The Norang valley is clothed in pale green birch leaves and sprouting grass, and the mountains rise majestically up in to the clouds. The mountain tops are completely snow covered, and at the foot of the mountains are large masses of stone from both new and older landslides. A small red car with four divers drives slowly down the valley stopping excitedly at each small lake to check the visibility and condition on the bottom.

Contributed by

As early as the 1880s the Norang valley was a popular tourist magnet among the European aristocracy and upper classes, authors and mountaineers. The expeditions of the latter often had the aim of being the first to climb the surrounding mountains. It often happened, though, that the great climbers (after several attempts using different routes and many hours hard work) finally reached the summit – only to find small cairns which the local youth had already built long ago.

The formation of Lyngstøl lake

The grandiose nature attracts many tourists through the valley but among we divers it is best known for the Lyngstøl lake. It was formed on the night of 26 May, 1908, when a large landslide occurred from the mountain Keipen (1218 meters above sea level). The mass of rock filled a large area 2-300 meters wide and ”several men” high. The event was highly dramatic, down in the village the next morning a cloud of stone dust was seen to emerge from the valley opposite. The villagers had already packed and were prepared for the annual spring climb to the nine farms in the upper pastures of Lygnstøl. Luckily nobody had yet gone up there.

The stream had been blocked by the landslide and within one day everything on the bottom of the valley was covered with water. The farms lay just across from this land-slide area, and after the flooding there were only the roofs of the huts and some trees sticking out of the water. The roofs have fallen in long ago and the trees in the shallow water have fallen over; however, in the deeper water the forest of trees still stands quite upright. At a few places in the water one can see how the trees have hung out over the old course of the stream. The old road, the stone walls, bridge and one of the road markers lie exactly as they did 95 years ago. Farming in the Norang valley finally ceased in the fifties when food concentrates became available.

Diving around the house foundations

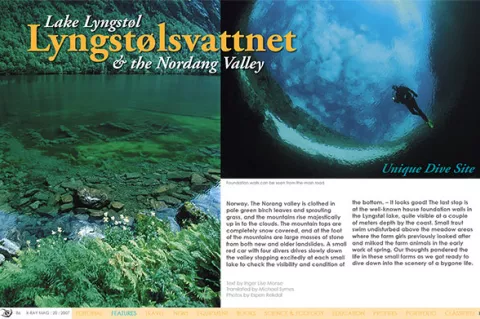

We have parked at the north end of the water (nearest to Øye). The amount of lead has been adjusted and found to be well suited to the reduced buoyancy in fresh water. The dive reveals little more round the house foundations than can be seen from the road on a wind-still day but of course it is much more interesting to see it at close range in a diving suit. In the upper part there appears to be an old home made ladder laying along the wall, but we leave it alone in order not to destroy anything.

A small fresh-water snail was observed on top of the foundation wall. We don’t know so much about these, but we easily recognise the small trout and char that swim quickly past. Some also lay hidden down in the grass. The meadow is bounded by a small stone wall, and the road passes by just below it. Unfortunately the well-known gate is no longer intact. Perhaps a diver has tried to open it. Or perhaps all those years under water have had their effect. After having had a little look around the meadow, the greater part of the dive was devoted to photographing the house foundations. This is not the place for deep water diving, our biggest logged depth being only 6 meters.

In Walt Disney’s world?

For our second dive we made our base at the information board which has been put up by the water. We swim straight out from the shore and over some fallen trees before we reach the standing forest. The scene which meets us could have been taken from one of Walt Disney’s tales. From the branches of the grey trees hangs something which, at a distance, looks like a thick layer of cobwebs and other strange stuff. It looks like the forest round the house in Hansel and Gretel! The green grass on the hill looks as if it is melting together with the ”heavens” in a beautiful green ”sunset”. The atmosphere is quite trold-like, but with these colours and the play of the sunbeams in the water it is not at all sinister, just fantastically beautiful. Closer up, it can be seen that the growth on the trees is algae which appears to be thriving well, together with a small amount of dead grass which the current has carried down through the water. For a short while among the trees it is certainly quite a special feeling to hover weightless round in the tree tops – together with small fish!

