Not all artificial reefs are shipwrecks or scuttled vessels, tanks or planes. Now divers can enjoy artificial reefs growing on original sculptures mounted underwater. Jason Taylor, a sculptor from England, recently finished a photo-documentation of his underwater sculpture project in Grenada. X-RAY MAG caught up with Taylor to find out how and why he did it.

Contributed by

Taylor studied sculpture and painting in London, but he was always fascinated with creating pieces on-site in the environment. He said that he never created works for viewing inside a gallery. His sculptures were site-specific, meaning that they were created specifically for the site in which it would be viewed, such as town squares, bridges, plazas, etc. This work is equally important to Taylor.

He grew up in Malaysia, and every day after school, he went snorkelling. At age 12-13, he made a big adjustment and switched to graffiti art, leaving his mark on various urban surfaces under bridges and on trains. By age 18, graffiti art had lost its lustre for Taylor, but he still views this phase as an important one of his development as an artist.

Now, Taylor works in cement or any material he can get his hands on. All of Taylor’s work in Grenada was made from local resources since conventional materials were too expensive because they had to be imported. In Grenada, Taylor turned to local materials such as bamboo. Taylor started sculptural work as an art project in school. He did a series of workshops in casting and sculpting. But at that point, he was not diving. Later, he got his diver’s certification and decided to marry the to two great loves of his life, diving and sculpture.

Why did he create his underwater sculpture in Grenada? Well, he lived and worked there for some time as a dive instructor, getting to know the place and the people and allowing them to get to know him before he started working on his underwater art. Taylor funded the project himself and did most of the construction on the project as well. At first, people thought he was crazy. Taylor explains, “Why was this white guy spending all his money on concrete and then submerging it underwater?” Later, when divers started visiting the site and it became a standard stop for dive and tourist boats, people saw the value of the project in terms of tourism and management of the local reef.

The creative process

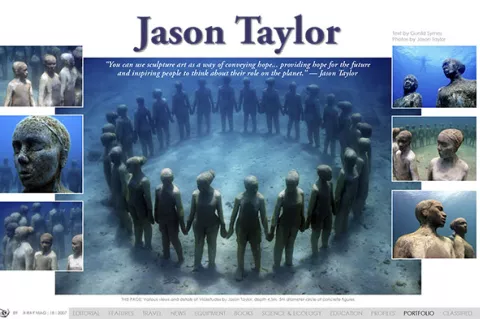

Taylor says that his creative process is different every time. “I don’t do a drawing. I just think it through and make a clay model… a mock-up of what to do. Then, I cast the forms,” he said. In Vissitudes, casts were taken of the local children along the coast. Then, Taylor filled the casts with fibreglass and silicone and worked each piece out of these materials. Then, he had to figure out how the sculpture should be connected to the seafloor. Some of best ways to do this, he said, is by mounting metal pins into the rock face, but “it’s too expensive”.

So, he had to find places in the gully which were not facing the tidal surge and currents. A big part of the foundation was made of oil drums as base plates, he said. The current had to be able to go through the sculptures because just the force of the current put so much pressure on the feet and ankles of the figures that they would break.

Taylor had to find a way to allow the current to pass through the sculpture, which was a good thing for filter-feeding organisms that later adhered to the forms. There were several design considerations. Taylor said, “I spend a lot of time on that. How am I going to get the sculpture into the dive boat, without breaking it or the boat?” Cranes to lift the sculptures were available, but it cost US$1000 to use the dive boat and the crane.

Taylor said that he found the planning and the creation of the underwater sculpture park really stressful. He said, “It was not like I was relaxing on an island paradise everyday.” But he did get a lot of help from friends. At first, Taylor worked independently. His said that he usually does not run around much in artistic circles, even though a lot of his family members are artists, just not sculptors. But he said that there were a couple artists who wanted to get involved.

He had to design and divide the sculptures into pieces, because he could not afford to hire a vessel with a crane. Hence, there were a lot of pieces to transport separately. The project took three months on land to build and one week underwater to install. Taylor had a team of three divers installing the pieces during two 2-hour dives. The sculptures lie at a depth of about five meters. Taylor said that an initial survey of the site found that it was not quite flat. So, before installation could begin, the gradient had to be fixed.

Before the project could get off the ground and into the water, Taylor drew up some technical drawings, GPS location, and permission from the local government as well as submit an application to the fisheries department, who, Taylor admitted, did think it was ”a bit weird”. Taylor chose a site that was already really desiccated, a place that he could not damage very much more than it was already. In the area, there were a couple of bays full of charter boats. The heavy use of the bays led to a rapid deterioration of the reef, he said.

Taylor had to construct the sculpture so it would last and evolve into a true reef, so he wanted to use metals. But that required sponsorship. He said, “It gets lots more expensive from there.” So, he turned to cement. Taylor actually took a course with the Reefball Foundation, to learn about the cement balls with holes used to develop new reefs. “It was very complicated,” said Taylor. “The cement you use has to have the right pH.” Now, Taylor actually places coral into his structures, embedding coral into the sculptures for propagation purposes ...

