Since 2017, a team of divers from Global Underwater Explorers (GUE), along with Soprintendenza del Mare (Superintendent of the Sea) and the RPM Nautical Foundation, has been involved in archaeological investigations at the site of the Battle of the Egadi Islands in Southern Italy.

Contributed by

The Battle of the Egadi Islands (also known as the Battle of the Aegates) was fought between the ancient Roman and Carthaginian naval fleets on March 10 in 241 B.C. The battle between the two fleets involved more than 500 ships and ended with a decisive victory for the Romans. It was also the last battle of the First Punic War, which had lasted 23 years.

During the past five years, the GUE Egadi Project dive team has completed 32 missions. During this time, they have made 101 team dives and 263 individual dives, which is equivalent to about 10 days of bottom time and about 38 days of decompression time. That’s a lot of time underwater!

I recently had a chat with Mario Arena, one of the project leaders alongside Chicco Spaggiari, about their ongoing underwater efforts to recover a key part of human history.

AW: How did you both get involved in the Battle of the Egadi Islands research?

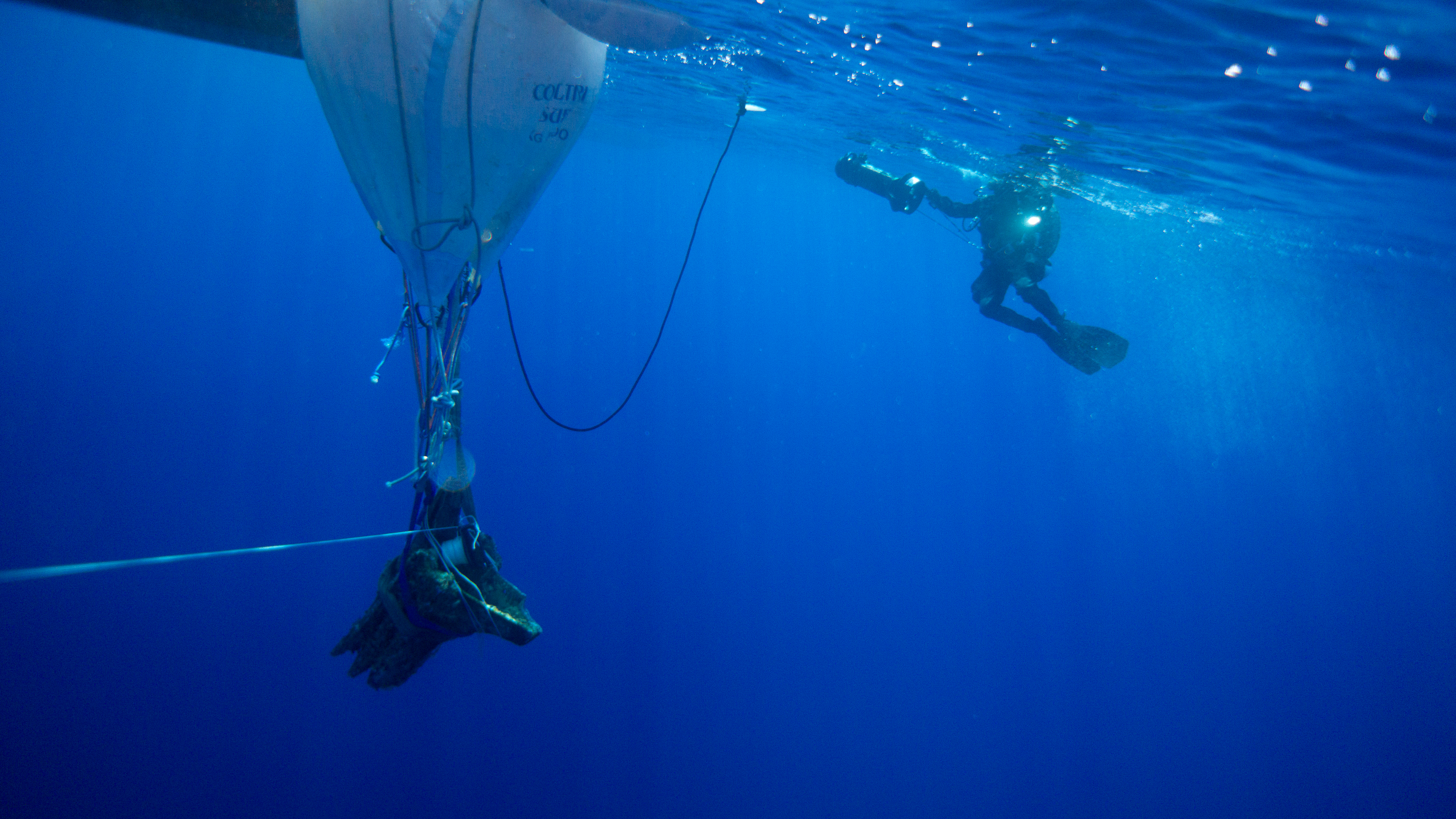

MA: Chicco and I have collaborated with the Sicilian archaeological authorities (Soprintendenza del Mare/SOPMARE) for twenty years, and we have participated in several significant projects together. We knew about the impressive discoveries at the site of the Battle of the Egadi Islands, and it was a dream come true for us to contribute to this research. The opportunity began when a specific artifact, a bronze warship ram, needed to be lifted. It was mostly buried and challenging for RPM’s ROV (remotely operated vehicle) to dig out. Chicco was maintaining subtle but constant pressure on the archaeologists to involve us in the Egadi battlefield, so when the day came that they finally asked, we were happily on board.

