Comprising two tropical island groups located 932km southeast of Miami, the Turks and Caicos Islands are a British Overseas Territory in the Lucayan (or Bahama) Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. Underwater photographer Scott Johnson describes the easy diving found here as he meets the challenge of capturing images of mouth-brooding behavior in fishes.

Contributed by

“Is this an exercise in futility, stupidity, or both?” I asked myself as I ascended from the second shallow dive of the day to take a short break, grab a fresh tank, and then give it another go. The Turks & Caicos Aggressor II, which my wife Lauren and I think of as our “home away from home” (since we are aboard the yacht at least once per year), was currently moored above the Driveway dive site in West Caicos. It was an appropriate name for the site as I felt like Lady Luck had run over me and then backed up a few times for good measure thus far today, frustrating my photographic efforts.

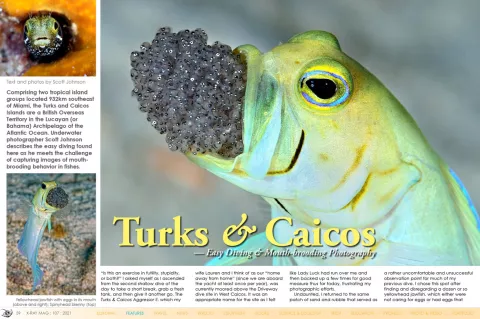

Undaunted, I returned to the same patch of sand and rubble that served as a rather uncomfortable and unsuccessful observation point for much of my previous dive. I chose this spot after finding and disregarding a dozen or so yellowhead jawfish, which either were not caring for eggs or had eggs that were too immature. Fortunately, the male yellowhead jawfish only a meter in front of me had a mouth full of silver eggs, which would likely hatch within the next 24 hours. Now, it was back to the hard part—waiting.

When male and female yellowheads mate, the female releases an egg packet, which the male fertilizes, scoops up in his mouth and then orally incubates for seven to nine days until the fry hatch. In order to capture “the shot,” which is of the male jawfish aerating the eggs by spitting them out and then almost instantaneously sucking them back inside, I lay as motionless as possible and breathed at a steady, rhythmic pace to allow the protective parent to realize I was no threat. Finally, after thirty minutes of missing the in-the-blink-on-an-eye aerations, I squeezed the shutter at just the right moment and framed the silver eggs before the jawfish returned them to his mouth. With an appreciative nod to the diligent father, I slowly backed away and finished another beautiful dive in the azure waters of Turks and Caicos.

Countless coral skeletons

The Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI) are a British Overseas Territory located 932km southeast of Miami in the US state of Florida, 63km southeast of Mayaguana in the Bahamas, and 161km due north of Hispaniola (Haiti/Dominican Republic). Over 40 enchanting islands and cays, which account for 389 sq km of beckoning beaches, are separated into two distinct groups by the 35km-wide and 2,195m-deep Turks Island (or Columbus) Passage. The Caicos Islands, by far the larger of the two chains, run east to west and include West Caicos, Providenciales (Provo), North Caicos, Middle or Grand Caicos, East Caicos and South Caicos, as well as small cays like French Cay, Parrot Cay and Pine Cay. The Turks Islands stretch north to south and contain only two sizeable landmasses in Grand Turk and Salt Cay.

The Bahamas and TCI are divided by the Caicos Passage and combine to form the Lucayan Archipelago. This dotted string of islands represents the pinnacles of coral banks that were formed in a similar manner to the Florida Keys. These ancient reefs were repeatedly covered, uncovered, and sculpted by fluctuating sea levels, which were triggered by changes in the earth’s temperature, and consequently, the size of the polar ice caps. The islands and cays we see today are the covered crests of untold numbers of coral skeletons, which collectively form the terrestrialized reefs.

Bold, beautiful and fun

“Not going to happen,” said Rob Smith, the Turks & Caicos Aggressor II’s stout engineer and trusty dive guide, when he saw me trying to carry one of our bags from the dive deck to our cabin. This had become somewhat of a game between us through the years as the whole crew took pride in making sure guests never do anything remotely resembling work. I considered it a major victory if I could zip my own wetsuit before a crew member beat me to it.

