The Mysterious Megamouth Shark

Of all known sharks, the megamouth is considered to be the rarest of all. The first one ever seen was a male, 4.5 metres long. It was dragged from the depths by a U.S. Navy ship off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii, on November 15th, 1976, having become entangled in their anchor line. It was so unusual that a new shark genus had to be created for it, and it was named Megachasma pelagios.

It was not until eight years later, in November, 1984, that another one was found, in a deep-sea net off California. It too, was a male 4.5 metres in length. The third, also male, was a metre longer, and washed up on the shore of Australia, on August 18, 1988. In the following years, megamouth sharks appeared more frequently in a variety of places around the globe.

The specimen found on a beach in Vietnam on June 02, 2015, (article here) was thought to be the sixty-eighth recorded find. But news of thirty-four more megamouth sharks has surfaced, all found around Taiwan during the past two years. They raise the total number found, to one hundred and two.

Alex Buttigieg, of Malta, better known as The Sharkman, has systematically collected all the information available about each specimen since the first one was reported. His records are now the most complete of all, and include photographs of every megamouth found, with the exception of the latest finds in Asia. They can be seen on his website, here.

“My interest in Megamouth sharks started the second that I found out about this very rare species.” he said. “Every record is interesting in its own right, but in some cases it is very difficult to collect the data. Most of the sharks are already dead when discovered and quite a few end up sold for food even before researchers can get to them. The best is when the shark is released alive . . . and possibly tagged as happened in the USA in 1990, and more recently this year in Taiwan.”

The megamouth is the smallest of the three filter-feeding species of sharks, with males maturing at about 4 metres and females at about 5 metres. The maximum confirmed length is over 7 metres. In comparison, the basking shark reaches a length of 8 meters, and the largest whale shark was measured at 12.65 metres.

Specialist Dr. José Castro, who has examined and dissected specimens of the elusive animal, writes : “We hardly know anything about this shark. Through tagging we know that it goes up and down in different depths, but tags cannot tell us the bigger picture of what the shark is doing and why.”

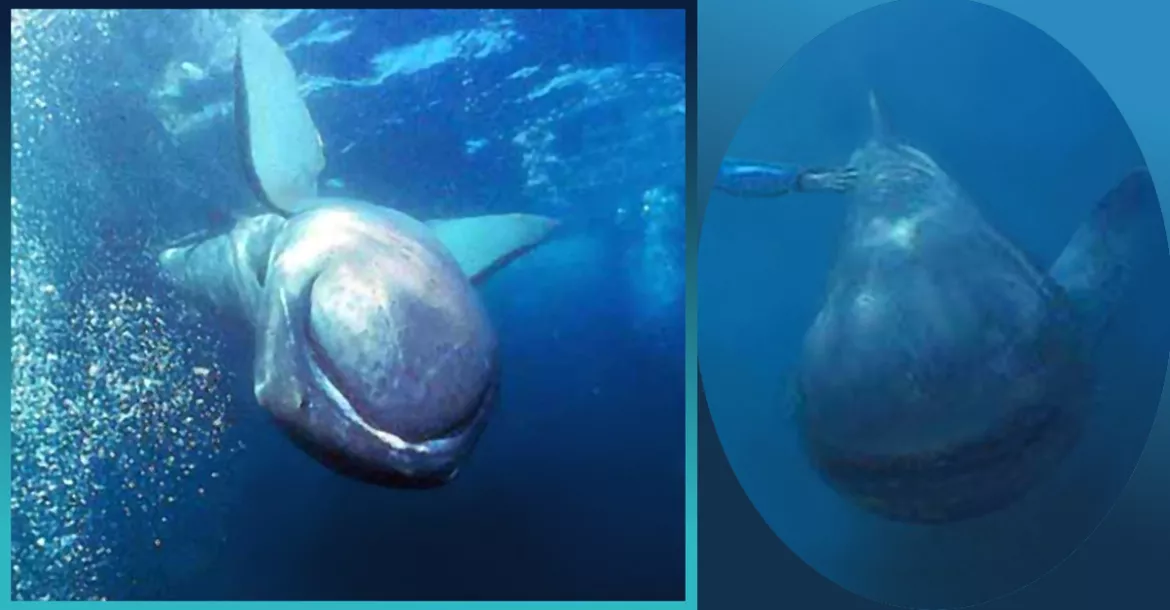

Like the other filter feeding sharks, the megamouth is wide-ranging, and has been found in tropical and subtropical regions of the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. It has a very wide head and mouth with tiny teeth, and a long tail. Its body is flabby; it has very loose, soft skin, connective tissues, and muscles, and its fins too, are soft. Castro believes that this indicates that the megamouth shark swims less strongly, and is less active, than the other filter feeders.

