When it comes to responding to certain computer alarms, can one be too cautious? Being well informed about gas exposure limits and computer defaults can be an advantage. Simon Pridmore discusses a case in point, involving computer nitrox alarms on a routine wreck dive

Contributed by

The other day, I joined a group for a dive on a small shipwreck, lying on a sandy plain just beyond a reef wall in the central Philippines. We were briefed that the site itself did not have much to recommend it. Recent coastal development had led to runoff and consequent coral destruction, and unsustainable fishing practices had taken care of most of the large schools of fish in the area.

However, from a marine life point of view, the wreck was an oasis in the desert, and that was why we were diving there. The interior was packed full of bait fish, and there were plenty of predators around—such as catfish, moray eels and leaf scorpionfish—to take advantage of the prey. We were also advised to keep our eyes peeled for a photogenic red clown frogfish, and there would be cleaner wrasse offering their services to any passing animal with an itch, as well as a small school of blue-lined snapper circling around us. So, we could expect lots of activity. It all sounded very good.

The dive

The dive guide did not lie. As we approached, even from a distance, one could see the wreck was jumping with life, as opposed to the surrounding reefscape, which was as dismal as we had been warned.

My buddy and I hung back a little from the group and watched the rest of our gang drift in to the site. Then, there was a beeping sound, swiftly followed by more beeping. Suddenly, half the group started looking at their wrists rather than the wreck, there was a general onset of anxiety, and then they were gone, swimming quickly back to the reef wall, where they spent the rest of the dive searching in vain for something interesting to photograph and ended up ascending early.

After the dive, these divers surrounded the guide, complaining that the dive had been a waste of time. Meanwhile, the few of us that had stayed on the wreck were quite happy. There had been plenty of action there to keep us entertained.

Misplaced concern

I already had a good idea of why half the group had chosen not to stay on the shipwreck and departed so quickly, but I had to ask.

“One point four,” they replied. “My computer gave me a nitrox warning,” “I don’t want to die!” and “We were too deep!”

We were all using nitrox 32, and the wreck was lying at exactly 35m (115ft), sitting bolt upright on its hull, so its shallowest point was about 30m (100ft). As the divers started swimming around it, they got close to a depth of 34m, their partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) reached 1.4, their computers’ nitrox alarm went off, and their immediate reaction was: “An alarm means danger. Let’s get out of here!”

They were acting out of concern for their safety, even though their retreat would cause them to miss out on the best part of the dive. This, of course, is all very admirable in terms of diving priorities in general; although, in this case, you could argue that their concern was misplaced and the degree of caution they were exhibiting was unnecessary.

An alarm means danger. Let’s get out of here!

Facts and figures

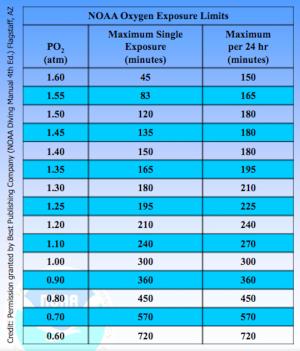

The chart illustrating this article should be familiar to all nitrox divers. If it was not shown and explained to you when you took your nitrox course, your instructor did a shoddy job.

Scientists and navy divers were diving with nitrox for decades before sport divers started using it. The science behind nitrox, including this chart, came to us via a former United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) diving officer named Dick Rutkowski. He started teaching nitrox diving to sport divers in 1985, after he retired from government service. Nitrox 32 was originally known as NOAA 1; nitrox 36 was NOAA 2.

The NOAA chart details the level of oxygen exposure at which a diver may be at risk of an oxygen toxicity convulsion. As you can see, the limits do not derive only from the pO2 a diver is breathing; they derive also from the length of time the diver spends exposed to that pO2.

Therefore, spending 150 minutes at a pO2 of 1.4 carries the same risk as spending 45 minutes at 1.6. But a pO2 of 1.6 is the absolute maximum for sport divers because, beyond this level, the permitted exposure time drops quickly to only a few short minutes. NOAA deliberately set conservative limits. After all, it did not want to lose its scientists.

When Rutkowski and others started teaching sport divers how to use nitrox, some people in the established sport-diving hierarchy feared that this was a dangerous thing to do. They prophesied that it would lead to mayhem, with nitrox divers suffering oxygen convulsions and drowning all over the place. This did not happen.

Today, millions of nitrox dives take place each year and it still does not happen. Experience has shown that sport divers diving on open circuit nitrox do not come to harm when diving within no-decompression limits and the NOAA oxygen exposure limits.

In any case, as one would expect, even in the beginning, the approach of the community of sport nitrox divers was conservative and instructors taught students not to plan their dive for a maximum depth where their breathing gas pO2 would reach 1.6, but to allow for factors such as defective gauges, defective analysers and diver inattention, and to not exceed 1.5 or so.

However, the early establishment fears did not go away completely and, as nitrox became more commonly used, the recommended maximum pO2 level for sport diving dropped from 1.6 to 1.4.

Computer manufacturers started establishing 1.4 as the default pO2 alarm level, and although the setting was user-changeable on many units, typically few divers ever bothered. This is still the case now and, in fact, some diver training agencies now teach 1.4 as the pO2 level beyond which one shalt not pass.

Moreover, the computer alarm is set to go off as soon as the computer calculates that the diver’s gas and depth equate to a 1.4 pO2. The concept of a diver being able to remain safely at a certain pO2 for a certain length of time seems to have been lost. The pO2 level is now all that counts, not the duration or the dose.

Hence, the misguided behaviour we observed among some of our fellow divers on the shipwreck dive.

Nitrox 32 was actually the perfect mix for that wreck dive. The water was warm. The visibility was excellent. There was no current and the divers had to expend only minimal effort on the dive, so there was no reason for any unusual level of concern. The maximum depth was 35m (115ft), giving the divers a maximum pO2 of 1.44, even if they were lying flat on the sand.

Also, with nitrox 32, their computers would give them a no-decompression time on and around the wreck of 20 to 25 minutes or so—far less than the 120-minute exposure limit that the NOAA chart allows for a dive at a pO2 of 1.5.

Sadly, it was completely unnecessary for the beeping divers to abort. They missed a great dive. What a shame that their misplaced fears got in the way of having fun!

It is good to be a conservative diver, but it is important to be well informed, so you can distinguish between being sensibly careful and excessively cautious.