The “no work, live easy” theme aboard the yacht was generally continued underwater, as the diving in TCI was ridiculously uncomplicated, exciting and dependable. Basically, guests merely needed to jump off the back of the 36.6m luxury yacht once the vessel was moored. Mild to no currents, warm water, and 30m of visibility were the normal diving conditions.

The islands here are predominantly encircled by shallow-water, “spur-and-groove” reefs. Follow a groove away from an island and it will generally lead you to a dramatic drop-off and the tranquil, cobalt blue of open water. Panoramic views of the walls can be breathtaking due to the water clarity and the evident health of the reefs. Variety is measured more by what you see during your explorations than the variances in the life or typography from one site to the next. Big marine animal sightings are common throughout the archipelago. Believe it or not, guests get so used to seeing rays, sharks and turtles during a charter that they often go in search of a nice channel-clinging crab or spiny lobster to entertain them. We divers can be a fickle lot.

Underwater games

Provo’s Thunderdome or The Dome was a “wreckish” dive unlike any other in the world and one of the best night dives in the Caribbean to boot. The Dome represented the remains of a French television game show entitled “Escape from Pago Pago Island,” which was filmed in 1992 and 1993. The steel structure that was once the centerpiece of the set now lay twisted and partially disassembled by storm-induced waves. You had to dig in the sand to make it past 10m, so there was plenty of bottom time for examining the area. Roughhead blennies, Pederson’s shrimp and skeleton shrimp were readily found on remnants of the abandoned set. Spotted drums, schoolmasters and large green morays frequented the interior of the most intact section.

Brazen black jacks could be a pain at night because they often tried to use divers’ lights as hunting aids. For example, one rushed out of the darkness to grab a tiny Caribbean reef squid before I even had the chance to photograph it, making me feel like an accomplice. Overall, night dives at The Dome reminded me of treasure hunts for living booty in the form of banded clinging crabs, flamingo tongues and other exquisite residents.

West Caicos and French Cay were uninhabited islands. About all one would find on land were birds, insects, lizards and scrub plants. Life beneath the surface was a totally different story. The neon-colored fish, bushy gorgonians and robust sponges were welcome contrasts to the terrestrial starkness.

Underwater fly-bys were a common occurrence at West Caicos. I made it a habit of scanning the blue water in case a manta ray, spotted eagle ray or sea turtle was cruising along the wall. The Anchor was West Caicos’ signature dive. A huge, 17th-century anchor was embedded in the wall of a narrow channel at 21m. Despite its size and shape, the sponge-encrusted anchor was easy to miss if you were not paying close attention to the reef. A dive guide came in handy on this one.

