Travelling to the Antarctic to dive gin-clear polar waters is a dream topping many an adventurous diver’s bucket list. Farhat “Raf” Jah shares his impressions and experiences from a dive expedition to Antarctica, the Falkland Islands and South Georgia.

Contributed by

Just getting to the start of an Antarctic dive expedition is a journey in itself. It took my wife, Francesca, and I 15 to 18 hours on a Boeing 777 to get to Buenos Aires. Then, after a night in the city, a 3.5-hour flight on a Boeing 737 brought us to the southern tip of South America and the town of Ushuaia. Here, we made a mandatory two-night halt in case our baggage had chosen a different route. We were now within 100 miles of Cape Horn and the southernmost tip of South America.

Ushuaia was pretty, but it consisted of a series of overpriced, odd-looking hotels and restaurants set on the side of a hill. We wandered around the streets trying to make sure that our legs worked, stopping in cafes to drink real coffee while looking out at the Beagle Channel, with Chile as the backdrop.

En route

Boarding the MV Plancius did not go quite as planned. A crew member had been sick, and the Argentine authorities wanted to quarantine the ship. So, we hung around Ushuaia, drinking coffee and waiting for news. Thankfully, the ship’s agent managed to negotiate mass inoculation instead. We met up to hear the expedition leader and her deputy explain that all was well, and we could now be bussed to the ship.

With no idea about what really went on, we felt slightly uneasy, but were soon steaming out of Ushuaia while we attended safety briefings and had dinner on board. I later went out on deck and stared at Argentina to the north and Chile to the south; the excitement was palpable, as skuas and other seabirds circled the ship in the endless twilight.

Preparations and safety

Morning unveiled an unbelievably calm south Atlantic Ocean. We prepared our kit and listened to interminable briefings on everything from how to get boots on to boarding a zodiac. As divers, most of this was old hat, but briefings are vital and compulsory, so we listened closely.

More important were the repeated briefings on dive safety procedures. There is so much that can go wrong, so nothing can be left to chance—or worse, assumption. We assembled on the ship’s bow and thoroughly tested our kit. Check, check, check and check again—then take it apart. While kitting up, we saw a fin whale breach near the ship, followed by a pod of orcas ambling alongside our vessel.After lunch, we had a series of lectures of varying quality on the Falkland Islands and geology.

Falkland Islands

A good cruising pace brought us into the following morning, and we steamed around the outer edges of the Falkland Islands. We passed through a gap called Wooley Gut at 6:45 a.m., and I stood on the bow and peered down at penguins and dolphins on either side of the vessel.

Our first dives were check-out dives. Using a procedure that was to become a habit, we loaded our zodiac with dive gear. It was then craned over the side, with our dive guide aboard, by a trio of competent and friendly Filipino crewmen. We embarked via the gangway, and within 30 minutes, there were fat, black-and-white Comerson's dolphins swimming around our zodiac.

Excited to get wet, we struggled into our kit and rolled into the waters with a depth of about 10 metres. Francisca was my dive buddy, and we checked buoyancy, cameras and general movement before winding our way through the kelp and bearing right, seeing crabs, fish and an octopus along the way. The water was a pleasant 10°C, and I was able to dive with 3mm neoprene gloves.

What amazed me about the Falkland Islands was the sheer amount of sea life down amongst the kelp. Everywhere I looked, I saw a crab or a nudibranch or a small fish. We descended to 16m, played with some seals, and kept looking around, because there was something to see everywhere. As is often the case, our allotted 45 minutes of time were suddenly up. We surfaced, and Jerry, the Plancius dive team leader, picked us up.

Carcass Island. With time to spare, we landed on a slipway at Carcass Island, and walked, still donned in our drysuits, to a small settlement, which, to my surprise, was operated by friendly Chileans. While I sipped on a welcome mug of tea, I was entertained by gentoo penguins, plus a vulture flying overhead. But sitting there created an unusual problem: We started to overheat in the sun! Our drysuits and Weezle undersuits coped well with the South Atlantic Ocean's frigid waters but posed a problem on land. It was easily fixed by jumping into the nearby bay to shed some heat.

