Fossil bed in national forest in Nevada may have been breeding ground for ichthyosaurs

A study suggests that a fossil bed containing many 50-foot-long ichthyosaurs may have been a breeding ground.

In the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest in Nevada, there is a fossil bed in which many ichthyosaurs (Shonisaurus popularis) have been found petrified in stone.

Over the years, there has been speculation that they had perished in a mass stranding incident or due to a nearby algal bloom. While these were possible, there had not been strong evidence to support these theories.

Recently, researchers have presented a plausible explanation on how at least 37 of the ichthyosaurs had perished there: “We present evidence that these ichthyosaurs died here in large numbers because they were migrating to this area to give birth for many generations across hundreds of thousands of years,” said co-author and Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History curator Nicholas Pyenson, referring to a paper published in the Current Biology journal.

Figuring out the clues

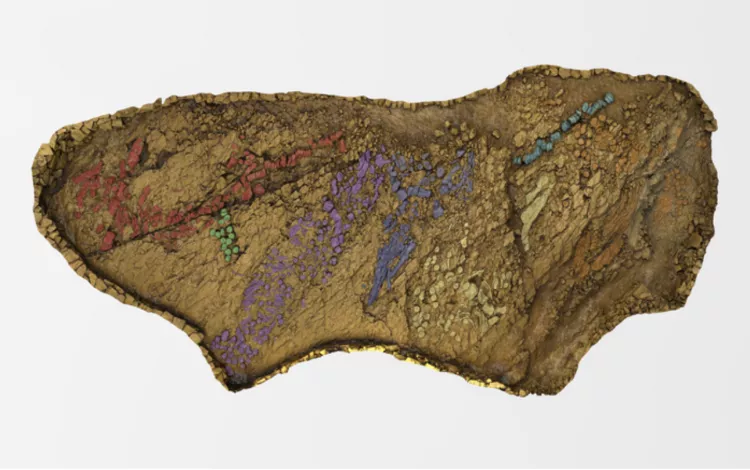

Research was conducted using new paleontological techniques like 3D scanning and geochemistry together with traditional methods like sample analysis and archival searches for photographs, maps, field notes and museum collections.

According to the geologic evidence, when the ichthyosaurs died, their bones sank to the bottom of the sea, rather than along a shoreline that was shallow enough to suggest stranding.

The area had many adult Shonisaurus specimens, as well as the tiny remains of embryonic and newborn Shonisaurus, but no juveniles. The fossil bed did not have any fossils of prey animals for the ichthyosaurs to feed on, just that of invertebrates like clams and ammonites.

“Once it became clear that there was nothing for them to eat here, and there were large adult Shonisaurus along with embryos and newborns but no juveniles, we started to seriously consider whether this might have been a birthing ground,” said lead author Neil Kelley, an Assistant Professor at Vanderbilt University.

"Combined with some of the skeletons that were collected back in the 1950s and 1960s that are at the Nevada State Museum in Las Vegas, it’s likely we’ll eventually have enough fossil material to finally accurately reconstruct what a Shonisaurus skeleton looked like.”

The 3D scans of the site are now available for other researchers and the public to study and view via the open-source Smithsonian’s Voyager platform: https://3d.si.edu/enter-sea-dragon.