Where the wild things roam

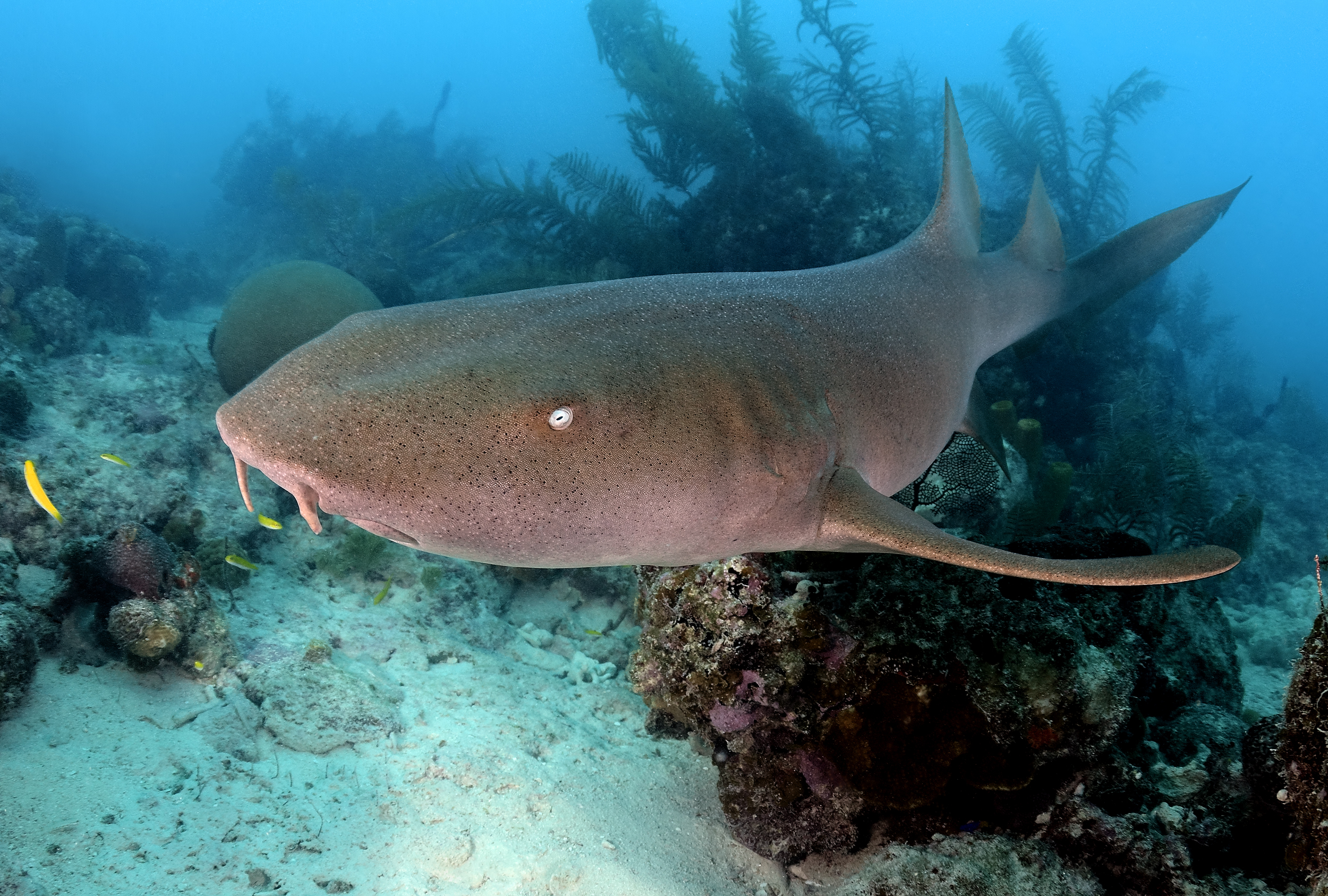

French Cay is where the wild things swim and where liveaboards rule. Strong trade winds and waves often make the 29km crossing south from Provo an uncomfortable challenge for day boats. The sites Double D, G Spot, Half Mile, Rock & Roll and West Sand Split are all similar in that they were obviously named by drunken, modern-day pirates and because each usually offers plenty of sharks, schooling horse-eye jacks and industrious jawfish. Nurse sharks use French Cay as a romantic getaway each July and August when they congregate in the shallows to mate.

Caribbean reef sharks often appear just below the surface near the dive deck at these sites as if responding to the hum of the generators. Guests often pause before making a giant stride entry as they wonder what might happen if he or she lands on a muscular, scaly back. You know each is thinking, “OMG! OMG! OMG!” During the dives, the sentinel sharks are ever-present. They circle the yacht. They circle the divers. And they circle one another.

During a dive at Rock & Roll, I positioned my back to the sun, framed one of the approaching sharks in my Aquatica viewfinder and then fired a quick burst of shots. The weak electrical impulses generated by my strobes prompted the curious shark to bump into me. But I did not mind because the underwater world of the TCI was exactly where I wanted to be.

The destination of “easy”

The TCI’s “Beautiful by Nature” slogan was spot on. The picturesque, flat islands offered miles of lonely white sandy beaches, bathed in balmy breezes and lapped by turquoise waters. Our days and nights were spent leisurely diving, eating and relaxing—quite decadently, I must confess. Ultimately, TCI was the destination of “easy.” Life aboard the Turks & Caicos Aggressor II was easy. The diving was easy. And, of course, swimming with the sharks was easy. The only things that were not easy were photographing the mouth-brooding jawfish and having to go back home at the end of the charter trip. ■