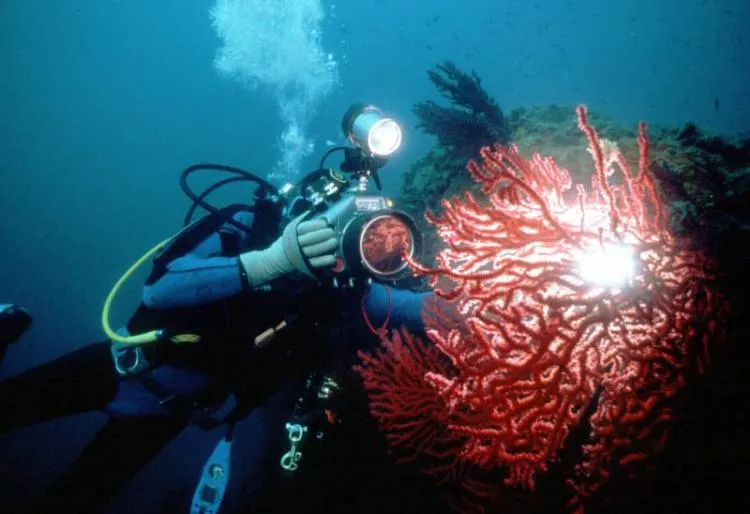

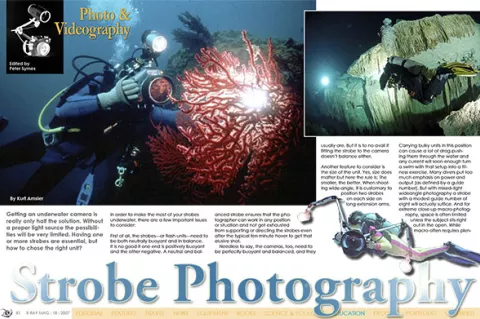

Getting an underwater camera is really only half the solution. Without a proper light source the possibilities will be very limited. Having one or more strobes are essential, but how to chose the right unit?

Contributed by

First of all, the strobes—or flash units—need to be both neutrally buoyant and in balance. It is no good if one end is positively buoyant and the other negative. A neutral and balanced strobe ensures that the photographer can work in any position or situation and not get exhausted from supporting or directing the strobes even after the typical ten minute hover to get that elusive shot.

Needless to say, the cameras, too, need to be perfectly buoyant and balanced, and they usually are. But it is to no avail if fitting the strobe to the camera doesn’t balance either.

Another feature to consider is the size of the unit. Yes, size does matter but here the rule is: The smaller, the better. When shooting wide-angle, it is customary to position two strobes on each side on long extension arms. Carrying bulky units in this position can cause a lot of drag pushing them through the water and any current will soon enough turn a swim with that setup into a fitness exercise.

Many divers put too much emphasis on power and output (as defined by a guide number). But with mixed–light wideangle photography a strobe with a modest guide number of eight will actually suffice. And for extreme close-up macro-photography, space is often limited unless the subject sits right out in the open. While macro often requires plenty of power, this can be achieved with two smaller units—it actually enables you to obtain a better colour reproduction.

TTL or manual exposure?

It would be silly not to use automatic strobe exposure control (TTL) for macro, close-up or with lenses covering angles up to 60°. For wider angles, especially with super wide-angle lenses, strobe exposure is influenced by a number of factors, and TTL exposure would not be appropriate. This is easily understood when looking at the way automatic strobe exposure control works.

Light emitted by the strobe is reflected by the subject and measured either in volume or speed, dependending on the TTL system built into the camera electronics. This enables the camera to control the strobe for accurately exposure. This works well when our subject is well defined in space and distance as is usually the case when working at close to medium range. However, when working with a wide-angle lens, we have a different situation.

Other than our main subject, there will be a heck of a lot of other stuff in the frame. The exposure program can’t tell whether the light it measures is being reflected off what’s important or off a part in the frame that’s unimportant but closer to the camera. Also, most the time, an open water backdrop surrounds our subjects as well. So, if the subject does not fill more than 70 percent of the frame, there will not be sufficient reflection for proper metering. Exposure errors are quite common when not bearing this in mind. For wide-angle photography, it is therefore advisable to use manual exposure taking into consideration existing light.

Mixed light photography

Often photographers forget that—thanks to the great big diving light in the sky—they have daylight at their disposal as well. We use it to show more in our pictures than the strobe can illuminate. For optimum effect, we mix the two sources of light highlighting elements in the foreground and emphasizing their colours by flash, while ambient light generates depth in the background where the strobe light can’t reach.

