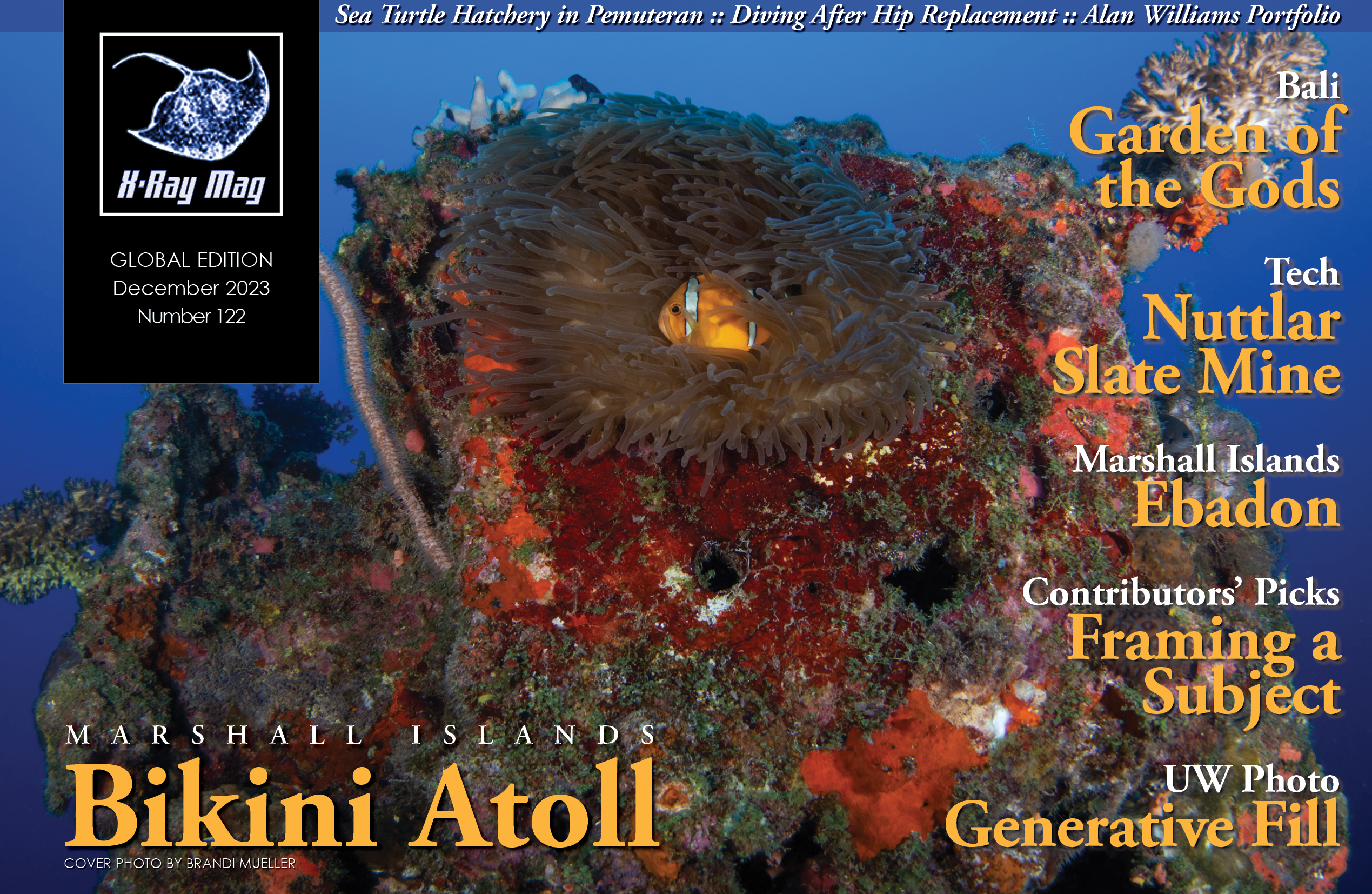

A far-flung location in the Pacific, which can only be reached via liveaboard, Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands is the site of a fleet of WWII wrecks. Sunk during post-war nuclear testing, the wrecks are now encrusted with marine life. Brandi Mueller shares her adventure there.

