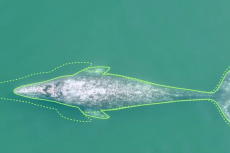

Orca grandmothers improve survival of their grandoffspring

Orca grandmothers increase the survival of their grandoffspring, and these effects are greatest when grandmothers are no longer reproducing.

In a study involving 378 orcas (or killer whales), researchers observed the first non-human example of the "grandmother effect" in a menopausal species.

This is when post-reproductive grandmothers (in this case, orcas) assist other members of the species with their offspring, thereby improving the young ones’ chances of survival. It was found that these post-reproductive orcas had the largest beneficial impact on their grandoffspring’s survival chances.

The findings of the study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal, was based on more than 40 years of census data gathered by the Center for Whale Research and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

The research team included scientists from the University of Exeter, US Centre for Whale Research and Canada’s Pacific Biological Station. They focused on two resident orca groups off the coasts of Washington in the US and British Columbia in Canada.

For calves whose maternal grandmother died within the last two years, they had a mortality rate that was 4.5 times higher than those with a living grandmother, in the two years following the death.

Interestingly, this effect was especially true whenever the population of Chinook salmon (their food source) was low. In years when the fish population flourished, this effect diminished.

Previous research showed that the reason for this was the post-reproductive grandmothers’ knowledge and experience when foraging for food.

“We have previously shown that post-reproductive grandmothers lead the group around foraging grounds, and that they are important in doing that in times of need, when the salmon are scarce,” explained senior author Dan Franks from the the University of York.

Importance of grandmothers

With the progressive decrease of salmon populations, the grandmothers’ role in this capacity will become even more important in orca populations.

In addition, the grandmothers have been known to directly share food with their younger relatives, prompting the researchers to suspect that some babysitting was involved as well.

Such “abilities” may explain why the phenomenon of menopause may have evolved in some species and not others.

“Our new findings show that just as in humans, grandmothers that have gone through menopause are better able to help their grandoffspring and these benefits to the family group can help explain why menopause has evolved in killer whales just as it has in humans,” said co-author Prof Darren Croft from the University of Exeter.

Besides orcas, menopause has so far been found to have evolved in humans, short-finned pilot whales, narwhals and beluga.

“The study suggests that breeding grandmothers are not able to provide the same level of support as grandmothers who no longer breed. This means that the evolution of menopause has increased a grandmother’s capacity to help her grandoffspring,” said Dr Franks.