Taylor explains, “In the skeletal figure, the coral shapes the body—staghorn and elkhorn coral, which grows about two inches per year.” Taylor documented the changes to the sculpture park over time. “It really makes things more eternal even though the sculpture, such as the big tall woman, will be gone in only 15-20 years.” To keep it longer requires a maintenance program from local dive centres, he said.

Response

The response to the project was mixed. A lot of the locals could not see the reason why someone would want to build such a thing and not even get paid for it, said Taylor. Many locals linked the sculptural figures to slavery because the local history involved slavery. Taylor was surprised by this since he certainly did not have that issue in mind in the creation of the work. “I was just making sculptures of different kids holding hands,” he said.

Taylor said that he had a hard time getting into the routine of life down there. “They thought it was crazy that somebody used all his money to put concrete in the sea,” he said. “They are coming around now.” Dive boats have their own chartering system, and it is only a five-minute ride to the sculpture park, so now they come and include it as a stop on a dive trip.

Taylor said that he received so many emails from all around the world—Uzbekistan, Russia, Bali and some inquiries from the U.S. and Europe. People responded to the press coverage of the sculpture park and the photographs of the sculptures, which Taylor posted on his website. They like the work, he said, and the response has been fairly positive from environmentalists, too.

Taylor’s sculpture park was big news in England, he said. He hopes to do another park in Europe in the Mediterranean Sea. The visibility is better in cold waters, he said. And there are plenty of soft and hard coral species to populate the sculptures.

“I have worked in Australia, the Red Sea and Asia,” said Taylor, “I like to work anywhere that has better visibility. It makes the photography of the sculptures easier.”

Subject matter & symbolism

Taylor tries to do sculptures of easily identifiable objects so people can see a scene opposite of what one would usually find underwater. “Notice that I do no fishes or mermaids. I want to create a contrasting world.

The guy at a desk is surreal. There’s a peacefulness about the figure enhanced by the diving experience.”

The sculpture park lies in shallow waters, about 1.5 meters. The point of the park is to make something artistic in the underwater world, said Taylor. People in Grenada are not rich, he said, so accessibility of the park was important to allow the local people to be able to see it, too. “Usually, locals don’t look underwater,” he said, “They just fish.”

One of the sculptures depicts the Devil Woman, a powerful mythical character in Grenada, said Taylor. She runs around at night and steels children, so locals have mixed emotions about the work, he said.

What is this all about, you ask? “It’s about change… how your surroundings affect your being. Children are meant to echo their environment. The influence is determined by the physical being... their surroundings. It would be nice to cross that link,” said Taylor.

Future plans

Taylor wants to design other sculpture parks. In real time, he works in London as a freelance stage and set designer. In dream time, he wants to do a lot more diving and go abroad, of course, but finds that marketing to raise the funds is very time-consuming. In the meantime, he installs exhibitions. “I am trying to wind down and do more artificial reefs. But the making of them is stressful.” So he turned to cement.

Taylor has learned to be an underwater photographer using a small compact digital camera, in order to document his underwater works. Taylor said, “I find it really important to get into the ocean.” He wants to do a series documenting the life he sees growing in and around the sculptures such as colonies of invertebrates, octopus, a green moray eel in the dress of the woman, fish living in the desk and in the drawers of the desk. The sculptures seem hard and static, but the marine life living in them is not, he said.

Future processes

In the future, Taylor wants to produce the structures for sculptures in London and then transport them to the site. “Then, all I have to do is cast the cement,” he said. “The reef ball is a very clever design. You cast cement around the ball and then deflate the ball leaving the cement form.”

Taylor said, “It is amazing to start an idea, something small, and then realize how it evolves.” Say, an artist wants to put something underwater. Then, you need an engineer to work out how to do this, he said. “Then, you need an underwater photographer to document it.”

Taylor does not aim for new venues for his work or to exhibit in galleries. “For me, it’s all about the future,” he said, “I have some great ideas I want to try. For instance, I would like to incorporate a shipwreck into an underwater sculpture park, and make it look like a Noah’s ark with figures around it.” Taylor wants to challange the use of materials and work modern materials in a way that makes them look like part of an archeological dig, combining glass into sculptures so one can see through the piece and light can shine through the work. He said, he wants to build a Sushi restaurant underwater with living fish moving through it.

“There are a lot of subtleties of life with cement… a lot of development goes on. It’s not always resolute. I have a vague idea of what I want to try to achieve. I wanted to do a really abstract symbol, and started looking at a man sitting on a chair and reading, watching tv and drinking coffee at a table. The still life is about moments in time.” Taylor wants to allow the sculptures to be part of creating a vibrant varied habitat. “I am not into cleaning the sculptures or bringing them back up to the surface for maintenance. Eventually, they will disappear.”

For more information, please visit: www.underwatersculpture.com ■