Contributed by

Bikini Atoll is arguably one of the most remote and adventurous dive locations left on Earth. It is literally in the middle of the Pacific Ocean; depths here allow only trained technical divers to reach the wrecks and the atoll feels (and has been) abandoned and deserted in every way. But Master Liveaboards has returned to the location, post-Covid, to bring divers to the wrecks in luxury and comfort—even with internet connection to the outside world via Starlink. I cannot think of a better way to dive this bucket-list location.

Just a tiny green speck within the expanse of the Pacific Ocean—but with a unique history, unlike any other—the islands of Bikini Atoll make up barely two square miles (5 sq km) of land, which encircle a lagoon that is 25 by 15 miles wide (40 by 24km). Averaging only seven feet (2.1m) above sea level, the islands are small, but their history is huge. Chosen for its remoteness, this atoll (which few can point out on a map) will forever be part of history, as the location for the first public testing of nuclear weapons.

The lagoon now holds a technical diver’s dream for wreck diving. With a seafloor depth of 165ft (50m), fourteen ships and submarines, which played important roles in WWII, rest peacefully under the vibrant, warm blue waters; but the war did not send them there, Operation Crossroads did.

Following the American nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which led to the end of WWII, it was decided that tests should be carried out to see just what this new technology could do. A target of 95 ships was set, which included four US battleships, two aircraft carriers, two cruisers, eleven destroyers, eight submarines, numerous amphibious and auxiliary vessels, plus three surrendered German and Japanese warships.

The goal was to investigate the effects of nuclear weapons on warships. To do this, the ships were set up as if actively on duty and fully loaded. Fuel was left in the tanks, bombs and other weapons were within the holds and on decks, and airplanes were staged on the aircraft carrier. All this was done to see the aftermath effect that a nuclear bomb might have on a ship at sea. The damage, as a function of distance from the blast center, would also be measured. The results of that testing have left an underwater shipwreck playground for divers who are willing to make the voyage.

The journey

Master Liveaboards started making Bikini accessible to divers in 2018, but it was just for two seasons as... well, we all know what happened in 2020 (ed. – the coronavirus pandemic hit, and operations had to cease). After almost three years of being closed, the Marshall Islands was one of the last countries to open post-Covid.

Getting to isolated Bikini Atoll is not easy, and the 250-mile (360km) journey from Kwajalein Atoll to Bikini Atoll is best done in the summer months, when conditions are more likely to be calmer. Master Liveaboards resumed its trips to this far-flung destination in the spring of 2023, sending two of its boats, the Pacific Masterand the Truk Master—likely catching up with all those passengers who have been waiting, since before Covid times, to go on the dive trip of their dreams. I was one of those passengers who was scheduled to go on what would be my second trip to Bikini Atoll, back in the summer of 2020—a time that seems so long ago, it might have been a different era.

The long journey to Bikini Atoll—or what I lovingly refer to as “the middle of the middle of nowhere”— started for me in Chicago. My route included flying to Denver, then Honolulu, spending a night in Honolulu, and then setting out the next morning on United’s “Island Hopper” flight, which runs from Honolulu to Guam twice a week, stopping at five Marshall and Micronesian islands on the way.

My flight out of Denver had maintenance issues, and as the hours ticked on, I started getting worried that I might not even make it to Honolulu in time for my flight to Kwajalein, which only occurred twice a week. In the end, the flight was eight hours delayed, and I arrived in Honolulu around 3 a.m., with my next flight departing at 7 a.m.

Thankfully, there was plenty of time to make the flight, but no time to get the sleep and shower I had hoped for at a Honolulu hotel I had booked. But I was happy not to miss the flight, and I tried to keep my eyes open as I stayed awake all night for that morning flight.

On to Kwajalein

Departing soon after the sun came up, we left Honolulu and headed west. The flight stopped at Majuro and continued on to Kwajalein, where we disembarked. Kwajalein Island is part of the US Army Garrison Kwajalein Atoll, a secure military base. With papers in hand explaining our reason for getting off the plane, we were led to a holding area where Army personnel looked at our passports and papers, and stamped us through. We collected our luggage and were bussed to a ferry pier where Craig Johnson, a captain from Master Liveaboards, was waiting for us.

The unthinkable happened and a few passengers did not receive their luggage, which made me cringe for them. Would they be able to get it back at all? Usually, the boat headed straight for Bikini (a 30-hour journey from Kwajalein), and the next day’s flight would be coming from Guam, not from Honolulu, where presumably the bags had been left. They chatted with Craig, and he started to form a plan.

