The Oldenburg, which was originally named Pungo, was built in 1914 to carry bananas between Cameron and Germany. It was drawn into World War I in 1915, put into German service and rebuilt as a raider ship. René B. Andersen shares the story of the ship and takes us on a dive to the wreck.

Contributed by

WWI raider ships were merchant vessels and preferably refrigerator ships because they were faster than regular ships. They were equipped with hidden cannons and mines and sailed under false names and flags, with camouflaged armaments and crew. Cloaked in this manner, the raiders were able to get past the English blockade, after which they were free to lay mines or approach enemy cargo ships in order to raid or sink them.

When Pungo was rebuilt as a raider ship, it was fitted with four 15cm cannons and a 10.5cm cannon, along with two torpedo tubes and 500 mines. The raider then undertook several raids in the Atlantic Ocean and the Kattegat, Skagerrak and Baltic seas from 1915 to 1919, during which the vessel switched names several times, from Pungo to Möve to Vineta.

During this period, the ship captured and sank 42 ships. Among its many victims was the British battleship HMS King Edward, which was sunk by one of its mines. Two other casualties were the English ship Georgic, which was sunk with 1,200 horses on board, and the cargo ship Otaki, which was armed and resisted but could not match its opponent, Möve. This made Möve the most successful raider ship. But the war ended for Germany in 1918, and after the Treaty of Versailles, the ship was handed over to English ownership as a war reparation. Now renamed Greenbrier, it once again freighted bananas. Then, in 1933, a German shipping company bought the ship and named it Oldenburg.

WWII cargo ship

During WWII, Oldenburg was enlisted into marine service once again but with a quieter assignment as a cargo ship sailing between Germany and Norway for the German occupiers. But before entering service, the vessel was outfitted with anti-aircraft and ship guns. It looked like the ship would make it through the war, until one fateful day on 7 April 1945, when it was at anchor on the western side of Vadheim in Norway’s Sognefjorden, with a cargo of fish destined for Germany. Oldenburg was part of a convoy with another merchant vessel and two outpost ships, V-5301 and V-5302, which were old whaling boats that were armed.

In the morning, they came under attack from 21 English Beaufighters (which were heavily armed with machine cannons and rockets) and their escort of 16 Mustang fighter aircraft. If the crews of the convoy vessels thought that the high mountains around the fjord would offer them some protection, they were mistaken. The ship’s anti-aircraft guns started firing but in vain, and several rockets hit Oldenburg under the waterline, after which the ship took on water and began to sink.

There is an old picture in which Oldenburg is shown lopsided and burning. Seven anti-aircraft personnel and only one of the ship’s crew were wounded in the attack. Albert Carr, a former pilot in the 489th squadron, who took part in the attack, visited Vadheim in 1987. He recalled that he expected a warm welcome and that was exactly what he got. German ships were generally well-armed, and although his own aircraft was hit, he still managed to fly it back to base.

Afterwards, the English aircraft came into battle with German aircraft in the outer part of Sognefjorden. The German aircraft came from a base near the city of Bergen. Both sides suffered losses. The other cargo ship, MS Wolfgang L.M. Russ, survived the attack, with one fatality and three wounded. It was later sunk on the 4th of May in Danish waters around Århus, while it was on the way to Germany with ammunition.

Vadheim

To get closer to the wreck (which lies on the western side of the fjord, if you are driving on E39), one can take the small road (50m before or after the river on the western side of the city) that goes down to a red house and a larger parking area. It is on private property, but the owner does not mind at all if you park there, as long as you put money in the mailbox, which is placed near the staircase. It is a fair arrangement, and in return, he has put up a staircase, so it is easy to get into the water. I have spoken with the owner a few times about his plans, which is to build a rental house that would be perfect for divers.

From the parking area, you can see the 80m out to where the wreck is located, and there is normally a buoy on it. Otherwise, check norgeibilder.no. Zoom in and you can see the buoy.

Diving

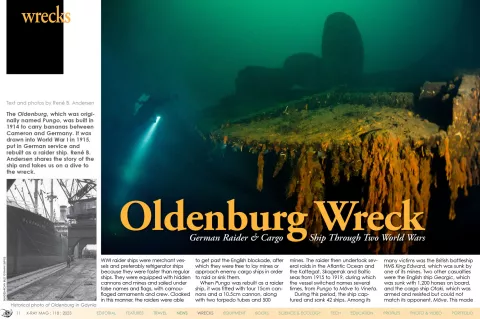

Descending to the wreck, the first thing you will notice is the stern, at a depth of 27m, and it is clear to see how the ship is resting on its starboard side. The stern, with its big hawsepipes, rises some metres above the sea bottom, and it appears the wreck has slid down the slope. The anchor and chain are gone, but the anchor winch is still on the deck.