Freshwater growth

The branches are partially covered with different fungi/algae, some in an old-rose tint, some brown and others more transparent. On a few broken pieces we see fungus-like growths with orange ”flowers” and green stalks. They are not much more than 2 cm in height so it is necessary to look carefully in order to find them. Earlier in the summer the grass which covers most of the lake bed has small yellow flowers. Again, it is necessary to look carefully in order to see them. Using a lamp makes it generally easier to find these small things.

Conditions on the bottom

In most places the bottom is completely overgrown by green grass. Beneath it, like the rest of the bottom, is a thick layer of mud. For successful diving (and photographing!) good control of buoyancy is therefore required. Care is also necessary when considering the fragile trees which still stand upright. They can tolerate very little and therefore break and crumble away if the diver gets too close. Not really so good, for in fact it seems a miracle that they are still standing upright after 95 years under water.

The old road and bridge

The old road which now lies on the lake bottom of Lyngstøl was, in fact, the new road when the land-slide occurred in 1908. It was established because of the big problems with rock- and snow-slides from Keipen. Construction of the road was carried out by workers brought in from outside. Maintenance of the road was thereafter carried out by the farms to each of which was delegated a portion of the road which had to be kept free from rocks and secured against slippage of the road itself. After the last big land-slide a new route had to be carved out, and it is here that the road still remains.

There are screes, stick-fencing and road-edging stones to be found along the road in Lyngstøl lake. Right across from the bridge we also found a mile-stone. It is still standing as it was originally, and the text is still quite legible ”RodeNo3”. The stone marks the boundary between the responsibilities of two farms for their respective stretches of road. After having studied the stone for a while I look at the sediments on the road – was there something moving there? A three-centimetre long tube moved slightly again. A closer look showed it to be the house of a larva of one of the large spring-flies. The larva glues small stones together to form a thin tube which it drags around everywhere it goes. This house makes a good protection in the form of camouflage against the mud of the bottom. However, the small tracks it makes is a little give-away!

We swim further under the bridge which is built of large, flat stone blocks. Under the bridge we see that our bubbles break against roof and trickle up between the stones. Coming out again from under the bridge we enjoy the sight of how the sun’s rays make a shiny carpet of the small bubbles which float quickly to the surface. We swap places to swim under again just to see it once more.

Misty waters

The visibility in Lyngstøl lake is very variable. The amount of precipitation plays a part but the greater part of the flow of water is filtered through the mass of stones on the bottom of the valley. This makes the water much clearer than one would expect for freshwater in a ”normal” valley. With a large amount of precipitation the more rapid flow of water will cause mud to be dragged up from the bottom and spread up into the lake. Material from land-slides can also hit the water and spread mud-clouds (even though the vegetation along the lake indicates that this has not happened for some time). The sun and light conditions will also affect the visibility in the water, either by directly influencing the growth of algae or by illuminating the particles in the water.

We have dived here in conditions of both good and bad visibility but as a rule it has been clear either over or under the cloudiness. A couple of times we have also seen clouds of silt floating in thin horizontal layers between the trees. I think that is incredibly charming as it gives the diving place greatly different atmospheres – and thereby gives me different impressions.

Solahølen

Before returning home we decided to take a dive in the deep Solahølen (in English: the sunhole). It has got its name from the sun which, in the summer, appears here early in the morning. The cows have also realised this: they often overnight here, perhaps in the hope of enjoying the morning sun? They look at us, these crazy people who clumsily waddle down to the water. Passing tourists stop to see what is happening, but we can se that they are smiling a little to themselves.

In Solahølen we experience a fantastic visibility. Snowdrifts which hang out over the water form a beautiful frame round the stony bottom. There is only a thin layer of mud on the mass of stones. This is probably due to the fact that there is a good through-flow of the water: a small stream runs in from Ura lake in addition to the flow through the rock-slide. An enormous large rock lies in the middle of the deep hole. We hope that a similar one will not come rushing down when we are down there… For the hole has been continually formed by new rock-slides. These rush down to the bottom and hit against the other side of the hole. Much of this new material in this way has then piled itself up against the road.

By following the stream further down over towards Stavberg lake we arrive at a snow-bridge. This can be experienced every year, but melts away during the Summer. In the shadow opposite, however, lies a miniature glacier which survives every summer. After a short side-spring we can boast of having been on a ’glacier trip’!