The ferry boat arrived, and we got underway for a 20-minute ride to Ebeye Island, where most of the local Marshallese, who worked on the Army base, lived with their families. Once on Ebeye, the crew of the Pacific Master met us with a flatbed truck to load our luggage and transport it to the liveaboard, which was waiting for us at another pier.

The liveaboard

We boarded the 100ft (30m) Pacific Master and were shown to our rooms. Accommodating up to 20 passengers in 12 staterooms, the spacious boat had lots of room for dive gear, camera gear, lounging outside or inside in the salon. One of my favorite things about this boat was that it had four single cabins for those traveling solo. Several cabins had en-suite bathrooms, while other cabins shared bathroom facilities on the main deck.

After seeing our rooms, we moved to the salon for a safety briefing and a few drills, including life-jacket donning. The liability waiver to dive Bikini Atoll was like none other. You must place your initials next to the box that read, “I understand that the United States government conducted 23 atomic and hydrogen bomb experiences at Bikini Atoll between 1946 and 1958, and that the ships I will dive on at Bikini received radiation from some of the tests,” among others.

We set up our dive gear, and I started setting up my camera inside the salon. There was a large charging area for batteries and dry space for camera setup and storage.

Dinner followed, and soon after, most of us were ready for bed. I felt like I had not slept in days.

Normally, the boat would have left for Bikini that evening, but because of the lost luggage, we would be staying at Kwajalein until the next morning and dive the Prinz Eugen. This ship was part of the Bikini nuclear testing and initially survived the tests but ended up sinking after being towed back to Kwajalein for research.

I thought it was an exceptional decision, to rearrange the schedule to accommodate the passengers whose luggage was delayed. We all crossed our fingers and our toes for them, in hopes that the luggage would arrive the next day.

Prinz Eugen

History. The Prinz Eugen was commissioned into the Imperial German Navy in 1940. Named after the 18th-century Austrian general, Prince Eugene of Savoy, the 681ft (207m) Admiral Hipper-class heavy cruiser carried a crew of 1,382 men. Alongside the Bismark, the Eugen was part of Operation Rheinübung in 1941, which attempted to block shipping between England and the Allied Forces. At the end of World War II, the Prinz Eugen was surrendered to the British Royal Navy and transferred to the US Navy as a war prize.

After WWII, the ship then made its way across the Atlantic to the United States, through the Panama Canal into the Pacific Ocean, and finally arrived halfway around the world at Bikini Atoll, to be used in the nuclear testing. The ship survived the Able and Baker bombs, but because it was highly contaminated, the Prinz Eugen was towed back to Kwajalein Atoll to be further studied.

Several months later, in Kwajalein, a small leak in the hull was discovered, but the ship was still too radioactive to allow for repairs. In the process of towing the ship out of the lagoon to be skuttled in open ocean, the ship struck Enubuj Island and capsized upside down.

Diving. Jumping off the back of the Pacific Master, we followed a marker buoy that led down to the bow of the ship. The Eugen rested on a slope, with the bow at the deepest point, and the stern broke the surface, with parts of two propellors and the rudder reaching out of the water. (The third propeller was given to the German Naval Museum at Laboe.) Just seeing the space between the above-water propeller blades and the buoy marking the bow gave one a seemingly unreal view of how large this ship was. It seemed a huge distance between the bow and stern, and it was.

Reaching the sand in front of the ship (around 120ft / 36m), I looked up, and once again, was stunned at the immensity of the ship. The bow seemed to rise up in front of me like a skyscraper. It was possible to swim under the bow, and also penetrate into the bow. I followed one of the dive guides in, and because the ship was upside down, light bulbs could be seen under us in a perfect row. There were bathrooms with sinks and toilets. I went back out of the hatch under the bow and swam alongside the ship.

Much had toppled over into the sand, but plenty could still be seen. Peeking into an open porthole, I could see interior rooms with chairs upside down. A torpedo room was easily seen, with at least six stacked torpedoes. Back towards the stern, in shallower waters, an 8-inch deck run lay in the sand. I rounded the stern and glimpsed the propellers, surrounded by a massive school of glittering bait fish. Continuing along the hull, I was amazed by the amount of fish life and coral growing on the wreck.

