Why whales don't seem to get cancer

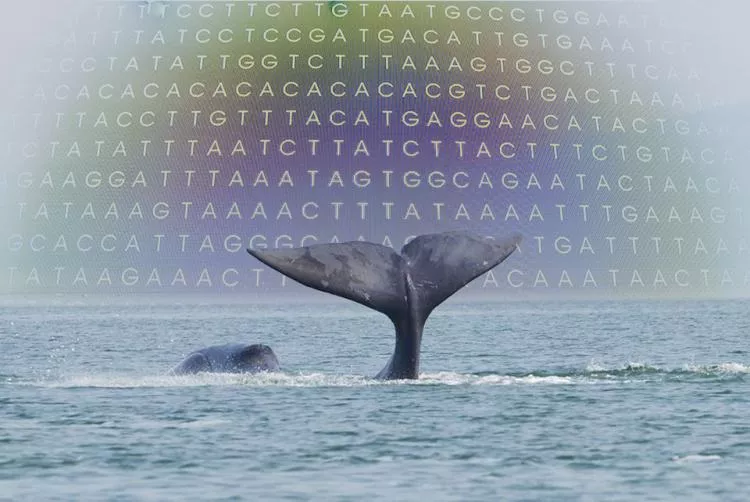

Cetaceans are the longest-living species of mammals and the largest in the history of the planet. They have developed mechanisms against diseases such as cancer, although the underlying molecular bases of these remain unknown.

Cetaceans were not limited by gravity in the buoyant marine environment and evolved multiple giant forms, exemplified today by the largest animal that has ever lived: the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus).

There are tradeoffs, however, associated with large body size, including a higher lifetime risk of cancer due to a greater number of somatic cell divisions over time. The largest whales can have ∼1,000 times more cells than a human, with long lifespans, leaving them theoretically susceptible to cancer.

However, large-bodied and long-lived animals do not suffer higher risks of cancer mortality than humans—an observation known as Peto’s Paradox.

Gene repair

Comparative genomic results suggest that the evolution of cetacean gigantism was accompanied by strong selection on pathways that are directly linked to cancer.

A team of researchers led by Marc Tollis of the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University in the US constructed – for the first time – the complete genome of a humpback whale, and then compared it to existing genomes for 10 other species.

The results confirmed earlier research that found that gigantism is linked to the duplication of many genes that are associated with cell function, DNA repair and ageing.

Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus), for instance, have been estimated to live for at least 200 years, and their genome shows positive selection for genes that are important components of the DNA repair pathway. The species also has duplications in other genes that influence gene repair and cellular growth.