Why sea shells vary in size across different regions

Why are sea shells from the tropics comparatively larger than those in the temperate regions? A new study may hold the answer.

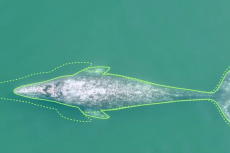

Seashells come in various shapes and sizes. And it appears that the seashells from the tropics tend to be larger than those found in the temperate regions.

Far from being just a coincidence, it seems that there is a rational explanation for it. Simply put, this is because the sea snails in the tropics have to devote relatively less energy to shell growth, compared to those in the cold-water regions.

This was the finding of a study recently published in the Science Advances journal and conducted by researchers from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (Coral CoE) at James Cook University. They discovered that sea snails and other calcifying marine molluscs devote less than 10 percent of their energy to shell growth.

Biomineralisation

To build up their shells, these animals extract raw materials from the seawater in a process called biomineralisation. One of the factors affecting this process is temperature, in that it is easier for the animal to extract the raw materials when the water temperature is warmer.

As a result, the sea snails and molluscs in cold-water regions like Antarctica have to use up more of their available energy to build their shells.

According to lead author Dr Sue-Ann Watson, “To keep costs down, we found that cold water molluscs opt to maintain a more modest and affordable living space.”

However, in the wake of ocean acidification and likely changes in seawater chemistry, brought about by rising carbon dioxide levels, the energy requirements of these animals may increase.

“This could challenge shell investment strategies and alter energy budget balances, with negative implications for other survival needs in calcifying animals, especially those with large shells or skeletons,” said Dr Watson.

The data set of the research spanned over 16,000 kilometres and included sampling locations like the Arctic waters off Svalbard, Norway to the tropical seas off Singapore.