That afternoon, in what I considered a small miracle, the lost luggage arrived, and the crew from Master Liveaboards headed over to Kwajalein to retrieve it. We had all had an excellent time diving the Eugen, and as dinner ended, the liveaboard headed north and west for Bikini Atoll.

Operation Crossroads

In 1946, three Fat Man plutonium implosion-type nuclear weapons were scheduled to be tested in the lagoon of Bikini Atoll. For the first time, media was invited to go halfway around the world and watch these tests—another sign that showed how the United States wanted the world to know how destructive these weapons were. The testing was conducted by the Joint Army/Navy Task Force One.

Not everyone was supportive of this endeavor. Scientists protested that they already knew the effects nuclear weapons had on humans and animals (it was bad). Diplomats protested that this show of power might not lead to adversaries backing down, but instead cause them to ramp up their weapons production and development.

Animal rights activists also joined in the protests, because the National Cancer Institute wanted to do tests on animals, including pigs, guinea pigs, goats, rats, mice and even grains containing insects. Not to mention, some protested that over US$450 million dollars’ worth of target ships would likely be destroyed (although, counterprotests pointed out that most of these ships were old, and their value was a lot less as scrap metal).

One of the reasons for selecting Bikini was that it was “mostly” uninhabited. But “mostly” meant that 167 people still lived there. Prior to the nuclear tests, they were asked to leave their island “for the good of mankind and to end all world wars.” They were moved to Rongerik Atoll, an island close by. When the Navy commodore in charge came to ask the people to leave, he also brought a film crew, and several retakes were staged to show the Bikinians agreeing to this eviction. They had been told they could return home shortly after the testing, but this turned out to be very untrue, as the island is still uninhabitable to this day.

The first bomb, Test Able, was dropped on 1 July 1946 from a B-29 Superfortress. It was detonated at 520ft (158m) above the target fleet and was similar to the Hiroshima bomb drop. Able missed its target by 2,130ft (650m); it has never been determined why. USS Nevada was intended to be its main target (and it was even painted orange and white so it would stand out); but instead, Able hit closer to USS Gilliam. In the end, five ships were sunk: USS Gilliam, USS Carlisle, USS Anderson, USS Lamson and the first foreign vessel, IJNSakawa. There was almost disappointment about the lack of media-worthy hype that the first bomb created.

The second bomb, Test Baker, was planned to be detonated on 25 July 1946, at 90ft (27m) below the ocean surface, under USS LSM-60. The LSM-60 was presumed to be vaporized, and no part of it has ever been identified. The underwater detonation led to very unique circumstances; the underwater fireball became an expanding hot gas bubble that hit the sea floor and the surface at the same time. The force underwater damaged the hulls of ships from below, and when the gas bubble hit the surface, it sent two million tons of spray and seabed sand into the air, in the form of a 6,000ft (1,828m) tall, hollow column with 300ft (91m) thick walls.

Underwater, the gas bubble hit the seafloor and created a crater that caused a tsunami, which made a wave that lifted ships as high as 94ft (28m). Then, the waterfall of spray came down and washed the entire test fleet in radioactivity.

The press and media had wanted something to write home about, and they got it. Ten ships were sunk, including the LSM-60, USS Arkansas, USS Pilotfish, USS Saratoga, YO-160, HIJMS Nagato, USS Skipjack (which was later raised for research), USS Apogon and ARDC-13 mobile dry dock. The Prinz Eugen was also considered sunk by Baker, even though it did so five months later. Plus, the entire target field was washed in radiation. The third test, Charlie, was cancelled.

The wrecks of Bikini

USS Saratoga. Arriving in the middle of the night, we woke up to a fiery-orange sunrise, ready to dive the Saratoga. A darling of the US Navy, the “Sara” was one of the world’s first aircraft carriers. The 39,000-ton Lexington-class aircraft carrier is 888ft (270m) long with a 105ft (32m) beam and had been decked out for the tests.

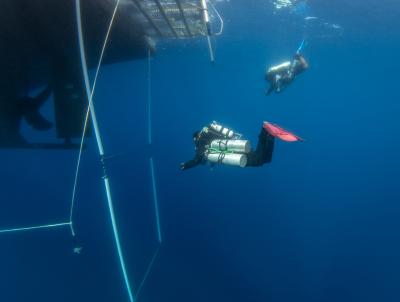

During preparations before the dive, the Pacific Master’s crew members were fantastic. They carried stage tanks and cameras to the dive deck. They helped us clip on tanks and passed gear into the water. One could get used to such service.

