As Evelyn Bartram Dudas’s Nikonos III made its way toward the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean one day not too long ago, she did the only thing that made sense to her at the time. She dove after it, retrieving the camera just before it was lost amidst the twisted remains of a shipwreck on the sea floor. Her rapid descent cost her a broken eardrum. It wasn’t the first time this veteran West Chester, Pennsylvania, diver, dive shop owner, and mother of four had suffered at the hands of the sea.

Contributed by

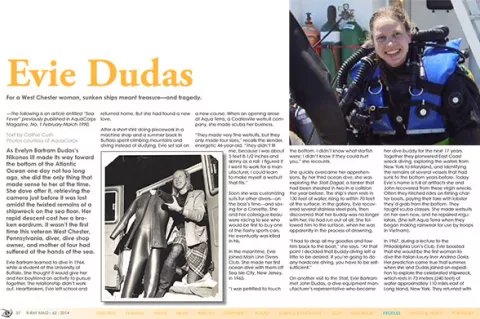

The following is an article entitled “Sea Fever” previously published in AquaCorps Magazine, No. 1 February-March 1990.

While a student at the University of Buffalo. She thought it would give her and her boyfriend an activity to pursue together. The relationship didn’t work out. Heartbroken, Evie left school and returned home. But she had found a new love.

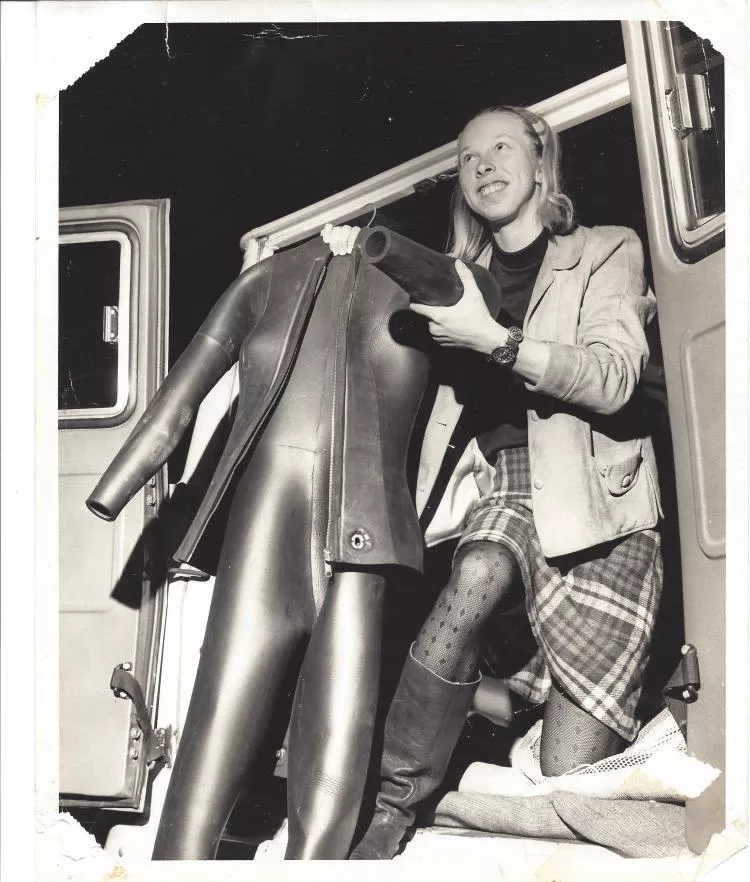

After a short stint doing piecework in a machine shop and a summer back in Buffalo spent climbing mountains and diving instead of studying, Evie set sail on a new course. When an opening arose at Aqua Terra, a Coatesville wetsuit company, she made scuba her business.

“They made very fine wetsuits, but they only made four sizes,” recalls the slender, energetic 44-year-old. “They didn’t fit me, because I was about 5 feet 8-1/2 inches and skinny as a rail. I figured if I went to work for a manufacturer, I could learn to make myself a wetsuit that fits.”

