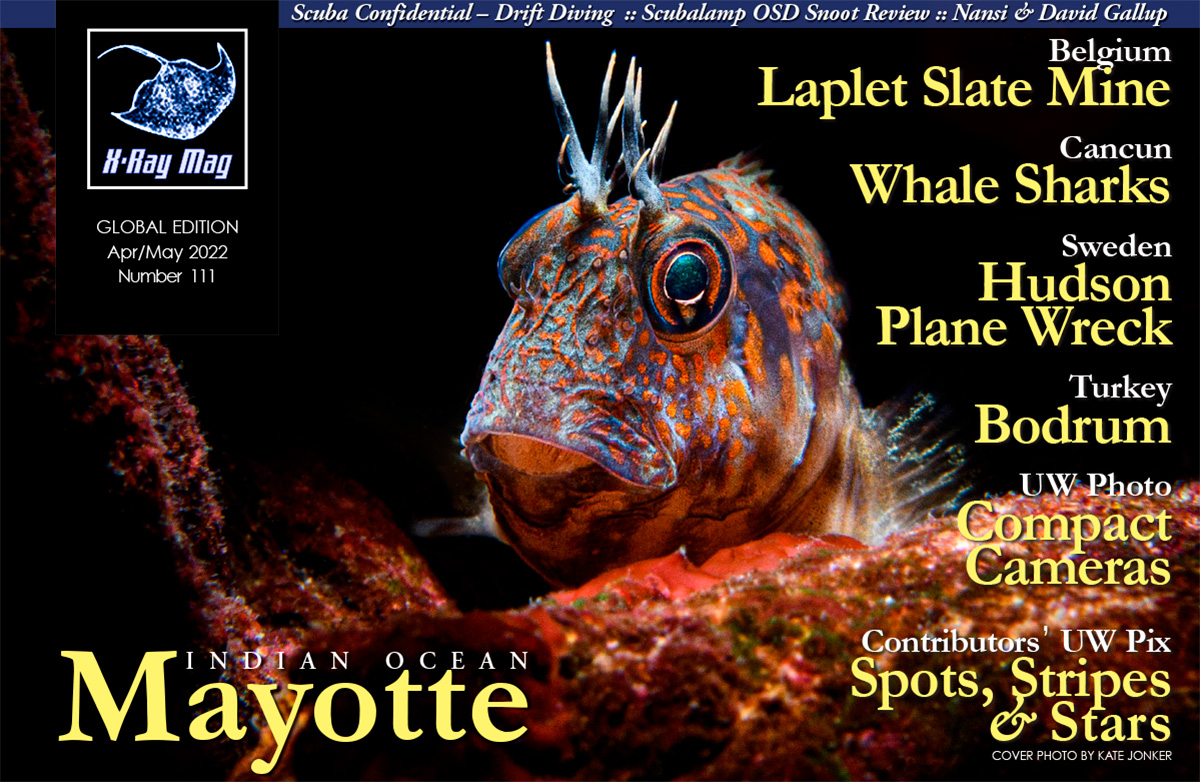

Some ocean animals are just inspiring. To be able to glimpse a massive animal like a whale shark can be a lifelong dream that some divers never get to experience. The ocean’s largest living fish inhabits all of the world’s tropical waters, but sightings are usually rare. However, there are a few seasonal hot spots where the likelihood increases. One of those hot spots is off the coast of Cancun and near Isla Mujeres and Isla Holbox, Mexico.

Contributed by

Sightings are almost guaranteed from June through to September when whale sharks congregate for unknown reasons in deep waters to feed. I had heard about this aggregation for years and finally found myself in the right place at the right time in Mexico. So, a dive buddy and I headed out for two days of snorkeling with the whale sharks.

What started off as a little-known event seen by offshore fishermen has turned into a very popular tourism experience. When the whale sharks show up, many boats stop whatever else they are doing (like fishing) and turn into whale-shark encounter boats. It used to be only a few boats taking people out, but now there are a lot more. As our boat neared our destination, it was obvious that we were in the right place because the horizon was filled with other small boats.

Regulations and safety

With such an influx of boats and people, there have been rules laid out to try and help protect the safety of tourists and (hopefully) whale sharks. All participants must wear lifejackets—a condition with which my buddy and I were a bit unhappy, both because they were sort of uncomfortable (we were quite confident in our ability to snorkel), and the bright orange lifejackets were going to show up in my photos.

Other rules included the following:

• No scuba diving

• Everyone must have a guide

• Only two people and one guide (per boat) are allowed in the water at a time

• There is a limit on the total number of people that can be in the water per whale shark

• No touching of the whale sharks

• No lights or strobe use

• Use reef-safe sunscreen only

I learned later that there is a way around the lifejacket rule if one is a certified freediver and on a charter carrying only freedivers.

Approaching whale sharks

With our legs dangling over the side of the boat, we were ready, geared up with masks, fins and snorkels in place. Looking down into the water, we could see the white spots and body outline of a whale shark next to the boat. We could also see nine snorkelers in the water next to it, who were slowly being left in the whale shark’s wake.