Trip possibilities

We still return to the Norang valley. It is especially the diving that is of the greatest interest, but I greatly look forward to the day when we have time to investigate the surrounding mountains. Slogen, Skruven, Keipen, Litlehorn, Jakta and Smørskredtindane are all tempting objects for trips, even if some of them require some experience of climbing and that one uses the proper safety equipment. Relatively easy glacier trips can also be undertaken, but a local guide should be engaged.

Under the open sky

For our visit to the Norang valley we choose to overnight in tents, as it gave us the best opportunities to follow the changing light conditions. This is of course important for the photographer in that different motives appear at their best under different light conditions. After spending a pleasant evening in sleeping-bags around the camp fire we decided to sleep outside. Not long after the chatter had died away we heard small squeaks above our heads, and it was first shortly after that we could see dark shadows dancing across the heavens. It was small bats! A short moment after that little surprise we fall asleep at last, where we continued to dream of the forest and farms beneath the water. ■

Published in

-

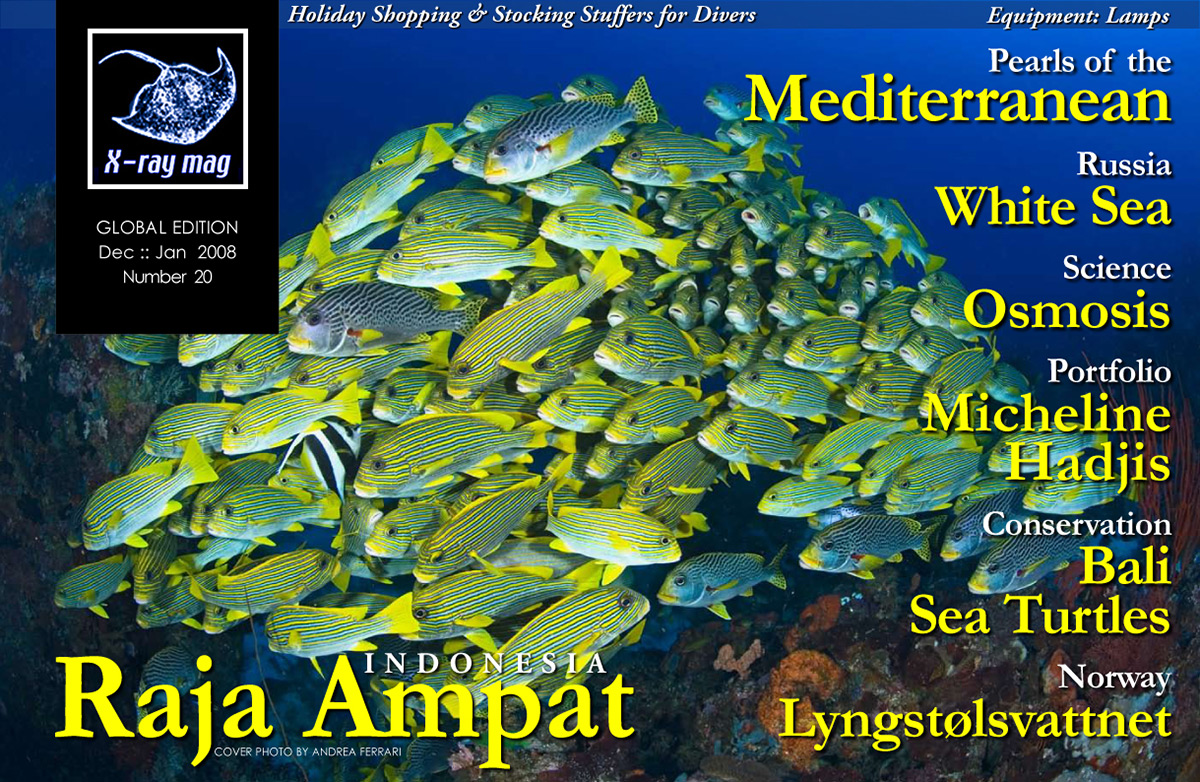

X-Ray Mag #20

- Läs mer om X-Ray Mag #20

- Log in to post comments