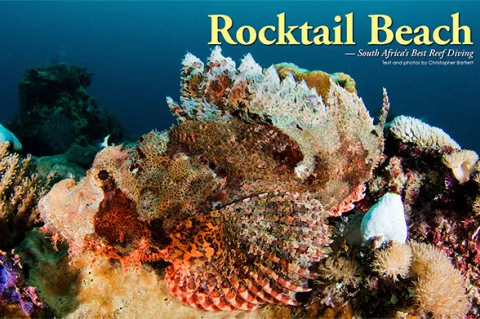

South Africa's Rocktail Beach

South Africa’s dive scene is well-known for its shark diving. Yet, there is a great deal more to see underwater off the coast of the old continent, towards the border with Mozambique, at Rocktail Bay.

Contributed by

Factfile

Christopher Bartlett is a widely-published British underwater photographer, certified FGASA African field guide and dive writer based in London.

He leads photographic trips to Papua New Guinea, Southern and Eastern Africa, Mexico and the Maldives, providing free workshops and tuition.

For more information, visit: www.bartlettimages.com.

HOW TO GET THERE

Fly to Durban via Johannesburg, Cape Town, Dubai or Istanbul and then either drive up or have a transfer arranged. It is a four-hour drive to Coastal Cashews. Or you can fly to Richards Bay, and then transfer or drive up. It is a three-hour drive to Coastal Cashews from there.

DIVING FEES AND EQUIPMENT

Dives cost 530 ZAR per dive. Cylinders and weights cost 150 ZAR per day (not per dive).

ACCOMMODATION

For 2017, accommodation costs 2,900 ZAR during the low season (February, March, May, June, September, October, November) and 3,290 ZAR during the high season (January, April, July, August, December).

DISTANCES

Driving in Sodwana Bay is one hour south, Aliwal Shoal is 4.5 hours south, and Protea Banks is 5.5 hours south.

TOPSIDE SAFARIS

Safari combinations are plentiful. There are a handful of excellent Big Five game reserves and safari lodges in KwaZulu-Natal, less than two hours away. Or you could fly to Johannesburg, Nelspruit or Skukuza to visit the legendary Kruger National Park.

TOUR OPERATOR

This trip was arranged by Indigo Safaris (www.indigosafaris.com). Email Ines on ines@indigosafaris.com and she will put together a dream trip for you.

In South Africa, there are year-round opportunities to see oceanic blacktip sharks, bull sharks, scalloped and great hammerheads, black and whitetip reef sharks, and ragged-tooth sharks (aka sand tiger sharks in the US or grey nurse sharks in Australia). There are seasonal baited dives with tiger sharks, and whale sharks are present in the Indian Ocean. Off the Western Cape, one can find broadnose sevengill sharks, blue sharks, mako sharks, shysharks and, of course, great white sharks. But the Indian Ocean hides some gems beyond this plethora of sharks, with some of the country’s best reefs to be found off Rocktail Beach.

Part of iSimangaliso Wetland Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1999 and a Ramsar site since 1986, Rocktail Bay sits amongst the towering coastal dunes and lush coastal forests of the Maputaland Marine Reserve. Meaning "a miracle" or "something wondrous" in Zulu, the word iSimangaliso comes from when some of King Shaka's subjects were sent to the land of the Tsonga, and returned to describe the beauty that he saw as a miracle. The biodiverse reserve combines untouched coastline with coral reefs, freshwater lake ecosystems—including South Africa’s largest freshwater lake, Lake Sibaya—coastal forests, wetlands, grasslands and woodlands.

Getting there

Getting to the place is an adventure in itself. After driving four hours north from Durban, you pull into a car park at a small cashew factory and shop to be met by one of the guides from Rocktail Beach Camp and transfer to a four-wheel-drive open game viewer for a 30-minute drive along sandy tracks through the forest up to the coastal dunes, which are amongst the tallest vegetated dunes in the world and home to an array of wildlife and birds.

Upon arrival, my kit bag was taken to the dive centre and I went to check out my room. Rocktail Beach Camp has long been considered the premium dive lodge in the country, and it was easy to see why. The open plan bar-lounge area, dining room next to the pool, wraparound veranda and raised viewing deck are simple but classy. Set off a trail in the forest, the rooms, of which there are 17, are tented suites with sliding glass doors. When the canvas is rolled up, the view from the inside of the honeymoon suite over the canopy to the ocean is superb.

Dive centre

I went for a walk down to the beach, 10 minutes away, and met Michelle and Clive Smith, the couple running the only dive centre in the area. Clive was pulling one of their 7.2-metre RIBs out of the sea with a tractor, as you do in these parts. Apart from three people in wetsuits, the beach was deserted, and stretched endlessly in both directions without a soul on it, golden and pristine. It is a stunning location, and offers diving year-round as most of the resident fish remain on the reefs throughout the summer and winter seasons.