I jumped off the platform and started to make my way down to the Sara. Visibility was not ideal, probably due to a big storm a few weeks before. I was the first person in the water, and while descending down the mooring line, I noticed something gray out of the corner of my eye. Then, it swam right in front of me—a curious reef shark. I looked around and saw I had an entourage of sharks following me to the ship.

There is just something about the size of an aircraft carrier underwater that is almost unfathomable. As I got closer, the shadow of the ship in the blue waters grew until it was all that was below me—just a massive ship.

We were tied up close to the bow, and I swam out in front of the ship to take in how big it was. Instead of a point, like one is used to seeing when looking at a ship from the front, the Sara’s bow looked like a long line—plenty of space for planes to take off and land.

Parts of the flight deck had collapsed, opening up areas to the floor underneath. I ventured in and saw gauges, panels, toilets and sinks; and at one point, I looked up from under the flight deck and saw the underside of a sea turtle. I went back out onto the top deck and saw a sea turtle munching happily on sponges growing on the ship.

Moving back towards the flag bridge, I noticed a distinct scientific instrument on the deck. A blast gauge tower (these types of towers were nicknamed “Christmas Trees”) held up a circular object, which was made to measure blast strength. In-between the tower’s two large brass plates, there would have been tin foil, and the plates matched up with differently sized circles. If the smaller circles ruptured after a blast, it was deemed a large blast; if only the bigger circles ruptured, the blast was considered a smaller one.

The flag bridge on the wreck still stood and was an easy swim-through. The helm, compass and other navigational equipment were still intact. The porthole covers on the windows were battle-ready, so minimal light could be seen outside the ship. Other porthole covers rested on the floor. With limited bottom time, I made my way back to the Pacific Master to do my deco stop near its hang bars, off the back of the boat.

We did several dives on the Sara throughout the week and visited interior spaces, including the machine shop, galley, crew quarters and dive locker, and some divers even went to the famous dentist room. Closer to midship, a plane could still be seen, although it was a bit mangled. Recently, dive guides found the pilot’s ditch bag by the plane and opened it up to find collapsible paddles, a canvas object that may have been an inflatable raft of some sort, and other things a pilot might need, should he end up in the water. Three airplanes were blown off the deck during the blast, and two could be seen off the starboard bow at 165ft (50m).

While underwater wrecks are always in a constant state of decay, there is still plenty to see, and sometimes, when things break up, they reveal new areas to explore and new things to see. One of my favorite things to do on this trip was sitting around in the salon with the other divers, looking over ship plans, and doing research on the internet, trying to find more information that would help us plan our dives. The ship’s plans of the Saratogawere always laid out, and we traced our fingers over the places that we had been and contemplated how to get into other spots. It seemed like there were not many places left on the wreck that we could explore and perhaps see something no one else had seen in over 75 years.

HIJMS Nagato. HIJMS Nagato is probably the next most notable ship in Bikini Atoll. The Nagato was the flagship of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet. This ship sat upside down, with four massive propellors standing out as the first thing we saw upon decent. It was the only Japanese battleship to survive the Pacific War and was taken over by the United States after its surrender on 30 August 1945. This was the ship from which Yamamoto radioed in the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

When it was launched in 1919, it was the largest and fastest battleship in the world and the first to have 16-inch guns (several of which we swam around). Its mast was modified in the 1930s to a pagoda mast, which rose up 135ft (42m) from the ship. Underwater and upside down, that pagoda mast held the stern of the ship up off the seafloor, allowing divers to get a glimpse of the 16-inch guns sticking out from underneath and get inside some areas of the ship.

The propellers of this ship were my favorite aspect of the wreck; they were huge and covered with marine growth. Whip corals were so plentiful, it almost looked as if the propellers were growing long, green hair, and fish lived among the coral. More reef sharks appeared and hung around, just checking us out, and we went closer to the seafloor to peek up from under the ship. Lots of guns stuck out, with barrels seemingly pointed at us, telling us, “Don’t come any closer.” Even as we racked up deco time, it was pleasant to be in the warm tropical waters, with temperatures around 84°F (28°C).

Submarines. Eight submarines were used in Operation Crossroads, three of which were sunk: the Skipjack, Apagon and Pilotfish. During Test Baker, the submarines were staged at different depths: the Skipjack at 150ft (45M), Apagon at 100ft (30m) and Pilotfish at 56ft (17m). The Skipjack was raised to be further studied, but the Apagon and the Pilotfish remain underwater at Bikini Atoll to this day.