Saunders Island. Reboarding the Plancius, we lunched before arriving at the “neck” of Saunders Island where we were soon back in the water. We had done our check dives. We had ironed out any kinks. This now was real expedition diving. No one had been here before, and every buddy team had to make their own decisions.

We reached the rocky bottom at 15m and found our way through even thicker, but more bunchy kelp. The visibility was four to six metres, and wherever I looked, I saw life. Lobster krill, fish, starfish and multiple nudibranchs, made for an excellent dive.

Port Stanley

That night, we steamed to Port Stanley—capital of the Falkland Islands and a charming small town populated by people from around the world—before departing for South Georgia. We broke down our scuba kit to make sure that it would not be damaged if we hit rough weather.

With 20-, then 30- and finally 40-knot winds, I thought the sea swell was under two metres—but the third officer said it was a 4m swell, causing rougher seas. As the Plancius rode the swells, there were yet more lectures, but the weather held as we made good time at a steady 12 knots.

South Georgia

Tern Island. Nearly three days later, we were diving off Tern Island in South Georgia. We had passed the convergence and the water temperature was down to 2°C. Our thermal layers were fine, but some of the group started to suffer cold hands. However, with fur seals swirling all around us and coming up close to say hello, freezing hands were soon forgotten and we had a magical dive.

South Georgia had us alternating diving and landing. Some of the dives were less spectacular than others. Francisca and I went down to enjoy the 10 to 30cm visibility. We held hands and felt our way along the side of the wall for ten minutes before binning the dive. The experience was not lost, however, as we spent the rest of the time snorkelling with the seals.

Following this dive site, we landed at coves named Salisbury Plain, Prince Olav Harbour, and St Andrews Bay. These were packed with penguins and breeding male fur seals, the latter being rather snarly and snappy if anyone ventured too close.

Quarry Wall. Later in the trip, we dived in the afternoon at a site called Quarry Wall. I was without a buddy and so joined my friends Elmar Schanz and Stevie Macleod. Stevie was one of Dubai’s veteran and most experienced dive technicians, and the only person carrying more spare parts than me. On the dive deck, he had blown a wrist seal and replaced it quickly. We thought that all was well until we rolled off the zodiac. Stevie surfaced suddenly and shouted: “I’ve got water in my suit!” He swam quickly back to the zodiac and said, “You two dive together.” There was no time to debate the matter. With 2°C water in his suit, he had to get out of the water immediately.

Elmar and I had never dived together before, but “needs must,” I suppose. So, we dropped down to 20m and moved along the rock wall. We wound our way through the kelp with an occasional communicative nod and were treated to a plethora of sea stars and small molluscs. We ended the dive after 31 minutes, with seals playing around us in 7m of water—all very nice, but my video was annoyingly out of focus.

Coopers Bay. After an evening halt in Grytviken, our last day in South Georgia loomed. The non-divers were offered a zodiac cruise, but I opted for a gamble dive. If the dive was rubbish, I would snorkel; if it was good, it would be worth it. Francisca decided she just wanted to snorkel, so I ended up diving with Gavin Walker in Coopers Bay.

We descended off a small, unknown islet and hit the bottom at 12m. I had not tied my ankle velcro straps tight enough, so I was leg-buoyant, and scrabbled around, trying to take photos, stay warm, and maintain some form of level. It was a lot of work, but it was enormous fun, as we enjoyed a whole three metres of clear visibility!

After 24 minutes, I suggested we end the dive, since my fingers hurt with the cold. Gavin kindly agreed, and we ascended to three metres, where we dutifully did a three-minute safety stop. I cursed in my regulator as my painful fingers screamed at me, and a swell meant we had to hang on to some kelp to stabilise ourselves. We had descended to 13m and lasted for an impressive 27 minutes. Gavin had used 60 bar, and I, some 120.

South Orkney Islands

As soon as we were done, we had lunch on the ship, which navigated through a series of icebergs. South Georgia disappeared as we turned southwest towards the South Orkney Islands. After taking some photos on deck, I was soon asleep in my cabin.