AW: Why is the Battle of the Egadi Islands such an important moment in history?

MA: The archaeological site is of incredible importance since it is the only ancient (over 2,000 years old) battlefield, terrestrial or naval, that has been discovered to date. It offers a unique opportunity to learn about the military culture of the time. The battlefield also represents an important moment in Roman history, since Rome—which at that time was still an emerging power—prevailed in a 23-year-long war against the Carthaginian Empire, the predominant power at the time. Even more importantly, it signaled Rome’s complete dominion over the sea. This was the event that enabled Rome to build the incredible empire we all know. It is also the first time that historical sources narrating huge and significant battles can be confirmed with sound archaeological evidence.

AW: How has RPM’s work benefited from having a team of highly skilled divers to assist them?

MA: Let me first say that RPM’s underwater archaeology operation is incredibly efficient. They use state-of-the-art technology, they work with some of the best marine archaeologists in the world, and they had the stubbornness to keep searching the area for years before finally discovering the battlefield site. Italy and the whole field of archaeology owe them immense gratitude for what they did and for what they are still doing on this site.

Our GUE divers’ contributions help the operation in several ways: First, we can offer a better eye for discovering artifacts in areas where the electronics lose most of their efficiency, like in rocky areas and under the sediments. In these conditions, the artifacts are hidden to the long-range “eyes” of electronics, which means they cannot be targeted for investigation with the ROV.

AW: How do the divers find things? It sounds like a lot of scootering.

