I first discovered freshwater eels in an estuary pool by the sea in Tahiti. There were usually about eight of the thick-bodied creatures, each over two metres long with triangular fins at their gills and vertically flattened tails. They would emerge from the shadows to swim languidly into the sunlight, undulating against the boulders, and turning on their backs to wriggle against the stones, as if this pool, these rocks and this morning’s rising sun were all that they needed to be happy. But the ones I found on the mountainside were smaller, and very secretive.

Contributed by

For a while, I kept an observation site high on the shoulder of a mountain on Tahiti’s sister island, as part of my studies of the local birds. I was trying to learn about the species of seabirds that nested there, which were, at the time, unknown.

That wet season brought record rainfall. One night, a metre of rain fell, and it ran down the side of the mountain and through my shelter. An eel slithered out from beneath the floor, saw me and retreated back out of sight. But soon it reappeared and glided to the nearby stream, but instead of swimming away, it dove straight down into the earth. Later, another eel came wending its way over the flowing forest floor, and it, too, disappeared underground.

There was a place where water poured out to make a fountain in the air. Here, there were channels cut beneath the trees by water—a world invisible, of passages known only to eels.

Encounters with an eel

In the tropical heat and high humidity, it was a great pleasure to be able to sink, at times, into the cool waters of one of the pools. At dusk, an eel appeared in the pool, and I began to see him lying on the bottom late in the day or early in the morning. But by the time I could return with my camera, he would always be gone. He would hide at the sound of my footsteps even when I was quite far away.

So, I began sneaking around in an effort to take his picture, and often crept down to the pool to see what he was doing. Once, he was lying immobile on his back on the surface and I went to get my camera, but by the time I returned, only his nose and eyes were visible in the darkness of a hole between two of the great stones.

Later, he seemed to be hunting for insects. I delicately picked a leaf from the surface to clear the view for a photograph, and like lightning, he struck my hand.

One afternoon, I threw him a grain of corn, and he responded by lifting his nostrils above the surface, presumably looking for the source of the alien item. He was not stupid!

As time passed, he became used to me, stopped fleeing at the sound of my footsteps, and no longer hid when my camera flashed into his pool. He came out into the open earlier, and stayed later, so that I was able to watch him in the daylight. He was well camouflaged lying there. Animals did not notice him when they approached to drink, but he was quite aware of them, through the slightest vibration at the water’s edge.

Another pool, another eel

Because of the eel, I looked upstream for another pool to bathe in and found one so deep that I could sit in it up to my chin. How beautiful it was to recline in those silken waters, looking up through the endless patterns of tropical foliage to the sky, in a supernatural silence ruffled only at times by the sound of the wind. There was even a flat rock to lay my head upon for comfort. Dreamy as I felt in that luxurious pool, a long time passed before I saw the enormous eel that inhabited it. He habitually looked out of his hole beside the rock upon which I rested my head, but I did not mind—it was such a pleasure lying there, dreaming, close beside the mysterious eel in my bath.

