Dhofar, Oman’s southernmost region, offers a unique blend of tropical and temperate diving, with carpets of kelp and seaweeds, diverse marine life, a range of endemic tropical species, sea turtles, whale sharks, manta rays and Arabian Sea humpback whales. Paul Flandinette has the story.

Contributed by

Factfile

DIVE OPERATORS

There are now many diving and snorkelling operators in Oman. The ones I know well and dive with are:

MUSANDAM

Ras Musandam Divers

rasmusandamdiver.com

CAPITAL AREA

Euro Divers

euro-divers.com

Extra Divers

extradivers-worldwide.com

Omanta Scuba Diving Academy

divescover.com

SeaOman

seaoman.com

DHOFAR

ABT Divers

abtdivers.com

Extra Divers Oman Explorer

extradivers-worldwide.com

It is late May in the Arabian Sea, and the rumblings of one of the world’s most powerful weather systems are growing stronger, producing a massive transformation of an underwater world that occurs nowhere else.

Dhofar, the southernmost region of Oman, is a unique place. Each summer, between the months of June and September, the region experiences the effects of the southwest monsoon, or Khareef as it is known locally (Arabic for “autumn”). The south-westerly monsoon winds grow stronger and heavy seas lash the Dhofari coastline. These winds weave their magic on land by bringing weeks of coastal rain and condensing fog that turn the landscape from an arid wilderness into a wonderland of lush green hills, flower-filled meadows and waterfalls. More rain falls on Dhofar during this time than the whole of Arabia combined in a year, and the landscape quickly resembles the green hills of Ireland. When the rains end, the greenery progressively dies, and the arid conditions return.

While the effects of the Khareef on land are plain for all to see, the enormous changes it brings to Dhofar’s underwater world are seen by just a few. Diving is not allowed during the Khareef months, but when it resumes in early October, we enter a world of turbid, green waters.

Carpets of seaweed

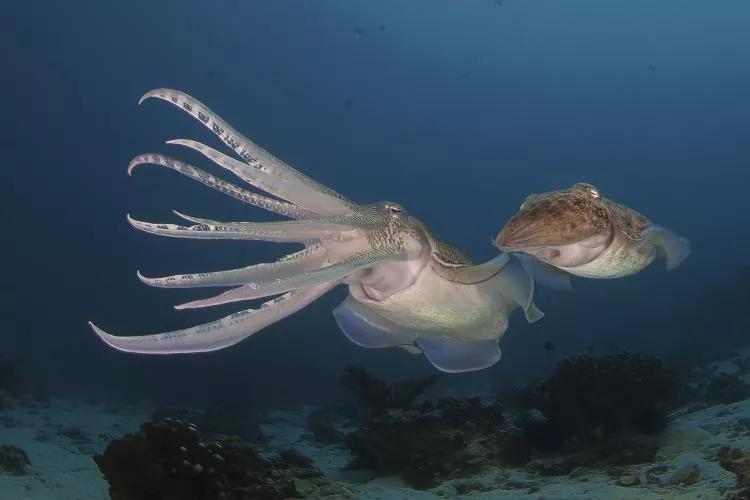

We also see something else that is truly remarkable in a tropical sea—carpets of seaweed. In the rocky shallows, sargassum seaweeds, kelp, red and green algae have grown rapidly during the summer and now dominate the seascape. It can be a strange experience for someone used to diving in temperate and tropical waters. Here, you will get both on the same dive.

With this abundance of seaweed, diving in Dhofar would be similar to diving in the coastal areas of Norway or Scotland, were it not for the presence of tropical species. When gliding over carpets of kelp or finning around taller growths of seaweed, one can encounter tropical, Indo-Pacific species such as the Oman anemonefish, stingrays, colourful parrotfish, moray eels or even a cockatoo waspfish (Ablabys taenianotus) resting under the seaweed.

Meanwhile, underneath the dense growth, coral communities wait for the seaweeds to disappear and once again have access to sunlight to grow and prosper during the winter months. This unique coexistence of temperate seaweeds and tropical coral communities occurs nowhere else on the planet. So, how and why does this happen?

The monsoons

The marine climate of the Arabian Sea is dominated by the seasonally alternating monsoons. In the winter, from December to March, the northeast monsoon carries cool, dry air from the Indian subcontinent to the Arabian Sea. However, it is the summer southwest monsoon that has the greatest impact on the region that stretches from Somalia to Oman along the western margin of the Arabian Sea.

Strong south-westerly winds (known as the Findlater Jet) blow parallel to the shores of Somalia, Yemen and Oman, creating a coastal upwelling from deep waters. The south-westerly winds generate a powerful current that pushes the coastal waters northeast along Dhofar’s coast, equal to the volume of the water carried by the Gulf Stream.

The Earth’s rotation deflects this large volume of water eastwards, leaving a vacuum near the coast. Cold, deep water rushes up to fill the gap creating a “wind-driven upwelling.” Surface water temperatures near the coast drop from 28°C in May to 17-19°C in August. Although wind-driven upwellings happen in other places, such as along the coast of Chile, Mauritania and Namibia under the influence of the trade winds, the seasonality of the Omani upwelling is unique.

