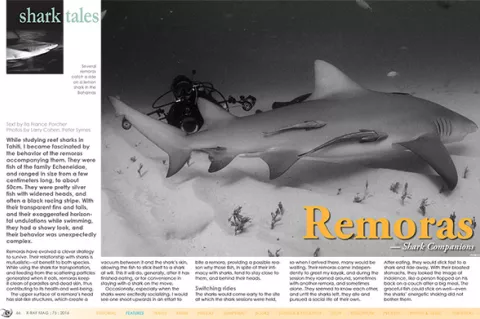

While studying reef sharks in Tahiti, I became fascinated by the behavior of the remoras accompanying them. They were fish of the <i>Echeneidae</i> family, and ranged in size from a few centimeters to about 50cm long. They were pretty silver fish with widened heads, and often a black racing stripe. With their transparent fins and tails, and their exaggerated horizontal undulations while swimming, they had a showy look, and their behavior was unexpectedly complex.

Contributed by

Factfile

Ila France Porcher, author of The Shark Sessions, is an ethologist who focused on the study of reef sharks after she moved to Tahiti in 1995.

Her observations, which are the first of their kind, have yielded valuable details about their lives, including their reproductive cycle, social biology, population structure, daily behavior patterns, roaming tendencies and cognitive abilities.

Her next book, On the Ethology of Reef Sharks, will soon be released.

Remoras have evolved a clever strategy to survive. Their relationship with sharks is mutualistic: of benefit to both species. While using the shark for transportation, and feeding from the scattering particles generated when it eats, remoras keep it clean of parasites and dead skin, thus contributing to its health and well-being.

The upper surface of a remora’s head has slat-like structures, which create a vacuum between it and the shark’s skin, allowing the fish to stick itself to a shark at will. This it will do, generally, after it has finished eating, or for convenience in staying with a shark on the move.

Occasionally, especially when the sharks were excitedly socializing, I would see one shoot upwards in an effort to bite a remora, providing a possible reason why those fish, in spite of their intimacy with sharks, tend to stay close to them, and behind their heads.

Switching rides

The sharks would come early to the site at which the shark sessions were held, so when I arrived there, many would be waiting. Their remoras came independently to greet my kayak, and during the session they roamed around, sometimes with another remora, and sometimes alone. They seemed to know each other, and until the sharks left, they ate and pursued a social life of their own.

After eating, they would stick fast to a shark and ride away. With their bloated stomachs, they looked the image of indolence, like a person flopped on his back on a couch after a big meal. The graceful fish could stick on well—even the sharks’ energetic shaking did not bother them.

They seemed to be capable animals—able to function independently of sharks when necessary. They were likely able to find a shark whenever they wanted to if, for some reason, they lost their usual host.

At one of the sessions, a large shark who rarely visited glided in. As she swept through the site, a remora with a full stomach who had been sticking to one of the large nurse sharks, switched to her as she passed, and left with her sometime later. A lull ensued, after which more sharks began to drift in from down-current. One was another elderly female visitor, and the stuffed remora, who had left 15 minutes before, was reclining on her head, looking just as stupefied as before!

Evidently, in the interim, the two shark visitors had passed close enough to each other for the remora to have changed sharks, like a person changing planes.

Displaying preferences

This and other similar observations, suggested that remoras distinguish between individual sharks and have preferences. Perhaps a remora who usually remained with the same shark would learn its habits, and adjust its lifestyle accordingly, rather than being subject to continual surprises and unwelcome displacements with strange sharks. Certain remoras remembered me over long spans of time, and they appeared to know individual sharks too. In spite of their lethargic appearance, they were alert and making decisions flexibly according to the situation.

Early in my study, a remora arrived with a group of sharks that had just come to the lagoon from the ocean. He was attached to the chin of a female shark who kept trying to dislodge him. When she succeeded, he flew first after one shark, then another, yet did not join any of them. When they left, he came flitting back to where some fish scraps lay, and there he waited, moving around in apparent agitation. Every so often, he swam a few meters in one direction, returned, and after a while, took a similar foray the opposite way. Time passed while we waited for the sharks to return.

When at last a shark appeared, scarcely within visual range, the remora saw it and went winging after it, his fins a blur. But he did not catch up to the shark, and soon returned to roam around in my vicinity, sometimes going away in one direction or another to look more widely.

Eventually, he came tentatively over to me, and flowed up my leg and around my body, trying to stay out of sight as I bent to stroke him. I fed him some crumbs from a scrap, and he eagerly ate until he was full. Then he settled on my leg and eventually attached himself while I roamed around looking into the coral crevices. After half an hour, when no sharks had returned, I tore up a fish head in hopes of attracting some back for him, and left.

It was not the only time that a remora appeared to become distressed due to losing his shark. In general, each fish seemed to remain aware of the movements of the shark with whom he had come, in order to be ready to leave with it.

Each remora was different. Some seemed to consider me a welcome companion right away, while others would not come near.

Polite companion

One evening after a shark session, I was feeding the fish when an exceptionally large, white remora arrived with a group of visiting blacktips. I was shredding meat from a fish head, and he put his head deep down inside, and grabbed bites beside my fingers. I was concerned about accidental bites, but he behaved as if he was used to eating with a person with skin the color of the meat, and never made a mistake. Soon, he was stuffed. Once, he was attracted away by one of the young sharks, who was circling nearby close to the surface, but he quickly left her, returned to me, and rejoined the same visiting shark with whom he had arrived, the next time she passed.

He reappeared about a month later when it was nearly too dark to see, and remembered me. He flitted back and forth in front of my mask, then around my neck and torso. I had nothing at hand, however, and ignored him at first, but after a few minutes, when he went to try to get a few crumbs from a nurse shark, I searched out a fish head that still had meat in it.

I went down to the nurse shark to get the remora’s attention. When he saw me, he rose with me to the surface, and ate with his head beside my fingers as before. When the fish head was empty, I put the anchor in the boat and, holding it, began to drift away, but the remora was still curvetting around my body, so I got back into the boat to avoid displacing him. Nevertheless, he remained with the kayak, his long graceful tail waving slowly out from beneath it each time he turned. Eventually, I paddled back to the site of the sessions, where sharks were still passing in the black waters, and he left the boat.

One morning after an observation session, I had just returned to my kayak, when a remora came swimming quickly along in mid-water as if it was going somewhere. It briefly considered me, then swam on. Wondering where its shark was, I followed it at first, then turned back, and it followed. Back at the kayak, the shark soon appeared, and the remora fluttered over her body. The shark was covered with mating wounds, so I swam with her as she glided languidly away through the coral, the remora settling between her ventral fins.

Every few minutes, it swam halfway to me, then returned to her. From time to time, it fluttered off to investigate something in the area, but soon rejoined the meandering shark, wriggling over her back before taking up its preferred position between her pectoral fins. When we returned, it flew ahead to the kayak, and was flittering around its hull when we came into view. It was busy and alert, and reminded me of a dog out for a walk with its owners. Its behavior was typical of the remoras that accompanied me with a shark.

Over the years of the study, it was evident that individual remoras knew me from the sessions, and would leave their sharks to stick to me for long periods if they met me elsewhere in the lagoon, in spite of intermittent reappearances by the sharks. They had evidently learned that I was a good source of food, in spite of not being a shark. It is likely they would also accompany other species too, if an appropriate opportunity arose. ■