As I watched the boats, it looked like the captains maybe had a bit of a line-up system, allowing them to take turns. But just as this thought crossed my mind, I saw one boat jet out of “line” and cut off another boat, with the snorkelers’ legs dangling just like ours. For a second, I thought it was going to sideswipe the other boat (and the dangling legs). While it was a miss, I cringed inside at the unnecessary maneuver. What a jerk!

Looking up at what seemed to be a semi-organized group of boats, I suddenly saw what might be considered the other side of the coin. How did they go on like this—70-plus boats every day, with an average of eight snorkelers on each boat—and not run anyone over? Or smash legs on the side of the boat? Or hit a whale shark? It worried me.

Swimming next to a whale shark

But it was almost our turn to get into the water. Our captain got a little bit ahead of the whale shark, and we slid off the side of the boat, immediately kicking like mad to keep up with the giant creature. Words and images cannot describe the actual feeling of being next to such a massive animal (particularly one that does not want to eat you). For me, it was an overwhelming burst of happiness and joy just to be alongside a whale shark.

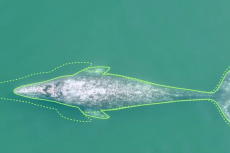

Whale sharks can grow up to 20m and weigh over 11,000 kilos; but the gentle giants only feast on tiny marine life like plankton, with their giant mouths gaping and stretching open, up to four feet across. They can swim as fast as 8kph, using a side-to-side motion with their whole bodies along with propulsion from their huge tails. We do not know much about their migration patterns, but records show that one tagged individual traveled over 8,000 miles in one year. The whale sharks’ blue bodies are covered in white spots, which are unique to each animal, like zebra stripes, making it sort of like a fingerprint for each animal.

Kicking as hard as I could to keep up with the whale shark, I could not help but also stick my head out of the water to look around for boats. It would be so easy for a boat to run over a swimmer. I realized the lifejacket rule probably helps immensely in preventing this. You cannot freedive in a lifejacket and surface in a different location, like under a boat propeller. Plus, the bright red or orange color of the lifejackets helps boat crews to better identify the small humans in the big, blue ocean.

After the whale shark outswam us, we eventually stopped, and our boat came around to pick us up. Wide smiles were on everyone’s faces, and we got back on the boat, ready to go again.

When it came to our turn again, my buddy and I were geared up and ready to go. Our boat was “in line” when my buddy saw a whale shark off to our port side that no one had spotted yet. The captain veered to port and dropped us in, giving us about ten minutes with this incredible animal all by ourselves before another boat showed up. I could not help but feel so small next to the huge animal out in the middle of the ocean.

Shark tourism debate

As someone passionate about the ocean and all the things in it, there is nothing I would rather be doing than swimming next to whale sharks. I truly believe these experiences, in which almost anyone can be up close and personal with animals like this, do a huge service to ocean conservation.

People only love what they know. Once someone has been exposed to something like this, it is hard not to care at least a little bit more about the ocean environment. Our boat that day, which was full, had no other scuba divers besides my buddy and me. This experience was opening up the ocean to so many people—non-divers—who might otherwise never get to see an animal like this in person.

But I am also torn because the experience seemed a bit like a circus. There were too many boats and too many people. One could not help but wonder about the safety of the whale sharks (and the humans). Were the current rules enough?

Pros and cons

These trips also bring in a huge amount of money to the local people, the marine park, and Mexico. What used to be a fishing boat (doing detrimental things to the marine ecosystem) can now make far more money taking eight snorkelers at US$150 each, without killing anything, and hopefully, the park fees go to improve protected areas of Mexico too.

I often find myself with questions like these after participating in ocean experiences around the world. Does the good outweigh the bad? I would rather give money to fishers for “not” fishing so that they can make a living and support their families without damaging the environment. Like it is often said, marine creatures are worth more alive than dead when you factor in what tourism dollars can bring in. But I also do not want the experiences we enjoy so much to cause harm to those animals we love.

At the end of the day, I think it is our responsibility to do the research and find out as much as we can about the ocean experiences we take part in. Are they being done the right way? Are they keeping the ocean (and people) safe?

Afterthoughts

I cannot deny that it was an amazing experience, and I would likely do it again if I was back in Mexico at the right time. But I do hope that the operators and the park service continue to make and enforce rules to protect everyone (and every living thing) involved.

I would suggest that there be limits on how many boats can be out there at one time. The number of whale sharks seen on our boat trip varied from day to day. I could see that on days with lots of whale sharks, boats would be more spread out. However, on our second day, the weather was bad, and it seemed that over 70 boats were crowded around one whale shark!

On a planet in which the environment and marine species are threatened in so many ways, whale sharks are no different. Their populations seem to be declining (although we do not necessarily have a good base on previous population estimates). We also do not fully understand where they live and spend time, where they mate and reproduce, or their migrations. They face threats, including shark finning, entanglement in fishing gear and pollution, ingestion of pollution such as plastics, being struck by boat propellers and ships, and changes in habitat due to climate change. They are listed as endangered on the IUCN list. I hoped we visiting swimmers were not on that list of dangers to whale sharks.

Encounters, like these around Isla Mujeres, can help whale shark conservation efforts by spreading awareness on a large scale. As long as the experiences are safe for the whale sharks, introducing more people to the wonders of the ocean can help increase knowledge and appreciation, sharing its wonders on a much broader scale.