Microplastics and the Ocean: The Invisible Threat Divers Can Help Monitor

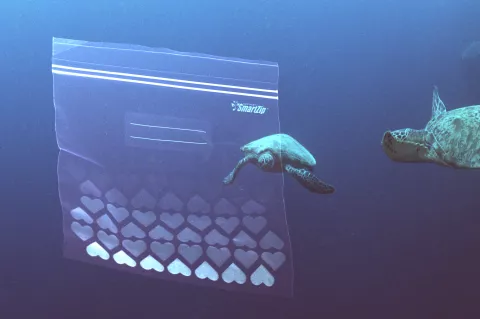

Distressing images of turtles with plastic straws sticking out of their bodies or dead seabirds with stomachs brimming with synthetic trash justifiably attract public attention.

However, this pollution extends to the microscopic scale from an increasing number of micro and nano plastics. These tiny particles permeate the depths of the oceans, posing significant health risks to marine creatures and humans alike.