As more and more people get their dive news and articles digitally, print dive magazines have been disappearing. Freelance photojournalist Eric Hanauer looks back at his time as a dive writer over the decades and how dive journalism has evolved.

Contributed by

How do you get your news in the morning? Radio? TV? Internet? I’ll bet it is not through the newspapers. Print publications are on life support.

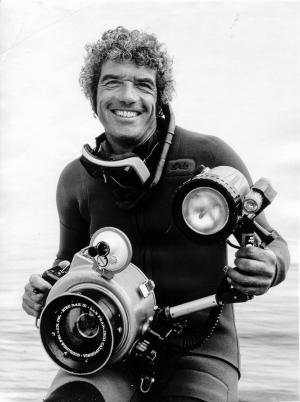

That was not easy to write. For 47 years, I was a freelance photojournalist, published in dive magazines internationally. Most of that coincided with the golden era of specialty publications, from the 1970s into the early 2000s. The pay ranged from adequate to good, but I had a day job at California State University, Fullerton. That allowed three months in the summer and six weeks over the new year holiday for travel assignments. It was an exciting lifestyle that led to many adventures and some hassles. I would like to share some of that with you.

The genesis of my career occurred some 25 years before my first published article. I was the swimming coach at Morgan Park High School in Chicago. A slight freshman, Dan Rittschof, tried out for the team. He was too small and too slow to be a swimmer, so I suggested he try springboard diving. Within a couple of years, thanks to his talent and outside coaching, he became the city champion.

A quarter of a century later, I was giving a presentation at another California university. A bearded post-doctoral student came up afterward: Dan Rittschof, PhD. He informed me that his sister, Bonnie Cardone, had just been hired as editor of Skin Diver magazine. A couple of my friends, Mike Curtis and Dave Bewley, had recently discovered the wreckage of a World War II Corsair fighter plane in the waters off Laguna Beach. I pitched an article to Bonnie, and she bought it.

My ego was so fragile at the time that if my pitch had been rejected, I might never have tried again. But now, I had an article and photos published in the world’s largest dive magazine—at US$35 a page. Rejections eventually came, but by that time, I was prepared to move beyond them.

Advertorial approach

Skin Diver was often criticized for its advertorial approach. I admit to having been part of that process. Among my initial assignments were equipment reviews. Bonnie advised that if I did not have something good to say about a product, to not say anything. That was put to the test when a product from a reputable company simply did not work. They sent me two more copies of the same item, but the results were the same. The article was canceled.

On another occasion, I was asked to review the Aqua Vox, a plastic funnel-like device that substituted for a regulator mouthpiece. Its purpose was to allow divers to talk to each other underwater. There were two problems: 1) It did not work any better than talking into your mouthpiece; 2) It leaked.

When I explained the problems to Bonnie, she replied that the company had bought six months of page-two advertising. I declined to write the article. So, the publisher took over. He did a great job of dancing around the issues, merely describing the product, never saying whether or not it worked. Within a few months, Aqua Vox was out of business.

For about a year, I was assigned to review inflatable boats. I was not a fan of being bounced and splashed, but by this time, the page rate had improved. Eventually, the writer who reviewed regulators got tired of his gig, so we traded. This was more like it. I obtained a tank with a Y-valve and attached my own regulator to one side as reference, and the test unit on the other. I compared breathing effort, shallow and deep, in different body positions, while swimming hard, along with the ease of clearing and other additional tests.

Dive travel

Travel assignments were my favorites. I would sometimes be paired with an advertising sales rep. We would be wined and dined, and flights and diving were free. What’s not to like?

On one of the trips, the rep and I were in southern Baja. He was driving our rental car too fast for safety, on the dark, narrow roads. One evening, we came upon a van that had turned on its side and landed off the road. Inside were two people, semi-conscious and bleeding. Until the authorities came, we gave first aid and reassurance. The rep drove more slowly and carefully afterward.

Oceans magazine

Bonnie Cardone was a great editor. Among the most significant pieces of advice that she gave me was, “The way to be valued here is to write for other publications.”