We generally had two days at sea between every set of islands we visited. This was time spent writing up our experiences, cleaning our land kit for biosecurity reasons, and double-checking our dive kit. While on deck, we watched numerous whales blow on either side of the Plancius while the sun set, albeit slowly, and more icebergs became visible.

As we travelled southwest, the atmosphere onboard changed from trepidation to excitement—we had made it out of South Georgia without a single injury. The weather held, and the Southern Ocean was flat-calm, which meant we could maintain a speed of 12 knots with all three diesel generators running. The phrase we heard from the bridge was, “All’s well—3DG full ahead.”

Coronation Island. One morning, we steamed through fields of thick ice and arrived at Coronation Island in the South Orkneys. We were inside Antarctica and yet still so far from the actual continent. Our soft-spoken Russian captain wove his way between the icebergs with supreme skill. Penguins sat on the ice, seals sunned themselves, and we marvelled at the weather.

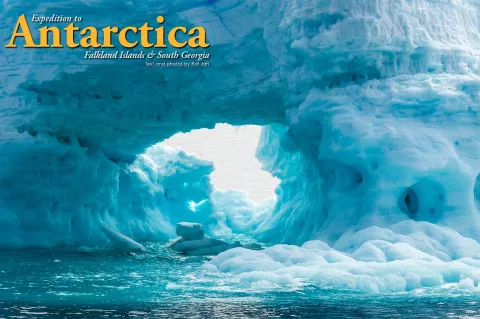

The ice was so thick that we could not land on the shingle beach, so our dive team leader decided to dive an iceberg instead. We dropped in and circled a medium-sized iceberg; the depth was well over 100m, and so we had to maintain perfect buoyancy.

Gavin and his wife, Petra, disappeared first, followed by Francisca and me. The water was green and murky, yet the iceberg was melting and creating a layer of clear water next to it. The water temperature was between 0°C and 2°C. I tried to photograph some ice with a stone suspended in it, but with a strange current running, I found myself finning like mad to travel around the iceberg. After 15 minutes, we had seen enough and surfaced calmly.

Once we had clambered back into the zodiacs, we cruised around in the stunning sunlight before alighting on another smaller iceberg for a team photo. Standing there, I literally felt as though I had made it to the highest passes of Nepal again before we headed back to the Plancius for lunch and coffee.

Elephant Island. We were told that there was a slight possibility of making it to Elephant Island, depending on sea conditions and time. If the sea stayed calm and we could set off by 3 p.m., we had a chance of making it. The atmosphere on the Plancius become electric. The idea of seeing the beach where in 1915 Sir Ernest Shackleton was forced to leave his men while he sailed to South Georgia to find rescue was beyond belief.

The view from the porthole showed an apparently calm sea (you never can really tell in the Southern Ocean), and the Plancius maintained its sedate 12 knots all morning. We were getting closer and closer.

Then, just as we approached Elephant Island, the sea started boiling with humpback and fin whales as they surfaced, blew, and dived again and again in front of us. I lost count of how many there were. In the foreground, hundreds of chinstrap penguins filled the sea, while Antarctic terns and prions filled the sky as they dived for food. I had never seen such a proliferation of marine life. The captain decided that we could stop, and turning the Plancius in slow circles, played with the big mammals for an hour.

It was time to head on to Elephant Island, and we headed into the bay opposite Cape Wild and dropped anchor, so the crew could launch all ten zodiacs. Motoring slowly, we viewed Point Wild from both sides, then closed in to see the tiny beach where Shackleton’s men had spent 16 weeks. They lived under two boats for four months, eating seals and penguins and drinking Bovril. With steep cliffs and a glacier behind, and caves and a spit of land in front, their camp would have been exposed and tiny. It was an incredibly emotive place.

On the far side, we found a leopard seal playing with the zodiacs. It swam from inflatable to inflatable until, bored, he bit into a zodiac full of Germans. There was mild consternation as the boat deflated and some passengers had to be transferred to other boats!

Paulet Island. We left Elephant Island, and a day later, were at Paulet Island. Francisca was not feeling great, so I joined Gavin and Petra once again. But once on the boat, Petra realised she had no air, so I dived with Gavin. I was getting used to Gavin’s completely unruffled style.