I had already dived the Apagon on a previous trip, so I was really excited to dive the Pilotfish on this trip. Both submarines sat upright and were fairly intact. They rested at 170ft (55m) in the sand and had low profiles, so most of the dives on them were spent around 130ft (39m). Both submarines were Balao-class steel submarines, 312ft (95m) in length, with a 27ft (8m) beam and a height of 47ft (14m).

USS Arkansas. The USS Arkansas has quite a history, as it was commissioned in 1912. It was present during WWI, when the German High Seas Fleet surrendered at Scapa Flow in 1918. It also participated in the invasions of Normandy and provided fire support on Omaha Beach. In 1944, it was sent to the Pacific. Another large ship at 562ft (171m) in length, it sat upside down at 165ft (50m) in the lagoon.

The liveaboard’s cruise director let me join him on a photo dive to set up lights in some of the guns. Unfortunately, the visibility was not making the photo shoot easy, but even just seeing the lit-up scene was impressive, with the lights shining out of the gun barrels on this amazing ship.

The Arkansas was the closest ship to the Baker blast, and the underwater pressure from the bomb crushed the starboard side of the hull from below, causing the vessel to roll portside. The superstructure has never been found; it may have been crushed under the hull or blown off in the blast.

USS Lamson and USS Anderson. We also dived two of the five ships sunk by Test Able: the destroyers USSLamson and USS Anderson. Both were just over 340ft (103m) long. The Lamson sat upright, while the Anderson rested on its port side.

Built for speed, the low profile of these ships made it easy to see most of each wreck site in one dive, with depths of 120 to 165ft (36 to 50m) in the sand. The Lamson had some really neat guns on the deck, as well as a torpedo launcher, with torpedoes in place and ready to go. The Anderson’s bridge sat in the sand, making for a great view of the propellors and rudder, and the superstructure and bridge area lay in the sand.

The islands

Almost as fascinating as the wrecks is Bikini Island. On an afternoon halfway through the trip, we skipped a dive (to help off-gas) and visited the island for a BBQ, which was cooked on board but eaten on the island.

For a place that seems like the ends of the earth, I was surprised we were not the only ones there. The ship that came to pick up the island caretakers and their goods was around, as was a research vessel from Australia, with several tenders. The lagoon felt almost crowded. But there was almost some comfort in knowing we were not completely alone, far away from any other humans.

Abandoned multiple times over the years, Bikini Island felt unreal—perhaps more like an empty theater stage set, or a Disney-like spectacle, built to show what might happen after a nuclear apocalypse. Buildings still stood. Doors were open.

In the early 2000s, a land-based dive resort was set up, in the hopes of generating money for the Bikini people and to help divers to dive this unique location. But it closed several years later. Oceanfront hotel rooms remained abandoned today, and the infamous Bikini Bar was still there. Various workshops, broken-down cranes, cars and boats were now a part of the island, with greenery growing around and into them. A maintenance shed stood open, packed full of rusting tools. Rotting cardboard boxes of nails and screws were in a slow state of decay. The dive shop still had a whiteboard with a dive plan for the Saratoga on it.

We walked around, snapping photos and reveling in how empty the island felt. It was so quiet, I almost felt like I should whisper. We were not the only ones on the island though. But we soon would be.

For many years, several people lived on the island for three-month rotations, including island caretakers who were employed to do maintenance work and several employees from the US Department of Energy who continued to monitor radiation levels. Previous research had shown that short stays were not detrimental to human health. But these stays have recently come to an end, with a landing craft on the beach, loading up all the leftover supplies as well as the people who worked there.

Bikini trust scandal

These workers were supposed to be paid by the Bikini Council (which also collects payments from divers for permit fees to dive the wrecks). But in 2023, a scandal was uncovered. The once multimillion-dollar trust, set up to assist the displaced Bikini residents and their future generations, was empty.

Back in 1982, a resettlement fund of US$25 million was set up by the United States to support the residents of Bikini, who still cannot safely return to their homeland today. Another fund was set up in 1987, with funds to go directly into payments to the Bikinians, including an additional US$90 million. Several million dollars each year was given to the Bikini Council to help provide housing, food and education to Bikini descendants. This fund was administered by the United States.