One of my first was Oceans. An opportunity arose to join an expedition of the deep-sea submersible Alvin, off the coast of California. The purpose was to examine the effect of a whale carcass on the bottom-dwelling community. There was no chance for me to be onboard the Alvin; that was limited to working scientists. But I did get permission to follow Alvin down and shoot photographs. Alone. That could never happen today.

As the submersible descended, I began shooting. It did not take long for the water below to turn black, and Alvin looked like a colorful toy. By that time, I realized it was time to ascend. This was before the advent of computers, and I did not check my depth gauge. What I did know was that any dive on the US Navy tables over 190ft required a five-minute deco stop.

So, while hovering at ten feet, I looked inside my camera housing, and saw a small puddle through the viewing port. The housing was a cylindrical Niko-Mar, with the camera about three inches above the bottom. As the minutes slowly ticked off, and the puddle kept growing, I decided my body was more important than the camera. When the five minutes finally ticked away, I surfaced and admonished the crew to keep the housing perfectly upright. There was less than an inch to spare, and some publishable images inside.

Scubapro Diving and Snorkeling magazine

In the 1980s, Scubapro launched their own magazine, Scubapro Diving and Snorkeling. The pay was good, so I wanted to climb aboard. The first question CEO Dick Bonin asked was, “Can you write anything besides puff pieces?” He must have become convinced I could because they kept giving me assignments.

When they celebrated the company’s 25th anniversary, I wrote the lead article, as well as three others in that issue. The editor, Ed Montague, called and asked me to use a pseudonym, so it would not look as though the issue was done by one writer. It did not take long for me to come up with Clark Addison. Bonin, an ex-Chicagoan, instantly knew the connection. Wrigley Field, the Chicago Cubs’ ballpark, is located at the corner of Clark and Addison Streets.

On occasion, I was able to combine my scuba and baseball passions. A friend introduced me to Steve Green, the Cubs’ team photographer. It turned out that Steve was a casual diver and his wife, Lisa, had been a dive guide in the Caribbean and in Thailand.

He got me a pass into the photographers’ well at Wrigley Field, and I had the opportunity to shoot some games alongside the pros. That resulted in a Skin Diver article featuring Steve and a comparison between sports photography and underwater photography. For the next 19 years, I shot occasional Cubs games, and even got some images into their in-house publications. I also bled for the Cubs, having been hit in the chin by a foul ball, resulting in five stitches.

Advertising copy and books

Some of the best paying gigs did not include a byline. During the Scubapro days, I was asked to write some advertising copy. That may have been easy for Mad Men, but one paragraph usually took more time and effort than a full article. Later, I wrote the copy for two editions of the Scubapro catalog. That was like writing a book.

Just before the pandemic, Aqua Lung commissioned a coffee table book to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the invention of the Gagnan-Cousteau regulator. I assembled a team with my wife, Karen Straus, as editor, and Bonnie Toth as graphic designer. The project consumed us for most of 2017 and included trips to France and Italy for interviews.

The hardcover, boxed edition was subsequently translated into German, French and Italian. Although it paid better than my other four books combined, it was never released to the public. The book, entitled Immersion, was a corporate gift for executives, clients and VIPs connected to the company.

The Red Sea

My first Red Sea trip came a few months after the Sinai Peninsula was returned to Egypt in 1982. Sinai was starting all over after the Israelis left. Hani el Meniawi, who had married an American and lived in California, had plans to sell Egypt travel to American divers. One of the keystones would be a guidebook. That was where I came in.

Hani, in conjunction with the tourist office, arranged for me to spend the next few summers traveling around the country. Dive boats were rickety, wooden fishing boats powered by two banger diesel engines. Accommodations were not luxurious.

Sometimes, Hani boarded me with friends and relatives, sometimes with fishermen. That turned out to be a blessing, because instead of the tourist experience, I got to know the country from the inside. I even learned some rudimentary Arabic.

One evening, we were on a boat, anchored off Marsa Bareka. The desert wind whipped the nighttime temperatures over 100°F, and nobody could sleep. So, the dive guides spent the night teaching me essential, imaginative Egyptian swear words. I use some of them to this day.

