Underwater photographer Peter Verhoog of the Dutch Shark Society is on a mission—a mission to save sharks. He wants to raise awareness for sharks and their fate among a wide audience. One of the ways to do this is to show people not only the beauty of sharks but also shark behaviour and their sometimes worldwide migration and feeding patterns.

Contributed by

Marine conservation is almost never a national matter; migratory species can cross many borders, and regulations have to span more than one nation to protect a species. The whale shark is a highly migratory and cosmopolitan tropical and warm temperate species. It is established that the whale shark occurs in an astonishing number of countries—124 countries worldwide.

This shark is the world's largest fish, with a maximum recorded length of 16 meters and a mouth that can be 1.5m wide. Its life cycle is poorly understood. Populations appear to have been depleted by targeted harpoon fisheries in Southeast Asia and perhaps incidental capture in other fisheries. Its flesh is eaten, but their fins are more valuable; in the markets in the Far East, one fin from a whale shark can sell for over US$ 15,000, the total from one single shark can exceed US$ 60,000. Its normally low abundance make this species vulnerable to commercial fishing.

Why tracking?

Whale sharks have become a species listed as "vulnerable" on the IUCN Red List. Its life history is largely unknown. Tracking individual sharks is therefore a valuable practice, being it by photo ID or tags.

In 2012, Peter Verhoog visited Djibouti, a true 'hotspot' for juvenile, predominantly male whale sharks. From mid October to February, plankton blooms develop in an enclosed bay near Djibouti town called the Goubet al Kharab (Devil’s Cauldron). This bay is visited by whale sharks year round, but the number of shark is much higher during the plankton bloom. This aggregation has been studied for a number of years, and confirms that whale sharks aggregate in certain areas rich in nutrients to feed on seasonal aggregations of tropical krill and bait fishes. They just follow their food, and depending on the type of plankton, the numbers rise and fall.

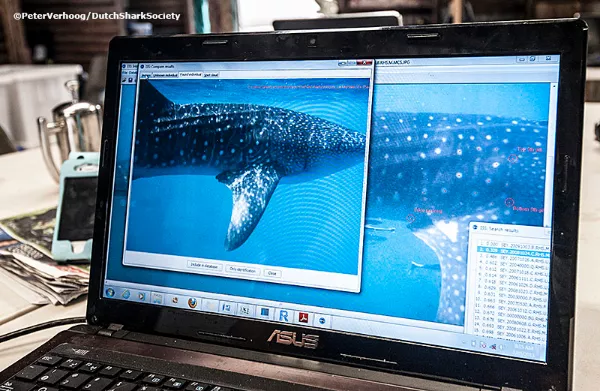

A team of volunteers snorkels with the sharks, and supports the research team of the Marine Conservation Society of the Seychelles to identify sharks by taking photos of the spots on their left and right sides. These spots are like fingerprints, and every shark has a unique pattern that can be identified with special matching software. All other markings, like scars, are documented as well. It is also noted, which fish species accompanies the whale shark, as this gives an indication about the route they have taken—close to reefs, or through the open ocean.

Conservation photography is different

For a conservation photographer, it is just not ‘done’ to interfere with research. The latter is the most important part and main goal of any research expedition, and contrary to any 'tourist’ expedition, the photographer is the last in line to approach the animals. And you have to work incredibly fast, as the last person to approach an animal, you are very often confronted with just the tail.

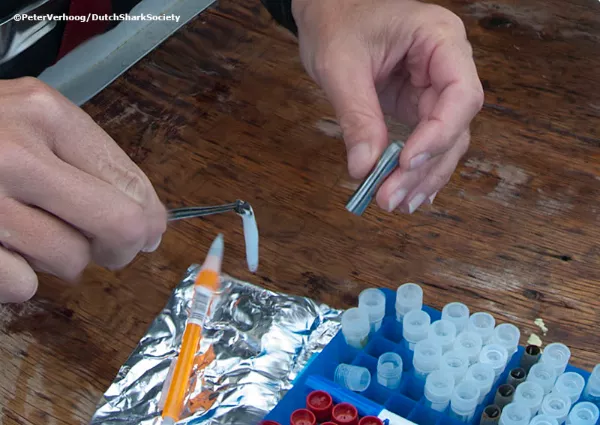

It was an exciting trip, with large numbers of whale sharks—391 in the first week, 319 in the second week and 370 in the third week. The research team also fished for plankton, took ID pictures and skin samples and tagged a number of sharks. Verhoog documented all procedures, and all his pictures can be used freely by researchers, students and non-profit organizations.

Moving on to Australia

In April 2013, Verhoog joined doctor Mark Meekan of the Australian Institute of Marine Science on his yearly trip to Ningaloo Reef, another whale shark hot spot. Adult whale sharks turn up at Ningaloo every year from about March through to the end of July.

But where do they go afterwards? Meekan is determined to find out. He has been attaching tracking devices and cameras to the whale sharks, which have revealed some startling facts.

During his research, a spotter plane searches for whale sharks, and informs the team about their location. Tag data has revealed that whale sharks seem to head out in different directions. Some go to Southeast Asia, others swim up north to Indonesian waters, and some head for the open ocean. During their journeys, whale sharks can travel 30 kilometers a day and make deep dives to over 1,000 metres.

And one tag, attached at Christmas Island in 2008, was even collected at the home of a fisherman, who found it collecting turtle eggs on a beach and had taken back to the village. Thanks to Google Earth, an assistant of Mark Meekan paid him a visit and collected the tag. It was probably ripped off by a predator. ....

(...)

Published in

- Log in to post comments