We were advised to use a surface marker buoy (SMB) if the current was running. We rolled in, as the current was streaming along at three knots. Paulet Island was a place in which I had no desire to get lost at the surface, so I deployed my SMB immediately. We dived along on a steep slope, with rounded rocks, limpets, pale lobster krill, isopods, sea squirts, sea spiders and sea cucumbers, as well as numerous orange spongy things, a large white nudibranch, some small worms, a few entry holes, loads of urchins and some small fish.

My regulator started to become hard to breathe through, so I pulled in a hefty breath and a bunch of ice shot into my mouth, making the regulator a lot easier to breathe through. Too easy, and in fact, it was starting to free flow, so I took out the regulator and switched to the second one. Gavin turned the air off to the free-flowing regulator, but with poor buoyancy, I ended up on the surface. I ducked down to find Gavin, and we continued on the dive.

After a while, Gavin turned my valve back on again, so that I could at least see, rather than guess, my contents gauge, and we dived on calmly. By the time we finished, we had moved over half a kilometre. I ran low on air, signalled to go up, and ascended. Gavin did not follow, so I went down to get him. He then followed; in the confusion, however, I dropped my GoPro camera and Francisca’s torch. Apart from these losses, the dive had been a great success.

Zodiac driver and commercial diver Chris had to help me de-kit. My fingers were so painful that I had to put them into my Arctic warfare mittens and massage them, and it was a full five minutes before they were of any use.

Continuing on, we landed at rocky Paulet Island and saw a massive Adélie penguin colony near the ruins of an old stone hut, with an incredible frozen lake on the far side. We watched the penguins slither over the ice and waddle around in their comical penguin manner. Someone spotted what looked like a man-made path leading up a hill, reminding us that this was the island that Shackleton wanted to reach. Apart from having supplies, the landscape would have been sensational for a camp—much better than the tiny, horrid space on Elephant Island.

Brown Bluff. In the afternoon, we headed to Brown Bluff in Antarctica, a pillar of volcanic ash mixed with basalt. The cliff behind looked like the Grand Canyon, and we enjoyed summer-like weather with brilliant sunshine. We dived on an underwater ridge off Brown Bluff, with two icebergs, one grounded and one floating. We swam along the ridge and down to 14m, spotting life everywhere: seaweed, red algae, amphipods, brittle stars, limpets and more. There were penguins on top of the ice, but not under, and we were excited to be diving on the Antarctic continent itself. Soon after we ascended, we were on the continent!

A68-A. Our expedition leader decided that we should try and get to A68-A—which was, at the time, the world’s largest iceberg and a section of the Larsen Ice Shelf that had broken off. Our skipper found it, and the weather held perfectly. We cruised for about 90 minutes along A68-A, before coming into fast and brash ice. The ship circled the bigger of the ice floes and bashed its way through the smaller ones, the hull clanging against larger lumps.

We pushed ever southwards, and the ice thickened, with Adélie penguins scrabbling out of our way onto the pack ice. Eventually, we saw a single emperor penguin, then a second. I took several photos, knowing that my chances of making it this far south again were slim, and I would probably never see one of these magnificent birds in its natural habitat again.

It was time to enter the green water and savour its great visibility. Petra had a cold, so I dived with Gavin again. We had around three metres of visibility, but plankton was found everywhere. Visibility improved at depth, and there was more life on this dive than on any other dive we had done since the Falklands.

Yankee Harbour

The morning saw us arrive at Yankee Harbour, a name whose provenance stumped us all. I decided to dive with the Walkers. We had crystal-clear blue water with five metres of visibility and 1°C water temperature. This does not sound like much, but 5m of clear and sun-illuminated waters made the dive seem like paradise. The two-degree warmer water made such a difference. I photographed fish again, krill, and more fish.

This was the best of Antarctic diving. With that, I was done. This dive would be too hard to beat. I washed my kit and later that day, went ashore with the non-divers. I sat on a stone in Horseshoe Bay, watching whales breach and penguins natter. The expedition was over.

There remained the small matter of writing reports, editing photos, and sailing for two days through the Drake Passage to start the journey home—“small beer” compared to what we had done and seen. ▪️