The Egyptian Red Sea book had a long, painful gestation. Richard Stewart, the founder of Sport Diverand Ocean Realm magazines, was planning to publish it. He was on shaky financial ground, and after a couple of years, had to bow out. Herb Taylor, publisher of a series of dive travel guides, picked it up. But he and his wife died in a private plane crash.

Finally, Ken Loyst, publisher of Discover Diving magazine, delivered the book in 1988. I would like to say it sold thousands of copies and made lots of money. But that is not reality. On the other hand, a book grants the author more credibility than dozens of magazine articles. Following its release, assignments became more frequent and desirable.

When we dived the Brothers Islands in the Red Sea in 1983, fewer than 50 divers a year had been there. Now, there are a hundred on a typical summer day.

Cabo San Lucas

A similar pattern was seen in Cabo San Lucas. Six friends and I made our first trip there in 1973, three months after the road was paved. We drove down in camper vans, slept on beaches and open fields, and brought an inflatable boat and a small compressor. Our only reference was a tiny map, printed on the sports page of the Los Angeles Times.

That first trip ended tragically when a teenage boy, whom we had just met that morning, died in a failed buddy-breathing attempt with his father. It happened in the canyon at Cabo. We attempted to do CPR on him on the way to the city’s small hospital. After that, the joy of discovery turned to weary resignation.

Sipadan

Another friend, Charlie Gibbs, sent me to Sipadan a year after it opened to diving. There were ten divers on the entire island. I returned a year later, and there were twenty. It seemed crowded.

I had been pursuing a cover shot at Skin Diver, and finally succeeded. A resident school of barracudas always hovered in the water column at Barracuda Point. As I was lining up a shot with my Nikonos 15mm lens, a sea turtle swam into the picture. Click.

Another feature of Sipadan was Turtle Tomb, a cave with a shallow entrance where turtles entered, got lost and drowned. Several skeletons remain inside. No matter how far in you go, there is a tiny pool of blue light indicating the exit. I was granted permission to go in any time and shot some dramatic images without other divers fouling the visibility. Like the Alvin dive, that approach would not fly today.

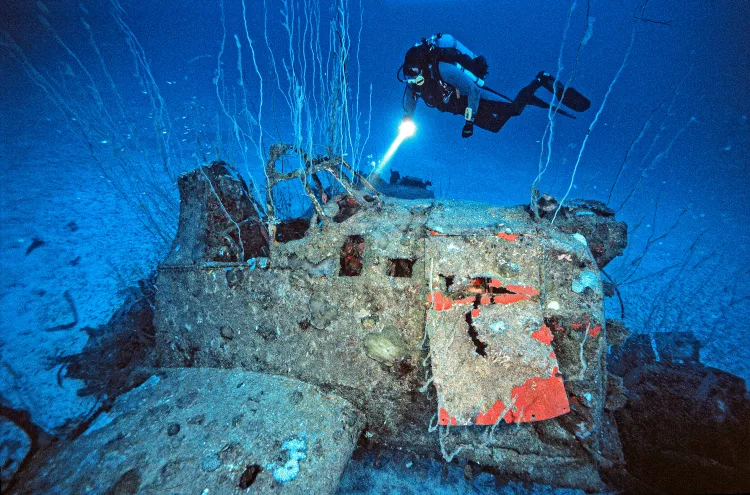

Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll was the site of US atomic bomb tests in the 1940s and 50s. Even after the Marshall Islands were granted independence, US Department of Energy divers continued to study the wrecks for several years. That kept them safe from looters.

Before it opened to sport divers, the Bikini Council consulted with cave and tech diving experts. Brazilian instructor Fabio Amaral put their ideas into practice, leading the fledgling operation for over half a decade. When it opened, I was invited to write about the first trip.

The publisher of my magazine wanted to come along, but could not make that date, so we delayed a week. Arriving on the airstrip at Bikini, I was greeted by the editor of a rival magazine, who had just scooped us.

Nonetheless, Bikini remains among the most memorable experiences of my diving career. I made four trips there between 1996 and 2006, covering the entire era of the land-based dive operation. Today, only technical certified divers on a liveaboard can go there.

