Scuba instructors and divemasters may be heroic, caring people but they don’t always make perfect role models!

Contributed by

Factfile

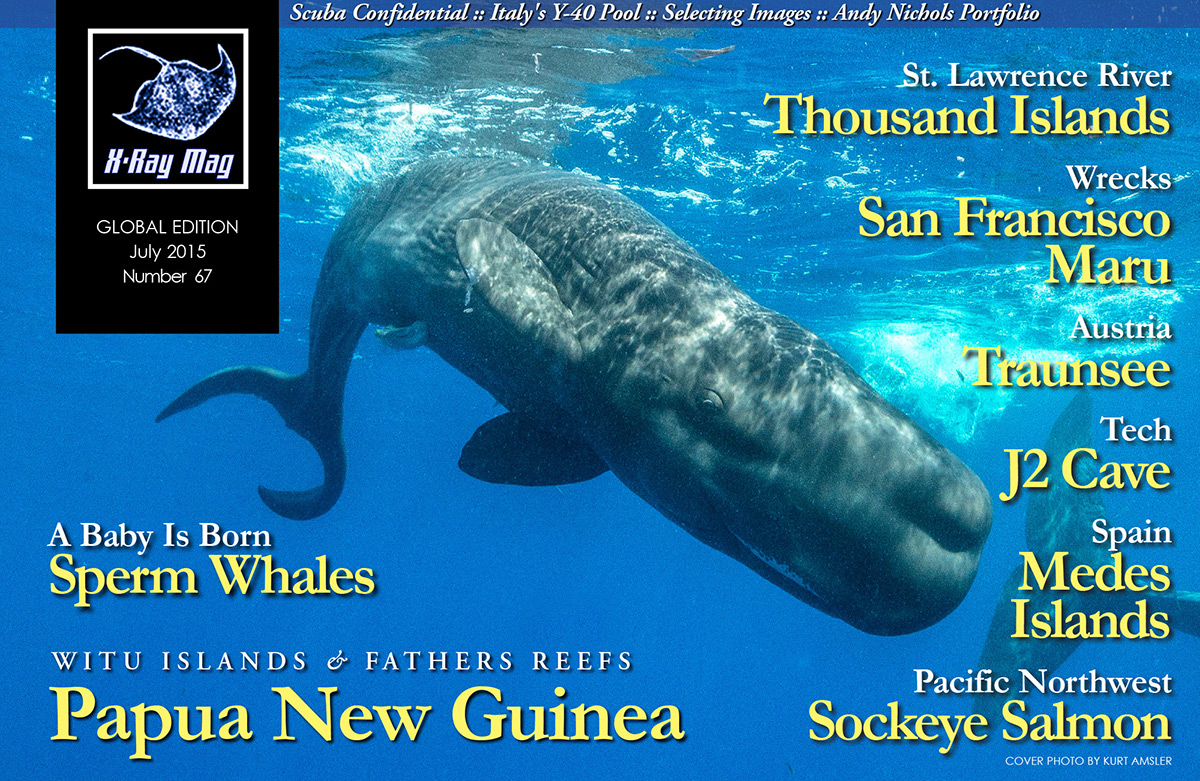

Simon Pridmore has been part of the scuba diving scene in Asia, Europe and the United States (well, Guam) for the past 20 years or so.

His latest book, Scuba Confidential, is available in paperback, audiobook and e-book on Amazon.

His forthcoming book, Scuba Professional, was released in June

Your first dive instructor is a golden god of the sea! He or she has the answers to all the questions, sees everything that goes on, is always around to offer help when you need it, and, most impressive of all, can move around underwater effortlessly like a fish while you flail around awkwardly. Nothing is ever a problem; life is fun and full of high fives.

As you gain more experience, you realise that the tanned, blond deities that greet you when you arrive at dive resorts may have only been there a few weeks and could have fewer dives logged than you do.