The main seasonal differences are water temperature, visibility and the special migratory humpback whale sightings. During the summer months, there is a noticeable increase in shark sightings, including grey reef sharks, zebra sharks, blacktip sharks, hammerhead sharks (scalloped and great), tiger sharks, whitetip sharks; as well as sightings of guitar fish, round ribbontail rays, honeycomb rays, sharpnose stingrays, blue spotted rays and occasional butterfly rays.

We talked about the following day. I was to be their only diver and Michelle wanted to take me to Gogo’s and Yellowfin, her two favourite spots. As it was August, they had not seen any sharks for a while, but there were rays around and some big resident groupers. I had had a good fill of sharks down at Aliwal Shoal on my last dive trip, so I was keen to check out the reef life.

Diving

Despite the choppy surface conditions, the launch was easy, at a shallow reef forming a natural RIB-sized harbour close to the beach. We were at the site in a matter of minutes. I wasn’t expecting much in terms of visibility. The sites are mostly shallow, generally not deeper than 18m, and the wind was up. But as I rolled in, I could see the large reef top about 10m below me.

Gogo’s. The topography of Gogo’s makes it an ideal haven for fish life, with collapsed features, gullies, overhangs, crevices and swim-throughs. Gogo’s is considered the “show piece” of diving at Rocktail Bay. From the reef formations to the abundant fish life, there is something for everyone on Gogo’s. A school of silvery slingers danced over the hard and soft corals as trumpet fish hunted, and anthias swam into the gentle current.

I had been promised a potato bass, and within a few minutes, a female cruised by. Michelle waggled her finger at me and shook her head “no”, then spread her arms and puffed out her cheeks, hooked a thumb to the left and turned that way. I followed her lead.

Hovering over a bommie, unfazed and regal, was the biggest male potato grouper I had seen for some time, nearly 2m long and going nowhere. His stern face was in stark contrast to my beaming smile. I had been underwater for less than 10 minutes and I could see the riches of Rocktail were abundant. The grouper was so not going anywhere, and I snapped away for a while as Michelle looked for shrimps. Each to their own.

Old Grumpster ignored me. I was insignificant, not worthy of his attention, but I stayed and watched a cleaner wrasse nibble around his eye from less than an arm’s length away, until a hawksbill sea turtle swam past. It swam slow enough for me to overtake it and get some frontal shots as it cruised the reef, no doubt looking for a tasty snack.

Michelle had found an impressive honeycomb moray eel, which was swaying around, more out of its crevice than in, as if it was being charmed by a tune that was inaudible to us, putting on a show to the slingers and anthias in the vicinity. I was trying to work out what tune it might be dancing to, when I heard it.

Not eel-charming music, but a whale song. And, my word, it seemed close. And then there was a reply. Michelle and I both looked around. The whale song was so loud, it seemed like these giant marine mammals must be close enough to see. But apart from a few thousand fish, the only mammal I could see was Michelle.

Then the duet started. One high pitched, one deep back and forth, the sound reverberating through the water and through me. I have been in the water with humpbacks to photograph them before, and of course they sang, but not like this, and not this loud, and it was getting louder. Were they going to swim by us?

Trying to find them would prove fruitless. It is very difficult to work out which direction a sound is coming from underwater, so we just drifted gently, peering into the distance in opposite directions as the concert went on for 10 minutes, until the end of our dive. It was such an incredible experience, we raved about it to Clive during the surface interval.

Yellowfin Reef. Next up was Yellowfin Reef, another pretty dive site with good topography of sink holes and collapsed features, and plenty of corals as well as an abundance of fish life. More shoals of slinger, blue-banded snappers, surgeonfish and fusiliers hung in mid-water as there are numerous pinnacles at this site that attract the schooling fish in significant numbers. During the season, one can spot grey reef sharks passing by, just off the reef.

A juvenile green sea turtle made an appearance, and resting placidly on the sand was a 2m wide round ribbontail ray, half-covered in sand, sheltered by the reef on one side. Getting close to the sand, facing the ray, I inched forward, extending the pauses between my inhaling and exhaling as far as I could, turning my head away on the exhale to avoid spooking the ray. The ray filled my camera frame, with its sand-covered body and blotchy head, as it eyed me.

Topside excursions

The dive centre has hot showers, shampoo and shower gel, so there is no need to go back to your room after the dive if you are hungry, other than to just soak up the view and or give yourself another dose of wow. Most of the time, dives finish early enough for divers to either go on an afternoon guided or unguided excursion into the forest to look for duiker, reedbuck—both antelope species—and some of the 300-odd bird species found here.

The guided excursions are on foot or in the four-wheel-drive game viewer and are free, as are the sundowner trips to Lake Sibaya, and full-day trips there. Lake Sibaya has one of the highest concentrations of hippos. You can also plan a morning off and visit Tembe Elephant Park, a Big Five reserve, 50 minutes away. In turtle nesting season, there are also trips to look for either turtles laying their eggs, or the eggs hatching.