At Bikini, divers touch the face of history. Unlike World War II sites that have primarily tankers and freighters, Bikini has warships. The aircraft carrier Saratoga was Admiral Bull Halsey’s flagship. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto launched the attack on Pearl Harbor from the deck of the battleship Nagato. Additionally, there are destroyers, submarines and cruisers.

What makes things difficult is depth. The bottom ranges from 170 to 180ft. The shallowest dive is the deck of Saratoga at 100ft. Typically, we would make a deep dive in the morning, 35 minutes at 170ft, followed by an hour of decompression on 75 percent oxygen, supplied from the support boat at 30, 20 and 10ft. Afternoon would be penetration diving on the Saratoga, at 130 ft with the same deco protocol. Deep dives were made on air, with twin tanks.

There was international interest in Bikini, so I was able to recycle articles for magazines in other countries. When necessary, they handled translation. Eventually, additional articles found second homes in England, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, France and Israel.

Micronesia

At that time, I was writing my second book, Diving Micronesia. That began when Bill Acker, founder of Yap Divers, pulled me aside at the DEMA show. He had seen my Red Sea guidebook, and suggested I write one on Micronesia. “Get me out there and I will,” I replied.

Bill was as good as his word. He arranged passes on Continental Airlines, housing and diving on all the islands from Yap to the Marshall Islands. I spent three memorable summers bouncing around the Pacific, learning about the culture, World War II history and its underwater world. Meals often consisted of sashimi, because it was the cheapest thing on the menu, and the fish had probably been swimming that afternoon.

Downsides

Not all travel was fun. I was hired as a dive guide on an eco-cruise ship, from Easter Island through French Polynesia to the Cook Islands. Thinking that this could lead to a good article, I began keeping a detailed journal. By the fourth day, I realized nobody would publish it. Everything that could go wrong did. But I kept on writing.

Soon afterward, Bret Gilliam began publishing Fathoms Magazine. He had the guts to run the article. I changed all the names and wrote it with a light, satirical touch. That turned out to be unnecessary, because shortly after, the cruise line went out of business.

Profiles of dive pioneers

I had always been interested in origins and history. When people like Chuck Nicklin, Jim Stewart and Andy Rechnitzer talked about the old days, I was an avid listener. When Dr Wheeler North was retiring from Caltech, I asked to write his story.

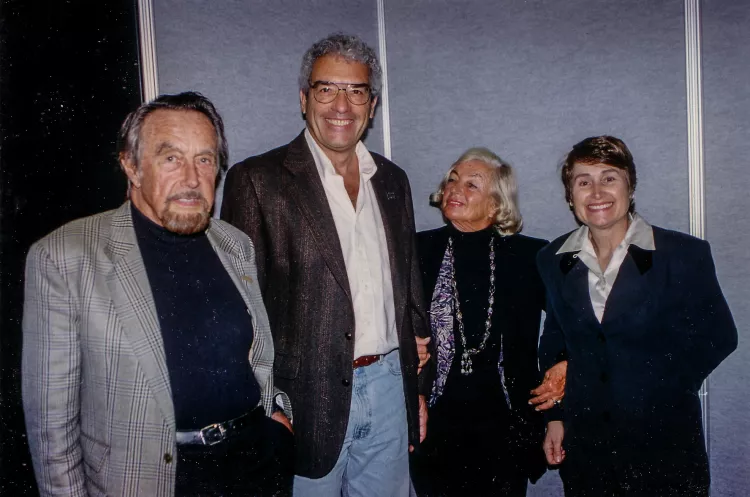

After El Niños decimated southern California kelp forests in the 1950s, North developed a technique of transplanting healthy kelp from other areas. Discover Diving published the article, which eventually led to a series of interviews with pioneers. Among them were Zale Parry, Dick Bonin, Bob Hollis, John Steel and Tom Mount. They were eventually compiled into my third book, Diving Pioneers. After publication, I was able to reel in a few more historic fish: Lloyd Bridges, Commander Doug Fane, and the ultimate pioneer, Hans Hass.