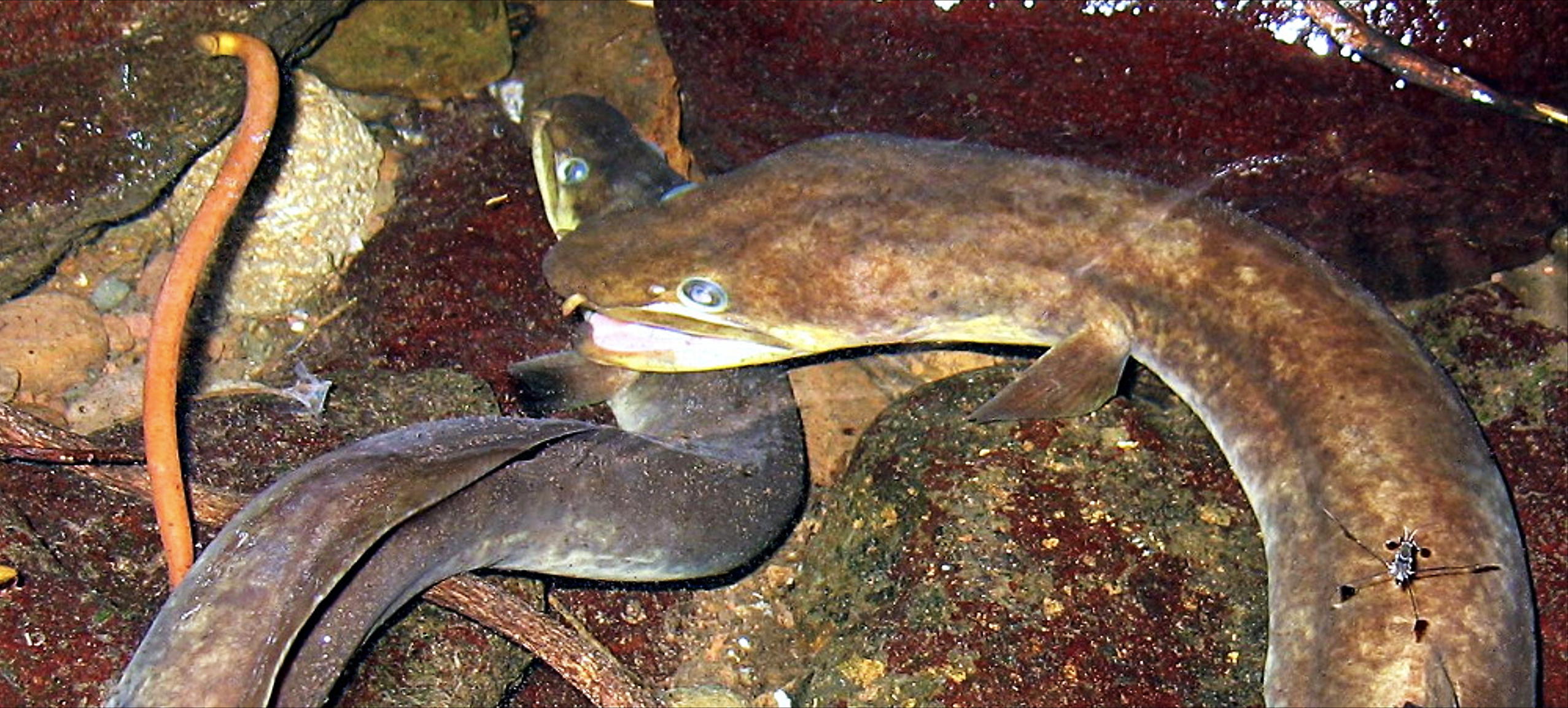

One night, it rained heavily and in the morning the stream was a churning dark river. One very large eel made his way upstream like a big snake and at nearly every pool, an eel showed a few coils at the surface, slicked with silvery water, as it shimmied away.

Sometimes, I crept along the big stones above the stream as darkness fell. There was an eel in nearly every pool, secretively gazing out. Some were tiny, sliding slowly from one stone to another, all but invisible. Others were very large. Some were on the move, and only a series of serpentine coils appeared with a few gleams and the softest splash. The eels came out at night, and like sharks, were bolder then.

But the largest one was the eel in my bathing pool, and at night he emerged from his hole. Once, while I manoeuvred for a photograph, he extended his length across the pool to the boulder where I stood, rested his head, and gazed up at me.

Eels hunting and feeding

One evening, I sat meditating above the eel’s pool as night fell. It was too dark to write, and I had gone out to sit with the birds as they gathered to fly into the trees. A group of juvenile junglefowl chattered and preened nearby and moved to the stream to drink. I was taking the occasional photograph, but in the darkness, could not, myself, see the eel sliding towards them, yet it is visible in one of my photographs (above).

The glistening blackness of the water suddenly moved, and the birds exploded away from a splash. The eel had caught the black chick. I leapt down, lifted the creature from the water, and found myself in battle with a powerful and very slippery animal, as muscular as a snake. It dropped the bird, which began flying across the surface to the shore. I reached out for it, but with unexpected power and speed, the eel unerringly clamped its mouth shut on the bird’s throat, wrenched itself from my grasp, and slithered back into the pool. I could not get the bird back. It was being violently shaken in water that was instantaneously opaque.

The eel blasted back into its hole, the image of haste as it tried to angle its prize through the small opening, apparently aware that I could interfere with it again. Finally, it succeeded in forcing the bird through, and into its subterranean passage. But it left its tail carelessly draped upon the rocks outside for some time.