In 2016, the elected mayor of the Bikini Council, Anderson Jibas, wanted control of the fund to be in Marshallese hands, not overseen by the United States, which provided the funds. In 2017, it was handed over to the Council, and over US$59 million was in the account. Withdrawal limits were lifted and auditing by the United States was concluded.

In the spring of 2023, it was discovered that less than US$100,000 remained, and that the money had been spent by Jibas, on land development in Hawaii as well as on ships, planes and apartment complexes in the Marshall Islands. There were also reports of millions of dollars being deposited into a private Bank of Guam account for “council operations,” which Jibas later denied.

The men packing their bags on Bikini Island told us they were no longer being paid. The atoll may truly be abandoned for now, other than for a few wayward scuba divers who journey halfway across the world to see this place. Yet again, the still-displaced Bikinian people seem to never be able to catch a break.

Deserted and stranded

A few islands down from Bikini Island was the island where the old runway was located. Grass grew tall over the flat area, and once again, I had a feeling of being in some sort of movie set. The airport check-in counter was still there. But there were no workers. Behind the counter were luggage tags for destinations, including KWA (Kwajalein), MAJ (Majuro) and HNL (Honolulu).

One might think for a second that we were just waiting for a delayed plane, which was a little ironic, because the last group of divers who stayed at the land-based operation did just that. Air Marshall Islands, the local airline, just closed one day and left them stranded on Bikini. It was several weeks before a US ship came to rescue them.

Is it safe?

The two tests of Operation Crossroads were only the beginning. Between 1946 and 1958, 67 nuclear weapons were tested in the Marshall Islands. The question always arises: Is it safe to dive the wrecks of Bikini and visit the island? According to research done by the US Department of Energy and Lawrence Livermore Laboratories, short visits to the area are fine. The general environment poses no radiological danger; however, consuming island-grown food (or island animals that eat island-grown food) for long periods of time might still be a danger. Don’t eat the coconuts.

Remote conditions

Operating a liveaboard in this remote and isolated location must be tremendously difficult. I walked through the store on Ebeye, where most of the food for the boat was purchased, and there were very limited options and very limited amounts of food. I would say the food was not the best I have ever had on a liveaboard, but when you consider how difficult it is to even get food, I was amazed by what the chef could do with such limited options. We had mini slider burgers and curries, and even empanadas one night. Ice cream was plentiful, and like most liveaboards, this was not a place to go on a diet.

The crew and staff of Master Liveaboards took the challenges in stride and presented a product that almost made one feel “not that remote.” Plus, the advantage of having Starlink on board helped one stay connected with the outside world. I do enjoy detoxing from screens when I am on dive trips, but there was something nice in being able to check in with friends and family back home, occasionally, over the long trip. There was a charge for this, but I felt it was completely acceptable.

All too soon, it was time to make the 30-hour journey back to Kwajalein, and we were lucky to have fantastic weather for the crossing. The day underway was spent editing photos, packing and chatting about our return trips. Back on Ebeye, we enjoyed our last night aboard and woke up on the last morning to manta rays swimming alongside the boat. Then, it was time to start the long journey back home.

Tech certification

Master Liveaboard’s Bikini Atoll itineraries require all divers to be tech-certified to the equivalent of PADI Tec 50 or higher. There is no medical care available in Bikini and only limited care in Majuro, with no hyperbaric facilities. Divers need to keep in mind the remoteness of the location and the distance they will be from medical care when planning and carrying out dives. Diving conservatively is highly recommended.

While it is certainly a time-consuming and expensive endeavor, I think visiting Bikini Atoll, diving the wrecks, and bringing back the stories from this abandoned part of the planet is important—to remind the outside world of what happened here and to prevent future catastrophes. For trained technical divers who are historical-wreck enthusiasts, it is a playground with some of the most fascinating wrecks on Earth, including their histories from before the vessels were used in Operation Crossroads and their legacy as ships sunk in peacetime, by nuclear weapons. There is nowhere and nothing else quite like it. ■

Special thanks go to Master Liveaboards for their support, and for continuing to run trips to this remote and amazing destination. For more information, please visit: masterliveaboards.com.

Reference:

Mckenzie, P. (2023, May 3). $59 Million, Gone: How Bikini Atoll Leaders Blew Through U.S. Trust Fund. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/03/world/asia/bikini-atoll-resettlement…