Soon she was customizing suits for other divers—on the boss’s time—and saving for a Corvette. She and her colleague beau were racing to see who would be first to buy one of the flashy sports cars. He eventually was killed in his.

In the meantime, Evie joined Main Line Divers Club. She made her first ocean dive with them off Sea Isle City, New Jersey, in 1965.

“I was petrified to touch the bottom. I didn’t know what starfish were; I didn’t know if they could hurt you,” she recounts.

She quickly overcame her apprehensions. By her third ocean dive, she was exploring the Stolt Dagali, a tanker that had been sheared in two in a collision the year before. The ship’s stern rests in 130 feet of water, rising to within 70 feet of the surface. In the gallery, Evie recovered several stainless steel pots, then discovered that her buddy was no longer with her. He had run out of air. She followed him to the surface, when he was apparently in the process of drowning.

I had to drop all my goodies and tow him back to the boat. At that point I decided that buddy-diving left a little to be desired. If you’re going to do any hardcore diving, you have to be self-sufficient.

On another visit to the Stolt, Evie Bartram met John Dudas, a dive equipment manufacturer’s representative who became her dive buddy for the next 17 years. Together they pioneered East Coast wreck diving, exploring the waters from New York to Maryland, and identifying the remains of several vessels that had sunk to the bottom years before. Today Evie’s home is full of artifacts she and John recovered from these virgin wrecks. Often they hitched rides on fishing charter boats, paying their fare with lobster they’d grab from the bottom. They taught scuba classes. She made wetsuits on her own now, and he repaired regulators. (She left Aqua Terra when they began making rainwear for use by troops in Vietnam).

In 1967, during a lecture to the Philadelphia Lion’s Club, Evie boasted that she would be the first woman to dive the Italian luxury liner Andrea Doria. Her prediction came true that summer, when she and Dudas joined an expedition to explore the celebrated shipwreck, which rests in 73 metres (240 feet) of water approximately 110 miles east of Long Island, New York. They returned with the compass and binnacle cover, a light fixture from over the wheelhouse chart table and a door handle. Dudas also recovered a porthole from the captain’s room. Their 60-metre (200-foot) plus dive takes on a new dimension of drama when Evie explains matter-of-factly that the adventure was undertaken with the benefit of gauges to monitor tank air pressure and sans other safety equipment that today’s divers take for granted.

Bent

In January 1968, tragedy struck when the pair took a Freeport, New York, fishing boat to a wreck known as the Virginia. It lay in deep water—50 metres (165 feet)—so a short dive was planned. After ten minutes the divers surfaced and swam to the ship’s anchor line, down which they would descend to three metres (10 feet) to recompress—a technique that was common at the time. As Evie pulled herself down the line, her hands lost their strength and went numb. She was bent.

“My hands refused to grip; my feet refused to kick,” she says. “I was becoming paralyzed. They rolled me on my back and I thought, ‘if this is what it’s like to die, this is not bad.’ Then I just went unconscious.”

John Dudas went at her side and helped drag her back to the boat. Divers and crew fought heavy seas to pull her back on board, finally tying a rope around her waist and hoisting her up like a doll. She recalls lying in the wheelhouse wrapped in a blanket.

“I remember the suction of the mask being pulled off my face,” she says. “I had vertigo, and I couldn’t talk or see. I tried to scream, and I couldn’t. And I remember being cold and hungry. It was a six-hour trip back to port.”

That night she was taken to the hyperbaric chamber at Mt. Sinai Hospital, where her decompression sickness could be treated. The next morning, she found Dudas at her side, crying.

“That’s when I figured out he cared about me,” she adds softly.

That’s when I figured out he cared about me.

After ten days the paralysis was gone, but it took a year and a half before the numbness in her arms and the vertigo left completely. In recent years she has had post-diving bouts of vertigo and skin bends that last for hours. Still, she continues her ‘hard-core’ diving and shrugs at the mention of the risks she is taking.

“There’s risk involved just driving to the boat,” she reminds a visitor pragmatically.