Soon, strange sounds began to emerge from underground, rather like the sounds a toilet plunger makes and variations thereon. The eel was churning around.

From the little I could see of it, it had multiplied—three eels were thrashing together, turning over and over. A tiny eel came out and slid into the pool, then another.

As night came, there were eels everywhere, apparently having scented the feast through their maze of underground passages. All were trying to tear off a bite by clamping onto the bird and spinning. Mercifully, darkness soon obscured my view of the multiple serpentine writhings, but the sound of them continued deep into the night.

Three species

There are three species of freshwater eels in French Polynesia. The large estuary eel is the giant marbled eel (Anguilla marmorata) which inhabits the larger rivers below the waterfalls.

The mountain eel is the Polynesian long-finned eel (Anguilla megastoma). It is slender and serpentine, and inhabits the narrow and elusive waterways higher up.

The third species is the Pacific short-finned eel (Anguilla obscura). It is uniformly dark in colour with a white ventral surface and tends to inhabit more stagnant regions upon the coastal plain and the pools of streams deep in the valleys. It distinguishes itself from the other two, it is said, by eating insects and molluscs instead of shrimp and fish. However, I found them all to be more opportunistic than that, and to eat whatever they could grab.

Life cycle

The life cycle of eels is one of the most remarkable things in the biosphere. They hatch in special places in the ocean and drift with the currents, nibbling on plankton and other microscopic bits and pieces. When tiny, they are transparent and are called glass eels. They become elvers as they grow older. After a long migration, they arrive at the rivers and streams from which their parents originated, and by then, they are large and strong enough to swim upriver until they find a suitable place to pursue their lives.

The eels of Polynesia live only in the fresh waters of a few Pacific Islands and the place where they mate and spawn is not known for sure but is thought to be to the east of Tahiti, or between Samoa and Fiji.

Australian freshwater eels live in mountain streams as high as 1,200m in elevation and travel from all across the eastern coast of Australia to mass spawning events near New Caledonia. The offspring spend about two years growing before returning, as elvers, to the river where their parents lived. On the full moon of March, they leave the sea and swim hundreds of kilometres upriver, breaching obstacles (including waterfalls and cliffs) to reach their destination, where they live for many years before migrating back to the place where they hatched, to breed.

The freshwater eels of both North America and Europe spawn in the Sargasso Sea and travel with the Gulf Stream to their respective continents. All over the world, local eels have their own migration routes, many of which are yet to be discovered.

The giant marbled eel

While exploring the rivers, I met several giant marbled eels. One small one would zigzag forth from a pile of rocks some distance away to confront me each time I passed. He set himself down in front of me and gazed. Then, he would raise his lip, as if snarling.

On one of my approaches to the river, there was a spectacular water lily in a little backwater, and each time I passed it, I stopped to admire it. It was just as dramatic beneath the surface. One day when I went underwater there, beneath those shading leaves, a huge eel was entangled.

I raised and snapped the camera instantaneously, and at the same moment, he exploded into action and raised a screen of mud. His bulging eye looked about as astounded as I was. I always looked for the water lily eel when I passed through that pool, and found him in a variety of places, even hanging in the greenery.

But I was never able to learn more about the behaviour of these strange fish. Even the ones who encountered me many times did not interact at all. They only came forward and made eye contact. Likely, they were ready to defend themselves in case I should attack. Sadly, these mysterious animals have been fished unmercifully until they have disappeared completely from large regions of the world. ■

Go to part one in issue #103 here >>>

Ethologist Ila France Porcher, author of The Shark Sessions and The True Nature of Sharks, conducted a seven-year study of a four-species reef shark community in Tahiti and has studied sharks in Florida with shark-encounter pioneer Jim Abernethy. Her observations, which are the first of their kind, have yielded valuable details about sharks’ reproductive cycles, social biology, population structure, daily behaviour patterns, roaming tendencies and cognitive abilities. Please visit: ilafranceporcher.wixsite.com/author.

REFERENCES:

Johnson, Richard H. (1976). The Sharks of Polynesia. Les Editions Du Pacifique.

Bshary, R., W. Wickler and H. Fricke. (2002). Fish cognition: a primate’s eye view. Anim Cogn 5:1-13