Amsler’s Formula

To achieve consistent results apply “Amsler’s Formula”: AS + EA (aperture as

per strobe + exposure time as per available light). Any strobe, whether of the

dry or wet variety, dictates a specific aperture setting. With the aperture given, we are then left to control exposure of the background by varying shutter speed.

Consequently, the photographer has to measure the ambient light first to find out which shutter speed matches the aperture setting dictated by the strobe unit for a correct exposure of the background. This is easy using the camera’s built-in light meter.

Some cameras and housings even allow the photographer to switch from spot metering to integral or matrix metering! Spot metering often gives you better information and an impression of the lighting conditions simply by pointing the measuring spot around and taking measurements.

To enhance colour contrast, we are aiming at having our backgrounds reproduced slightly on the dark side. So, we don’t point the camera directly at the main subject while we measure the light. Instead, we aim high—approximately in a 30° angle up towards the surface.

This metering might, just for as an example, indicate that a shutter speed of 1/30 will match the set aperture of f8 (as dictated by the strobe) so that is where you put the camera’s setting. The slow shutter speed will allow for sufficient available light to expose parts of the film representing the background and gives us the rich, dark, blue water background we are after. The strobe that illuminates the foreground isn’t affected by the shutter speed as the flash goes off much faster—it is only controlled by the aperture.

After some practice with a light meter, the photographer will soon develop the ability to “read” the ambient light. (S)he is then capable of working out the correct mixed light exposure time from experience for any depth or situation.

10 Tips

- Most important, the strobe needs to be buoyant and perfectly balanced so you are able to work in any position. A buoyant strobe can be easily aimed at the subject because it can be moved in any direction without releasing the joints of the strobe arms.

- Remember that in wide-angle photography the position of the strobe is very important to avoid backscatter and to gain an uniform illumination of the subject. You have to take into account that the larger the picture angle, the further the strobes have to be positioned away from the lens!

- Analogue , I-TTL or E-TTL are great inventions, but you have to know how to use them. In macro and close-up photography, problems rarely occur. Using TTL in wide-angle photography, on the other hand, is often tricky, any foreground or a incorrect strobe position can result in under or over-exposed pictures. I recommend using manual flash mode for wide-angle.

- Due to refraction, all subjects underwater appears to be closer than they really are. Consequently never aim your strobe at the apparent distance in which case too much light will hit the foreground and illuminate the water between camera and subjects. The results are diffuse pictures, overexposed foregrounds and backscatter. Aim the strobe always over the subject, or next to it, if using two strobes. The best option is to have a focusing light inbuilt or fixed on each strobe.

- Take good care of your strobe connectors. Unplug them after a day of diving and clean the tiny O-rings. Be careful when you unplug them so no saltwater or grease get in contact with the pins. Clean the pins regularly with alcohol.

- Going on diving holidays... always bring a spare sync-cable with you. Modern strobes are powered with regular batteries. I recommend using rechargable batteries of 1500 ma as they recharge the strobe capacitor much faster.

- As a back-up, in case of electical problems on a dive boat or other unforeseen events, always bring a pack of regular batteries with you.

- Using full power strobe in murky water has the same effect as using long lights when driving in a fog. You just illuminate particles. Serious photographers, therefore, power the strobe power down in response to reduced visibility—the murkier, the less power.

- Reducing power is only possible in manual mode, by switching to ½ or ¼ power.

- Perhaps you were wondering about the white diffuser cap most manufactures deliver with the strobe unit. It has the effect of making the light softer, warmer and reduces the light output by one f-stop. Use it in murky water to gain less backscatter and also if you take pictures of people in indoor pools or at close distances in general. It renders skin tones warmer, and therefore, more appealing in the picture.

- Never forget to consider the ambient light besides that of your strobe! Mixing the two light sources will change the “common” black background in macro as a matter of choice, but it is a must in wide-angle to show more in the pictures as the strobe can illuminate. Use “Amsler’s Formula”: AS + EA as it is explained in the main text.

- Due to the distance the light has to travel through water, the colour temperature of the strobe plays a big role if your subject will appear in their original colours in the picture. Macro strobes have 5600° Kelvin and cannot be used for wide-angle because the light is too cold (blue tint).

Wide-angle strobes have 4900° to 5200° Kelvin and are therefore too warm (reddish) for macro. To modify your wide-angle strobe for macro photography, you can add a light blue foil on the strobe. It is a compromise, but better than having yellow anemones reproduced as orange. ■