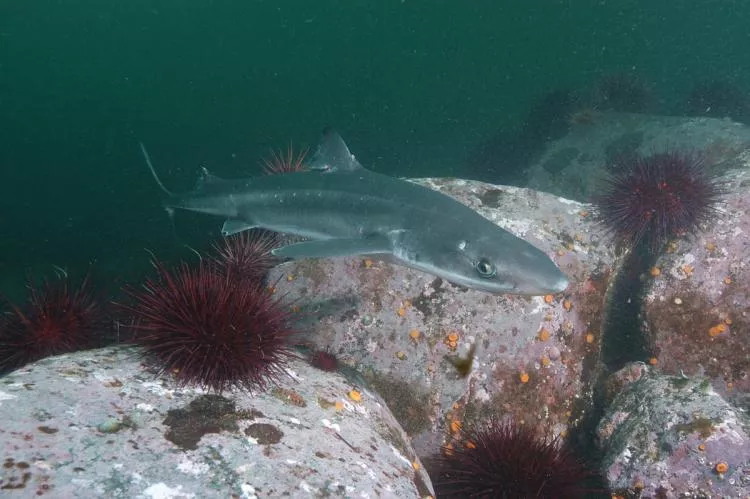

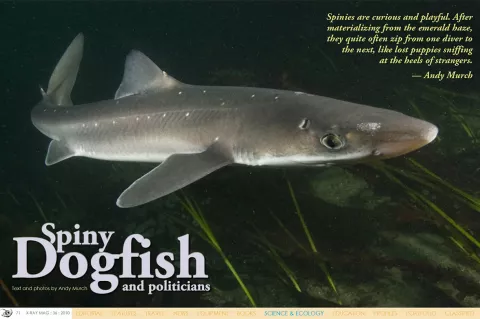

Not so with spiny dogfishes. Spinies are curious and playful. After materializing from the emerald haze, they quite often zip from one diver to the next, like lost puppies sniffing at the heels of strangers.

If you bring them a few tidbits, they’ll be your friends for as long as the food supply lasts. If not, once they have sated their curiosity, they generally disappear back into the fog, but their vibrant personalities are guaranteed to leave an indelible impression even after a very brief encounter.

Physiology

Spiny dogfish are physiologically rather special. By counting the lines on their dorsal spines (a bit like counting tree rings), scientists have calculated that they are extremely long-lived sharks, possibly reaching the ripe old age of 70. They also hold the record for the longest gestation of any living vertebrate (up to a whopping two years), and they do not reach sexual maturity until their late teens or early twenties.

Unfortunately, their slow biological clocks leave them extremely vulnerable to overfishing. Off the coast of Europe, where spinies have been relentlessly fished to supply the demand for fish and chips, populations are at an all time low.

Conversely, in the Eastern Atlantic, catch limits that were introduced a decade ago have resulted in an upswing in dogfish numbers along the eastern seaboard. Their stocks have rebounded to the point where there are reports of marauding plagues of spiny dogfish destroying nets and depleting other fish and invertebrate species that fishermen are trying to target.

In an ideal world, big schools of dogfish should not be a problem. Historically, spinies have always been abundant sharks. Veteran divers that were active in British Columbia back in the 70’s and early 80’s, relate tales of impenetrable clouds of dogfish tumbling over each other as they swept along the reefs in search of food. Their collective biomass would block out the sun, and their movements over the sea floor would generate a sand storm that reduced visibility to zero.

Population

Unfortunately, in the brave new world of the 21st century where practically all fish stocks have been depleted, the oceans may no longer be able to support dogfish in such large numbers.

The wholesale slaughter of larger shark species is a big part of the puzzle. Overfishing of apex predatory sharks has left spinies with few natural enemies that are capable of keeping their numbers in check.

With many fisheries hanging in the balance, more and more fishermen are expressing that western Atlantic dogfish stocks should be culled to take them out of the fight for food.

Last month, spiny dogfish were among eight species of sharks that were put forward for inclusion in CITES Appendix II. A CITES listing would have given the endangered European spiny stocks a much needed respite from fishing pressure, but it would also have protected the rampant Western Atlantic populations.

Through a combination of questionable science and political maneuvering by wealthy fishing nations, all of the proposed species were rejected. It was a big blow to shark conservation in general, but regarding spinies, perhaps that was a good thing.

Solutions

The sensible course of action would be for the European Community to impose a regional moratorium that would protect European dogfish stocks while allowing North American fishing fleets to keep operating. Hopefully, this will occur in the not too distant future.

Meanwhile, the coast of British Columbia is still one of the best places on the planet to encounter friendly spiny dogfish. Quadra Island—which has some of the most vibrant wall diving in the Pacific North West—is a particularly dogfishy place. During the summer months, it is fairly common for divers to be buzzed multiple times on a single dive. If you’re not the type of diver that is scared off by ‘non-tropical’ conditions, give BC a try. A dive with a handful of spiny dogfish is an experience you’ll not soon forget. ■