The water coming up from depths of around 150 to 200 metres is relatively poor in oxygen but is extremely nutrient-rich, generated by hundreds of years of decomposition of falling organic matter by deep-sea microorganisms. This enormous input of nutrients into the surface water, bathed in hours of bright sunlight, triggers the development of a massive three-month-long bloom of phytoplankton that is carried hundreds of kilometres offshore. Meanwhile, in shallow waters, this bloom also feeds a variety of fast-growing seaweeds.

Marine life

In these southern waters, the temperature, currents and seasonal abundance of food support a wide range of endemic tropical species, including the Oman anemonefish (Amphiprion omanensis), an abalone (Haliotis mariae), the Dhofar parrotfish (Scarus zufar) and, perhaps the most majestic of all, the magnificent, but elusive, Arabian Sea humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). Just 70 to 80 individuals form an endangered sub-group of the species, which, thanks to the effects of the Khareef, uniquely remain in the Arabian Sea to both breed and feed, unlike other humpback whales that must migrate to either feed in polar waters or breed and give birth in shallow tropical bays.

By the end of September, the south-westerly winds subside, the upwelling ceases and the supply of deep-water nutrients ends. Water temperatures slowly return to tropical levels and the seaweeds and algae, now deprived of mineral nutrients, progressively die off or are consumed by grazers, disappearing completely by May when the cycle begins once again.

Diving

For those who prefer to dive in clearer waters, Oman’s productive seas offer world-class diving and many opportunities for exciting encounters. Oman is one of the least-known diving destinations in the entire Indo-Pacific, even though it is easier to reach for European divers than most other warm-water destinations.

With a coastline of over 3,000km, Oman’s seas stretch across three oceanic basins, each with very different characteristics. The Gulf of Oman is one of the world’s busiest sea lanes—some 40 percent of all the world’s oil is transported through these waters. With an average depth of just 35 metres, it is subject to high levels of evaporation, making the water very salty.

Musadam

Musandam, in the north, with its many fjords and rocky inlets, is known as the Norway of Arabia. Its dramatic landscapes and azure waters are very inviting. Healthy corals, whale sharks (in season), turtles and a myriad of colourful reef fish can be seen.

Daymaniyat Islands

Close to the capital, Muscat, lie the Daymaniyat Islands, a UNESCO protected nature reserve. The island group comprises nine islands that offer some of the very best diving not just in Oman, but the whole region. There are dozens of dive sites where you will find a rich diversity of marine life at a range of depths that are suitable for novices and advanced divers alike.

Here, you will find healthy colonies of both hard and soft corals, although as elsewhere, corals are susceptible to climate change, pollution, cyclones and human impact, all of which can adversely affect their long-term survival. However, coral bleaching, which is increasingly common and deadly in many parts of the world, often appears to be reversible in Oman and so far, has rarely led to massive loss. Again, this is due to the unique oceanography of Oman’s seas.

In the Arabian Sea, the summer upwelling of colder water protects the reefs from overheating. In the Sea of Oman, minor upwelling events force thermoclines upwards, where they meet the surface waters that have been heated by the sun. The two layers of water do not mix, allowing the layer of cool water to act as a protective blanket for the corals below.

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are regular visitors between June and October, sometimes seen in large aggregations of 20 or more. Sea turtles and several species of moray eels abound, while colourful reef fish and dense carpets of corals are part of the rich tapestry of life on the reefs.

Ras Al Jinz Turtle Reserve

At Ras Al Hadd, where the Sea of Oman meets the Arabian Sea, is the Ras Al Jinz Turtle Reserve. This is Oman’s only official centre that provides expert guided experiences for visitors to watch green turtles nesting and laying eggs, and hatchlings taking their first ungainly steps to the sea.

Green turtles (Chelonia mydas) nest all year round at Ras al Jinz, with the peak nesting season between June and September and the lesser nesting season from October to May. This nesting pattern is linked to the seasonality of the southwest monsoon and is extremely rare, if not unique, amongst other turtle populations elsewhere.

Each year, an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 female turtles return to Ras Al Jinz to dig nests and lay eggs on the same beaches where they hatched some 25 to 35 years earlier. This high number of turtles returning to nest makes Ras Al Jinz one of the world’s most important turtle rookeries.

Capital area

Dive sites at Bandar Khayran, Fahal Island and Ras abu Doud in the capital area frequently throw up some surprises, such as encounters with ocean sunfish (Mola mola) or false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens).

Hallaniyat Islands

One of the most exciting places to dive is the pristine Hallaniyat Islands, which lie about 40km east of the Dhofar mainland. This group of five islands forms a remote archipelago that sees relatively low numbers of divers, and the dive sites are best reached from a liveaboard vessel. Here, there are opportunities to see large schools of fish, manta rays, mobulas and the Arabian Sea humpback whale.

Salalah and Mirbat

Other dive sites in Salalah and especially Mirbat could get you an encounter with the occasional shark, the stunningly beautiful dragon moray eel (Enchelycore pardalis) or the endemic and rather strange-looking two-faced toadfish (Bifax licinia).

Final thoughts

The productivity of Oman’s seas is massively influenced by the unique effects of the Khareef. With some 1,600 species of fish, nearly 200 species of hard and soft corals and 20 species of cetaceans that either reside here or migrate through, Oman’s seas are amongst some of the world’s most bio-diverse waters. In an underwater world that remains largely unexplored, Oman’s seas still hold many secrets waiting to be revealed. ■