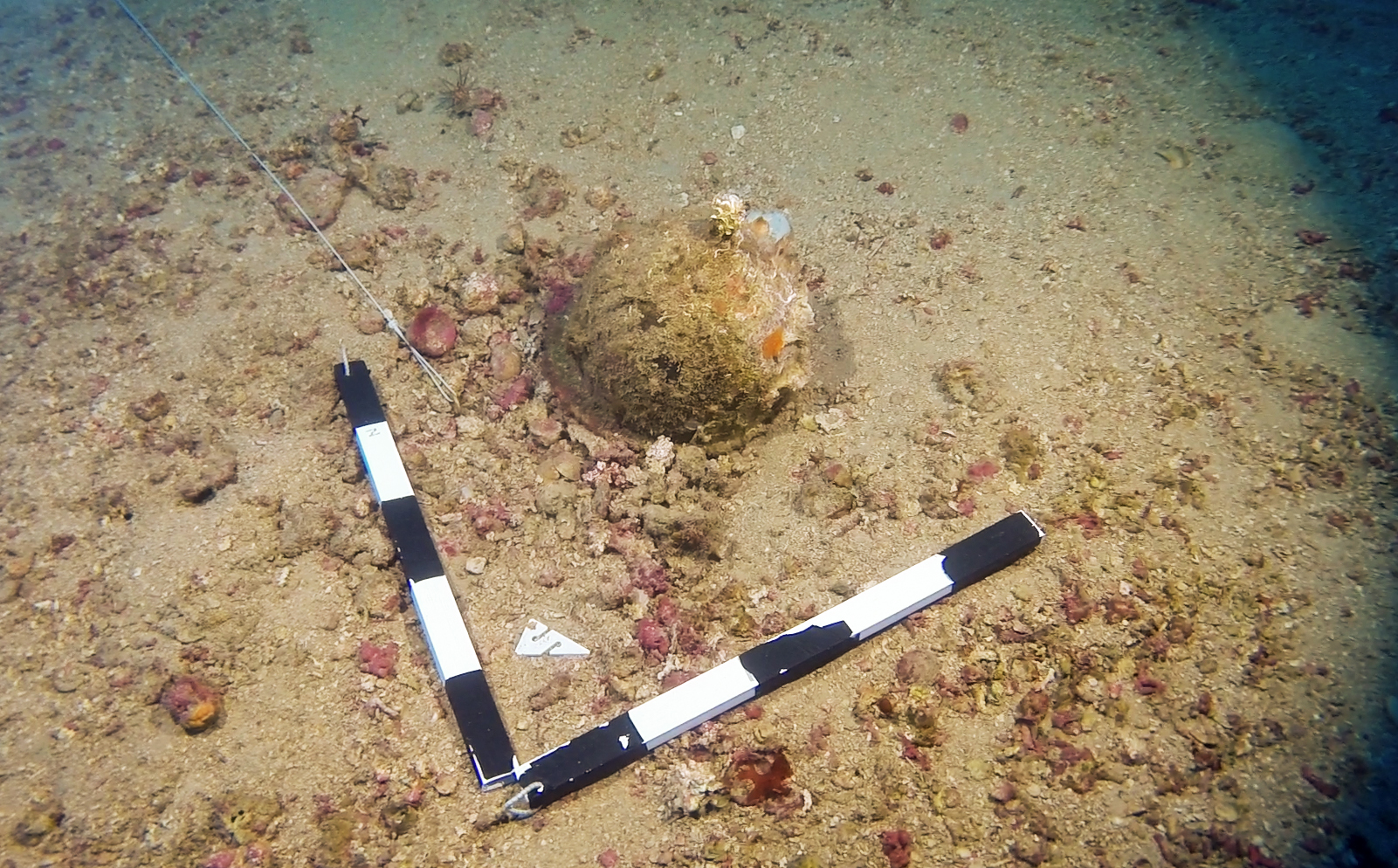

MA: The teams of divers systematically explore the seafloor, visually or with metal detectors. Divers are more efficient, quicker and more delicate than the robotic arms and tools of the ROVs in uncovering artifacts that are partially or completely buried and preparing them to be lifted to the surface.

We are also more efficient in setting up grids and sectors, performing photogrammetry—artistic pictures and videos offering quality documentation of the artifacts on-site—and managing the operations. These are all important contributions to the archaeologists’ investigations.

AW: How have metal detectors changed the way your dive team works underwater?

MA: They shifted a lot of our attention to what is below the sediment, opening a new frontier for the investigation of this site. We rely on metal detectors mostly for smaller items, like helmets, swords, parts of armor, coins, nails and other less visible artifacts. It is true that bigger artifacts, like warship rams or anchors, could be found completely buried. But you never know, since a few rams were found buried up to 80 or 90 percent of their volume. It is very thrilling.

AW: Was there a lot of trial and error involved in finding the best way to search for possible artifacts?

MA: Let’s say that we had to invent and test a lot. The nature of this site is very different from a simple wreck. Here, we were working on an area that measures at least 4km (2.48mi) by 3km (1.86mi), and the battle’s debris is spread throughout this area with no logical order. Such a site would present archaeological challenges on dry land, and it was even more difficult in the middle of the sea at a depth of 80m (263ft).

AW: Can you describe the process of artifact recovery?

MA: It varies according to different artifacts and depending on the conditions in which they are found. Generally speaking, it is very important to record the artifacts’ positions and to document their status when found before moving or removing them. It is also important to have a stabilization and preservation plan ready before recovering an artifact.

AW: I understand that you used a dredging tool called the SUEX-Rosa. Can you explain how it works and how it helped with the archeological recoveries?

