In the first of a new two-part series, Simon Pridmore describes a few equipment-related problems that divers commonly encounter and offers some tips on how to avoid or deal with them.

Contributed by

For the many dives we do which are uneventful, there is always the odd dive where something takes place that reminds us of our vulnerability. This often involves the failure of a piece of equipment and many of us are guilty of not thinking too deeply about what to do if something goes wrong or how to prevent it from happening in the first place.

In this, the first of two articles on the subject, I run through a few problems that you will probably find yourself having to deal with at some point in your diving career, and run through some precautions to take and drills to practise, so you can be as well prepared as possible. Technical divers refer to this process as planning for the “what-ifs.”

O-ring blowout

The O-ring on the cylinder valve (if you are using a regulator with a yoke/A-clamp fitting) is a tiny but crucial link in the process of moving the air from the cylinder to your lungs. If this O-ring is missing or damaged, a seal cannot form, and air will escape when you attach your regulator and then open the cylinder valve.

The loud hiss of high-pressure air escaping tells you that either you put the regulator on incorrectly or you have an O-ring problem. Whichever it is, you will almost certainly immediately become the centre of unwanted attention. You can avoid this by making a point of checking that the O-ring is in place, untorn and unfrayed, before you fit the regulator, and by positioning your regulator first stage orifice snugly over it before tightening the yoke.

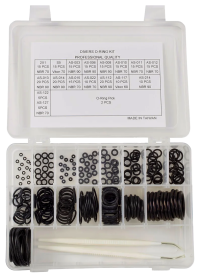

O-rings are designed to last many years, but in the world of scuba diving, factors such as salt, heat and humidity can reduce their lifespan considerably. If the O-ring is absent or looks shabby, replace it. Most dive shops and online stores sell a handy little bullet-shaped tin, which contains spare O-rings and a pick to help you remove the old O-ring from the tank valve. Before these kits became common, good instructors used to keep a couple of spare new O-rings on their dive watch or computer strap, knowing that a leaky O-ring often messes up carefully scheduled plans.

It is good to be self-sufficient and have your own replacement O-rings readily on hand, so you do not have to ask for help at a time when everyone around you is getting their own gear together and has their own problems to solve. You will also be perfectly placed to help dive buddies if their cylinders start hissing at them when they set up their gear.

Underwater, it is very unusual for the cylinder valve O-ring to fail, but it has happened to me. Then, the only way to fix the problem is to shut down the valve, which is possible if you are diving doubles or carrying another cylinder containing a breathable gas for the depth you are at. If you have just one cylinder, your only option is to go to the surface, ideally with a solicitous buddy nearby ready to hand over his or her octopus if you run out of air on the way up. There is no reason to panic, just do not delay. You do not have much hesitation time. Tests suggest that your cylinder will be completely empty in only a few minutes.

How do you know it has happened? The sound is unmistakable. It is a deafening explosion behind your head that does not stop. Glance at your pressure gauge and you will see the needle moving. Even if the explosion did not make your mind up, this is a clear sign that you need to stop wondering and head up. You will still be able to breathe through the regulator as you ascend—while the air lasts. Do not bother with your safety stop if you are on a no-deco dive. It is infinitely better to miss it than run out of air underwater.

Reduce risk by doing these things:

• Check your cylinder valve O-ring before every dive;

• Replace broken O-rings when you detect even a slight leak;

• Avoid going into deco when you are diving with only one cylinder; and

• Practise air-sharing ascents with your buddies from time to time.

Regulator free-flow

Having discussed one way by which you can quickly lose the air in your cylinder during a dive, I should also mention another way. Your regulator is designed with a downstream valve so that, if it fails, air will pour out of your scuba cylinder uncontrollably until it is empty. When you first learnt to dive, your instructor told you this was a good thing, and you went along with that because, at the time, you were more worried about suddenly having no air to breathe rather than having too much.

Of course, it is not a good thing.

In your beginner course, you probably simulated the experience of breathing across the powerful stream of air coming from a free-flowing regulator, while sitting on the seabed or the bottom of a pool. This is good training in one respect, in that, having done this in a controlled environment, you will know what to do if it happens for real.

On the other hand, the training is flawed in that this exercise might mislead you into thinking that the thing to do if you have a free-flowing regulator is to stay where you are. In fact, as with a blown valve O-ring, unless you have an independent air source to switch to, rather than stay where you are and breathe in more carefully, the thing to do is to move towards the surface with minimum delay, again ideally with your buddy right beside you.

Proactive measures you can take to make sure your regulator does not free-flow include:

• Keeping your octopus well secured to your BCD so it never drags in the sand or against the reef and gets damaged;

• Keeping your octopus’ venturi-effect lever (if there is one) at negative when it is not in use;

• Rinsing out both regulator second stages well, post-dive; and

• Keeping your regulator well maintained. Have it serviced at the first sign of a problem.

Mouthpiece malfunction

Staying with regulator problems, second-stage mouthpieces can be the cause of unusual issues. The rubber can split, and you can find yourself inhaling a fine mist of seawater with each breath, or the cable tie securing the mouthpiece can snap, leaving the mouthpiece attached to the regulator by friction only. At some point, that will not be enough, and the two parts will separate, leaving you with a mouthpiece between your teeth, a mouthful of water and nothing to breathe.

Even a small defect can turn out to be more than just an inconvenience. A diver once approached me and said that he loved the sport but was going to quit because after every dive he would get chest pains and flu symptoms for about 24 hours. I checked his regulator mouthpiece. Sure enough, there was a tiny split, so we changed it and the problem disappeared. During each dive, the diver had been inhaling seawater with every breath and giving himself a bizarre form of self-induced bronchopneumonia.

Precautions:

• Make a point of checking both the mouthpiece and the cable tie that holds it in place, as part of your pre-dive equipment check; and

• Carry spares of each in your Save-a-Dive kit.

Runaway cylinder

This is something that happens much more frequently than it should. You are swimming along, when suddenly you feel unbalanced, and the regulator in your mouth starts to tug your head backwards. Your buddy points at you in horror, then disappears from view. The next thing you feel is someone shoving you from behind. At this point, you realise that your cylinder must have slipped out of the BCD cam strap, and your buddy is trying to push it back in.

If you have no buddy around, you can fix this yourself. If you are close to the seabed, first make sure the seabed is not covered with fragile marine life. Find an empty patch of sand or rock. Then, settle down on your knees, reach behind you with your right hand to support the cylinder, undo the BCD and shrug it off as if you were removing a jacket, left arm first, keeping your teeth tightly clamped onto the regulator mouthpiece.

Bring the whole setup around to the front of your body, keeping it very close to you (especially if your weights are in the BCD), and refit the cam strap calmly (and tightly this time) before donning the BCD again and resuming your dive.

Even if the seabed is not close, you may be surprised at how, with a little practice, you can master this drill while staying neutrally buoyant in midwater. Try doing it in a pool or shallow confined water first. The drill will improve your buoyancy control as well as boost your underwater confidence. Do not practise it alone though. Get a buddy to watch over you. Then, do the same for them while they try it.

Of course, it is much better if your cylinder never falls out at all. One way to reduce the likelihood of this happening is to soak the cam-strap with water before you lock it down onto the cylinder. But, the best way, and the method most guaranteed to have a 100 percent success rate, is to buy a BCD with twin cam-straps. Then the whole last section of this article becomes irrelevant.

In my column in the next issue, I will go through a few more equipment trials and tribulations. ■