A little farther down lies a platform for anti-aircraft cannons, and possibly a 20mm flak gun. There is steel plating around the edge, but it lies upside-down in the mud, and it appears as though the gun is still there. After the first cargo hold, one comes to the mast and crane arms, which have fallen down to the sea floor with some cables still connected to the railing. It looks interesting the way the cables appear as if they are overgrown. The crow’s nest still hangs on the mast. It was probably where crew members stood on the lookout, scouting for ships during raids.

The bell was salvaged in the late ‘80s, although it was hard to find because it was located above the crow’s nest where no one had thought to look for it.

The superstructure is at a depth of around 45m and is still in good condition, with its two levels with railings around the rim. There is even glass in some of the windows, but the bridge is missing, or rather, it is lying in a pile on the sea bottom, because it was just made of wood. You can still see the bolt holes, after the steering wheel console, which was salvaged in the early ‘90s. This could not have been an easy task, considering its 240kg weight. By coincidence, I got in contact with wreck expert Morten Stridh, who was nice enough to send me a photo of the steering wheel console in perfect condition, as well as a photo of the ship’s bell, with the ship’s old name Möve on it.

Part of the wooden deck has rotted and has large holes through which one can swim. But with the wreck’s age and the silty bottom, one must be very careful. In 1990, a diver lost his life doing this. Behind the bridge, I saw a milky-white fog that continued downward, limiting the visibility. Maybe it had something to do with the fresh water from rivers in the surrounding area.

There were several davits for the lifeboats, which were nicely overgrown with peacock worms and sealoch anemone. There was also some sort of structure, but when I looked at the old photos of the ship, I saw that this was where the ship’s funnel once stood. I must admit I did not look for it on the seabed.

Sunlight streamed down into the engine room. There was still glass in some of the portholes and some of the covers were open. Here, it is possible to look down and see inside the ship, but I did not get to do so, because I was occupied with photographing the wreck.

Farther down, there was one more structure, and in front of it stood what looked like a pressure tank. From this section of the wreck and towards the bridge, I saw several gun turrets. The ship had been heavily armed with anti-aircraft guns. Unfortunately, there were no cannons in the turrets. I will definitely take a closer look next time.

The second mast also had a nicely decorated deck with lots of tubeworms, but now the depth was around 60m. Down towards the stern, there was a walkway that led out to both sides of the railing. Behind the stern, there were some more superstructures that I would look at the next time.

The bottom was covered with a lot of debris, which probably came from the superstructure and cabins as they rusted away. Going around to the bottom of the ship, one could see the propeller and rudder a little farther up. They were both in perfect condition, and it was a beautiful sight. With the way the wreck lay, the propeller stood completely free of the seafloor, in open water. One could swim under it. But one thing caught my eye—the large rocks located on the rudder. How did they end up there?

The depth here was 75m, so dive time was passing by quickly. After seven minutes, my computer told me it would take 30 minutes to surface with a deco stop. But there were still things that we needed to look at on the way up.

If you follow the wreck upwards and up to the bow, just keep going in that direction. There is a lead line, which goes up to 6 to 8 metres, which you can follow right up to the stairs where you can also place your stage bottles. There is no need to strain the body to lift them all up at once after deco. Instead of making a free ascent, you have the advantage of being able to swim along the edge. When you have 30 to 40 minutes of deco to pass, time goes a little faster when you have things that have been tossed to the sea bottom to look at. I also managed to find a few nudibranchs.

I previously dived the Oldenburg wreck back in 2010 on air, which limited the depth to 40m. This time, I was on a rebreather which enabled me to see the whole wreck down to 75m. But there were many details that I need to look closer at next time—for example, the engine room, the stern with its superstructures, the guns on the bottom, and the superstructure at the wheelhouse, to name a few. Perhaps, I could also penetrate some of the holes in the wreck. The interior would make for a beautiful photo motif.

We got three dives on the Oldenburg on this trip, but we would definitely plan for more dives on the next trip. There is also the wreck of the steamship Ingerseks in Sognefjord (of almost the same size as Oldenburg), which I have not explored yet. But that is a story for another time...

I think it is impressive to find such a great wreck as the Oldenburg at a depth that can be dived from the shore. When you read the stories about it, you too would want to dive it. ■

See wreck location on map here: dykkepedia.com/wiki/Oldenburg

Source:

Toft, M. (2003). Havet tok. Selja Forlag