This is of course all part of the scuba diving industry. We sell a certain relaxed, carefree lifestyle. Advertising for scuba instructor training entices candidates with images of gorgeous coral reefs (your future office), cool dudes and chicks in sunglasses (your future colleagues) with the wind blowing in their hair as their speedboat carries them off to the next dive site (conference room.)

The reality, of course, is very different. After the customers have returned to their hotels, the real work begins: filling cylinders, washing and fixing equipment, doing the paperwork, preparing for the next day’s classes and dives, nursing aches and pains and reviewing the day’s work to see where mistakes were made or what could have been improved. Believe it or not, it is work!

We do not tend to show the work that goes into preparing for a dive because that is not what the customers want to see. The perfect dive operation can be compared to a duck, serene and effortless on the surface, with lots of unseen paddling going on beneath. This misleads many into believing that when you become expert you do not have to prepare so assiduously or take so many precautions. The truth, as professionals often learn by bitter experience, is that the more familiar you are with a procedure, the more instinctive it becomes but the more careful you have to be to guard against complacency and carelessness.

Preaching and practising

You will see many examples where professionals say one thing and then appear to do exactly the opposite. For instance, an instructor will tell his beginner students about the inherent risk in diving a yo-yo profile with frequent ascents and descents; and then on dive four of their course, he will escort all six of them individually as they practice emergency out-of-air ascents to the surface from 6m (20ft) to the surface, going up and down several times, (yes, like a yo-yo) in that part of the water column where the pressure change, and therefore the risk, is greatest.

Similarly, no diving manual would ever condone the practice of doing a deep bounce dive incorporating substantial physical stress followed a few minutes later by a longer dive to the same depth, but this is something that divemasters in some areas do, several times a day, as they set the shot line into a wreck and then ascend in order to pick up the group and guide them around the site.

The fact that contradictions exist between what we preach and what we practice does not mean that our advice is flawed and that the practices are safe. Nor does it imply that we are indeed mythological “dive gods” and that somehow the laws of physics and physiology do not apply to us.

It is true that, when they dive 20 to 30 times a week, every week, professionals develop a high level of dive fitness. They are also aware of the risks involved in some of the work they are required to do and mitigate the risks wherever possible, for instance, by ensuring their equipment is in perfect shape and keeping themselves well rested and hydrated.

However, it is also the case that the risks sometimes carry painful rewards and, unfortunately, although this is certainly not something that the scuba diving industry advertises widely, professionals are more frequent visitors to the recompression chambers than their amateur counterparts. Most long-term dive instructors have aches and pains accumulated over years of submitting their bodies to constant pressure changes.

The paradise conundrum

A beach on a remote tropical island may seem like paradise when you visit for a couple of weeks but limited entertainment opportunities, overconfidence and maybe the fact that they have swallowed some of the “dive god” propaganda themselves can induce those who have to live and work in paradise to do some pretty dumb things. Don’t try any of these things at home, or anywhere else for that matter!

5 dumb things dive pros do

1. Put their scuba gear on by placing it in front of them, tucking their arms through the shoulder straps and throwing it over their head, and possibly straight onto the head of anyone walking or sitting behind them at the time.

2. Make a forward roll entry from the deck or dock in full scuba gear to show how superior they are to the mere mortals with their giant strides and back rolls.

3. Make an ultra deep single tank bounce dive on air on their day off when there are no students or customers around and when, therefore, they imagine the universal rules of physics have been temporarily suspended.

4. Strap on a used cylinder at the end of the day to “use up the air” or to “pop” down and free the boat anchor, instead of using one of the perfectly good full cylinders available.

5. Stroke or feed marine animals with teeth, spines or stinging cells. Whether the pros do this out of boredom or out of a misguided desire to entertain their customers, this behaviour is not good for the animal. Neither is it good for other divers who subsequently pass by and may be attacked by the animal, which has come to associate divers with harassment and/or food. ■