MA: It is a great tool that allows us to vacuum the sediment of the sea bottom away from an artifact. The concept was invented by a project team member, Cristiano Rosa, and then refined and developed by SUEX, an Italian company and leader in manufacturing underwater propulsion vehicles. Its working principle is based on the use of a DPV and the suction that the propeller creates on the front side, opposite the propulsion side. This suction is conveyed through flexible piping used for vacuuming the sediments. It is pretty effective, and an incredible feature is that it is self-contained and can be carried by divers. Normally a dredge would require a pontoon, with a four-point mooring or a dynamic positioning system, and dozens of meters of piping connecting to the surface. Cristiano invented a brilliant tool.

AW: What were the feeling and mood when that well-preserved and finely decorated helmet was found last year?

MA: These kinds of finds are incredible and unexpected. The most exciting thing is that you really do not know what else will be discovered at that site. I think that we still have plenty of impressive artifacts to find.

AW: How has the environment of the battle location impacted the project?

MA: Well, it is a very challenging environment. Besides the depth, it is in the middle of the sea in an area where strong currents are always present. We keep trying to refine procedures, but the very high skill level of the divers involved is integral to getting the job done.

AW: Has photogrammetry helped with studying the artifacts?

MA: Photogrammetry is an important tool for the archaeologists, as it enables them to see the artifacts from any perspective and to measure dimensions and distances. It is much more than a simple picture; it is a scaled 3D model of the object.

AW: Where do the recovered artifacts go? Are they being studied or are they publicly displayed?

MA: Both. They undergo a process of stabilization and restoration first, and then are (or will be) analyzed and studied by scholars and specialists in different disciplines. The final destination is the Museum of the Tonnara of Favignana, which is a spectacular facility that we hope will someday include the Museum of the Battle of the Egadi. The most magnificent artifacts, like the warship rams and the best-preserved helmets, for example, are often on tour, being displayed in dedicated exhibitions in museums all around the world.

AW: Can you describe what a typical day on the project is like from start to finish?

MA: It is a demanding routine. We normally meet around 7:30 a.m., after breakfast, to refine a plan for the day and complete preparations. We load the boat at 8:30 and try to leave the dock between 9:00 and 9:30. We are on-site by 10:30, and divers hit the water around 11:00. Dives last for four to five hours, so we are out between 3:00 and 4:00 p.m. and are back in the harbor and unloaded between 4:00 and 5:00 p.m.

At that point, we still have to fill tanks, conduct rebreather checks, charge batteries, unload and organize the team reports, discuss the results and plan for the next day. Then we eat, sleep (hopefully by 10:00 p.m.) and then repeat.

Ideally, we would like to do three days on and one off, but we typically go anytime the weather allows. Last year, we did two days of diving and one day off, seven days of diving and three days off, and then five days of diving. I have lost 5kg (11 lb) of weight as a result!

AW: What was one of your favorite moments in the past few years of this project?

MA: I love when we sail out to the site at high speed with the team. It feels as if I am going to battle. Also, the days when we recover rams to the surface are special.

AW: How can divers get involved with the project? What are you looking for in team members?

MA: Chicco put it nicely this year saying, “We want you all, but planning to participate in this project is like planning to run the New York City marathon. You have to prepare for it, seriously, and train for it the whole year. For working on the bottom, we seek GUE rebreather divers with solid experience diving at sea.”

Standardization of equipment and procedures are important in such a complex and challenging operation. We prioritize photographers and videographers, people with expertise in photogrammetry, survey methods, fixing equipment, and those kinds of engineer-type skills. Medical backgrounds are also a plus, as well as a boat license.

We would also like to have more safety divers, and for this role, we require a GUE Tech 1 or 2 certification or new GUE rebreather divers.

AW: How has the pandemic impacted the Egadi project?

MA: Of course, it impacted the project, but we have been very happy to be able to make it run, even if we had a reduced team. Chicco and I just kept our heads down and stayed motivated to try to make it happen. All the team members from outside Italy were not able to join, and we had a total of six divers during the three weeks of operation in 2020. Nonetheless, it has been a very successful campaign.

AW: What are your future plans for the project? What remains to be done?

MA: We hope to keep being involved in the investigation of this site for many years to come, and we have already organized a 2021 campaign. I think we have only scratched the surface on this site, and that discoveries will keep surprising us for years to come. There is still a lot to learn. ■

For more information, please contact Mario Arena at mario@gue.com or Chicco Spaggiari at chiccospaggiari@gmail.com. Learn more and follow along with the developing discoveries at: facebook.com/BattleofEgadi.