Interviewing

The key to a good interview is to be prepared. Do your homework on your subject, and do not ask stupid, obvious questions. For the most part, I was confident, but there were a few whose intellect was so far beyond mine, that I was treading on shaky ground. Among them were Hans Hass, Dr Hugh Bradner (inventor of the wetsuit and a Manhattan Project scientist), astronaut Mike Gernhardt (a former scuba instructor and commercial diver), and Bruce Wienke, a Los Alamos physicist who developed the algorithm for the Atomic Cobalt dive computer.

For the Gernhardt interview, I traveled to NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Lab in Houston. I tried and tried to gain permission to dive in the gigantic pool and shoot my own images, but the NASA bureaucracy was impenetrable. They did assign one of their divers to shoot photos and allowed me the run of the deck.

To top it off, Gernhardt invited me to the launch of his fourth shuttle mission, STS 104. We sat in the VIP section; the only ones closer were the astronauts. The 1 a.m. launch turned night into day, and I could feel the rumbling of the rocket deep within my chest. Even though I never got into the water, and had to spend my own money, it was one of my all-time favorite assignments.

When Skin Diver celebrated its 50th anniversary, they asked me to write the history of the magazine. By then, it had been bought and sold, and kept sliding down the new owners’ priority lists. Publication ended a year later, in November 2002. My article on Cuba was the cover story in the final issue.

A golden era

Sometimes, when photojournalists from that era get together, I would say, “We sure came along at the right time.” We did not make much money, but the world was full of opportunities. Companies in the dive travel industry had connections and dollars to spend on coverage.

Richard Stewart had a deal with Pan Am, leading to the most memorable flight I had ever been on. First class. Polar route. Sport coats and ties were required when boarding the plane but could come off in the air. There were more flight attendants than passengers, as we were wined and dined from Los Angeles to Frankfurt (en route to Cairo). It was a midsummer day, and the highlight was watching the setting sun barely kiss the horizon over Greenland.

At the time, Pan Am was the world’s premium airline. Some others did not quite measure up. One Middle Eastern carrier sold the flight attendants’ emergency seats—to smokers. On another, a flight attendant handed me a small bottle of wine as I entered the first-class cabin. When I finished my meal, she took away everything except the wine bottle. She said, “You throw it away. I don’t touch that stuff.”

Then, there was the time I was in the airport bound for Malaysia, I encountered a small group of airline pilots going to the same destination. What could be better than first class? How about a 747 cockpit? When they were invited in, they brought me along. Flying certainly was better before 9/11. But you knew that.

Acknowledgements

None of this would have been possible without the support of two great women. When I married Mia Tegner, a marine biologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, I realized that unless I achieved something, I would be known as Mr. Mia. That kicked the writing career into high gear. In addition to being a wonderful dive and travel buddy, she taught me to thoroughly research what I wrote. Mia tragically died in a diving accident in 2001.

Shortly afterward, Karen Straus paid a condolence call. She had been a dive buddy in the 1970s but moved out of the area for over 20 years. With a long history in photojournalism, Karen was a published writer before I was. We married in 2004 and share a passion for many of the same things: diving, cars, photography and our cat, Teo. Both Karen and Mia have been elected to the Women Divers Hall of Fame.

In addition to Bonnie Cardone, I was fortunate to work with some wonderful editors and publishers: Cathryn Castle, Mark Young, Tony Bliss, Cathy Cush, Bret Gilliam, Stephen Frink, Ed Montague, Ken Loyst, Steve Blount, Fred Garth, Peter Vassilopoulos, Phil Nuytten, Ty Sawyer and Al Hornsby.

Concluding thoughts

What have I learned in 47 years? Here are five takeaways:

1. Always meet deadlines.

2. Rewrite. Rewrite. Rewrite.

3. Check your sources.

4. When something is told to you off the record, keep it that way.

5. Have a day job to fall back on.

Looking back, it has been a long, strange trip. Among the more than a dozen North American print magazines I wrote for, only two survive. Sometimes, I feel like Forrest Gump, blundering my way through history. Would I have changed some things? Of course. But dive journalism has brought a lifetime of experiences that I could not have envisioned when Dan Rittschof tried out for the Morgan Park High School swim team decades ago. ■