Another unusual megamouth feature is a white band on the upper surface of its snout that contrasts dramatically with its dark colour. This becomes more visible when its jaw is extended to eat, so it may serve the shark as it feeds. It may also help individual sharks to recognize each other. It has luminous photophores around its mouth, which likely serve to lure its prey closer, whereon it protrudes its jaws and sucks in the prey by expanding its mouth cavity. As it closes its mouth, the water is expelled through its gills.

Certain similarities between megamouth ovaries and those of mackerel sharks suggest to Castro that megamouth embryos are oophagous, meaning that the first embryo developed eats the other eggs in the uterus to gain the sustenance necessary to complete its development.

The male megamouth tagged off California was the sixth. It was a male, caught near the surface. According to Tom Haight, who photographed it, that warm summer of 1990 brought many unusual species to those coastal waters. The shark had become entangled in a drift net, and the fisherman, realizing that he had found something special, motored seven miles into Dana point, dragging the creature by the tail. Dr. Don Nelson, of California State University, was informed, and Haight accompanied him to see the shark.

He wrote : “As we approached, the shark seemed to welcome our attention, and showed no apparent signs of nervousness.”

The team spent four hours examining and photographing the animal, which was still tied with a rope around its tail. Finally, Nelson implanted a radio transmitter in it, and they released it.

The shark appeared unhurt by the ordeal, and swam slowly away, while the tag kept track of his depth. For the next few days, he swam at the slow speed of 1.5 km per hour. During the day, he remained at a depth of between 120 to 160 meters, and he ascended to between 12 and 25 metres at night, possibly following the krill that make up a large part of the megamouth diet. Krill also migrate between the depths in daytime, and the surface at night, a pattern known as vertical migration.

Nearly all megamouth sharks examined have borne scars from cookie cutter shark bites. The cookie cutter (Isistius brasiliensis) is a parasitic shark in the dogfish family, less than half a meter in length. Like the megamouth, it spends its days deep in the ocean, and rises to the surface at night. There it takes bites out of other sharks, fish, and whales by clamping onto them with lips adapted for suctioning, and then spinning to carve out a plug of flesh with its cookie-cutter teeth. It has the largest tooth-to-body size of any shark. Migrating vertically along with the cookie cutters, megamouth sharks would provide easy prey for them.

Alex says, “I believe that the main threats to megamouth sharks are the fishing nets. It could very well be that other megamouths are being caught elsewhere without being recorded. The recent records of 34 specimens discovered in Taiwan between April 2013 and May 2015 only came to light during the latest American Elasmobranch Society meeting presentation. This could also mean that these sharks are not as rare as they were once thought to be in some areas.

“Researchers are looking at the possibility that there could very well be breeding grounds off the coast of eastern Taiwan. The sizes recorded range from 2.5 metres to 7 metres. Hopefully the latest tagged specimen will be able to shed more information into this mystery. I also hope that action will be taken to protect these awesome sharks.”

About Alex Sharkman Buttigieg:

Alex became fascinated by the wonders of the submarine realm so accessible from the shores of his Mediterranean island at an early age, and was inspired to focus on sharks when Peter Gimble’s classic documentary “Blue Water, White Death” really brought them to life for him. He became a professional scuba diving instructor and spent his free time amassing all the information he could about every species of shark known.

Following in the footsteps of his life long shark conservation heroes (the late) Ron & Valerie Taylor and Rodney Fox, he started working towards shark protection and conservation, and was one of the first to warn of the dangers of overfishing them.

In 1997 he set up his web site “Sharkman’s World” dedicated to the education, conservation and protection of Sharks, and initialized and spearheaded the campaign for the Great White Shark protection in Malta, a campaign that lasted until September 1999, when the Maltese Government gave protection to the Great White shark and the Basking shark. There are now a total of 15 species protected in Malta.

Alex has dived with and studied sharks in many parts of the world including The Red Sea, South Africa, Fiji and Malta. He takes an active part in many international campaigns for shark protection. In 2007, he set up The Shark Group, an internet based forum and also in the same year, Sharkman’s World became a member of the international Shark Alliance. In 2008, he was the co-founder of the Let Sharks Live network, and with The Shark Group, initiated the International Year of the Shark in 2009.

He has attended and spoken in many International conferences for shark conservation, is a regional investigator for the Mediterranean Sea, and works with the Global Shark Attack File (Shark Research Institute, USA). He also collaborates with: Shark Research Committee (USA), the Australian Shark Attack File, and Fishbase.

Alex has written various articles and contributed data and information for T.V. documentaries, scientific publications and books.

(c) Ila France Porcher

author of The Shark Sessions

To subscribe to my newsletter, click here

- Log in to post comments