As we had made two long dives, I missed the game drive departure, so I took a leisurely late lunch, sorted through my photos and had a chat with the bar staff. Before I knew it, it was time for a sundowner on the deck with some new arrivals. The pre-dinner nibbles came out, as did another sundowner (just to make sure the sun went down properly) and then it was time for a top-notch three-course dinner. After all that, my giant bed was calling.

More diving

Pineapple Reef. The next day, we headed to Pineapple Reef, named after the pineapplefish that are often seen there. Pineapplefish are a very rare find in this part of the world, but are sometimes found with a close look under certain ledges, so I took a macro lens with me. Seems like the fish didn’t know I was coming (or maybe they did) and had gone off on a day trip.

Still, there were plenty of other subjects for me to photograph, including Durban dancing shrimp, white-banded cleaner shrimp, an orangutan crab and a bright orange frogfish. And there were, of course, three more potato bass, which are not quite macro subjects unless they are getting a clean. These three were not, so they were happily gliding around the reef in blue water, whilst my fisheye lens was on the boat.

Never one to tire of potato bass, I switched lenses on the boat and asked if we could do it again. Michelle explained that they sometimes saw four there, and that in the warmer months, manta rays, whale sharks and loggerhead turtles were sometimes seen. But it was mid-winter, and the shark and manta action was quiet, much like farther down the coast where even on baited dives, tiger sharks would only appear from December to early May.

The bass were still there, doing their bassy thing, this time in front of the right lens. Another honeycomb moray eel was half out of its hole, so I stopped to take some shots of it as Michelle stayed out of my field of view, with her buoy line. She was off to one side, checking for pineapplefish again.

The next thing I knew, there was a frantic tugging on my fin. I thought some choice expletives in my head. Couldn’t she see I was busy? Then I thought, “Hmm. She’s been doing this for 15 years. She clearly can see I am busy. It must be important.” So, I turned around and a very animated Michelle communicated to me that there had been a 4m tiger shark behind me (no doubt curious about my camera settings), but that it had swum off as she made eye contact with it.

It was a most curious event, and a subject of much discussion, as it was widely thought that the tiger sharks migrated away from the KwaZulu-Natal coast in the winter (between May and November) for unknown reasons, as they were never seen. Except on our dive, which took place in mid-winter. Two weeks later, a dead humpback whale appeared close to Aliwal Shoal, and it was estimated that up to a dozen tiger sharks were seen feeding on it over the weekend. So, they are most definitely around, they were just invisible—unless you happen to have a dead whale on you, or take photos of honeycomb moray eels.

Other dive sites

In addition to the three sites I dived, there are another dozen dive sites in the area, which are primarily shallow dives. There are also a couple of deeper sites, including Blood Snapper, which descends to 50m.

In the worst month of the year, I had had a great time. Rocktail Beach’s diving was excellent, with healthy, vibrant reefs and plentiful fish. The Camp lived up to its reputation as the premier dive lodge in the country. The service was irreproachable, top drawer, and supremely friendly. I can’t wait to go back to dive in the summer.

Activities for non-divers

One great thing about Rocktail Beach are the options available for the non-diving members of the family. Besides the morning and afternoon nature activities and day trips to the lakes and Tembe Elephant Park (which is a wilderness area requiring four-wheel-drive expertise, not an African Disney World), the dive centre also runs Ocean Experience trips, either for snorkelling or just observing from the boat. One of the dive sites frequented by ragged-tooth sharks is so shallow that you can snorkel with them. Dolphin sightings are also common, both bottlenose and the shyer spinner dolphins.

Seasons and conditions

In the spring and summer from late September to May, water temperatures rise from the colder winter temperatures to between 21-23°C in spring and up to 25-28°C in summer. Visibility averages around 18-25m and can be as good as 35+m.

During the summer months of December to March, pregnant ragged-tooth shark sightings are very common, as the sharks move northwards from the Eastern Cape area up to southern KwaZulu-Natal, where they mate. The females then continue northwards to these warmer waters and rest for approximately three months during their gestation period, before heading back to the colder Eastern Cape waters to give birth to their pups. The other magical summer sighting is of female loggerhead and leatherback sea turtles coming ashore at night to lay their eggs during nesting season from October to March.

In the autumn and winter months from June to early September, water temperatures drop to an average of 20-23°C in winter, with 19°C being the coldest recorded winter temperature. Visibility drops to an average of 12-18m but can occasionally get up to 20-25m. August and September are traditionally the windiest months of the year. The diving is still good, but the wind may cause surface conditions to become very choppy. Diving continues unless the swell becomes too big.

The highlight during winter is the arrival of the humpback whales on their annual migration to Madagascar between June to late August, and then returning southwards to the Antarctic between September to November. The whales tend to travel farther out to sea on their migration up to Madagascar, as these are mainly adults and adolescents on their homeward journey. We get to see the whales much closer to shore when they travel with their babies. ■

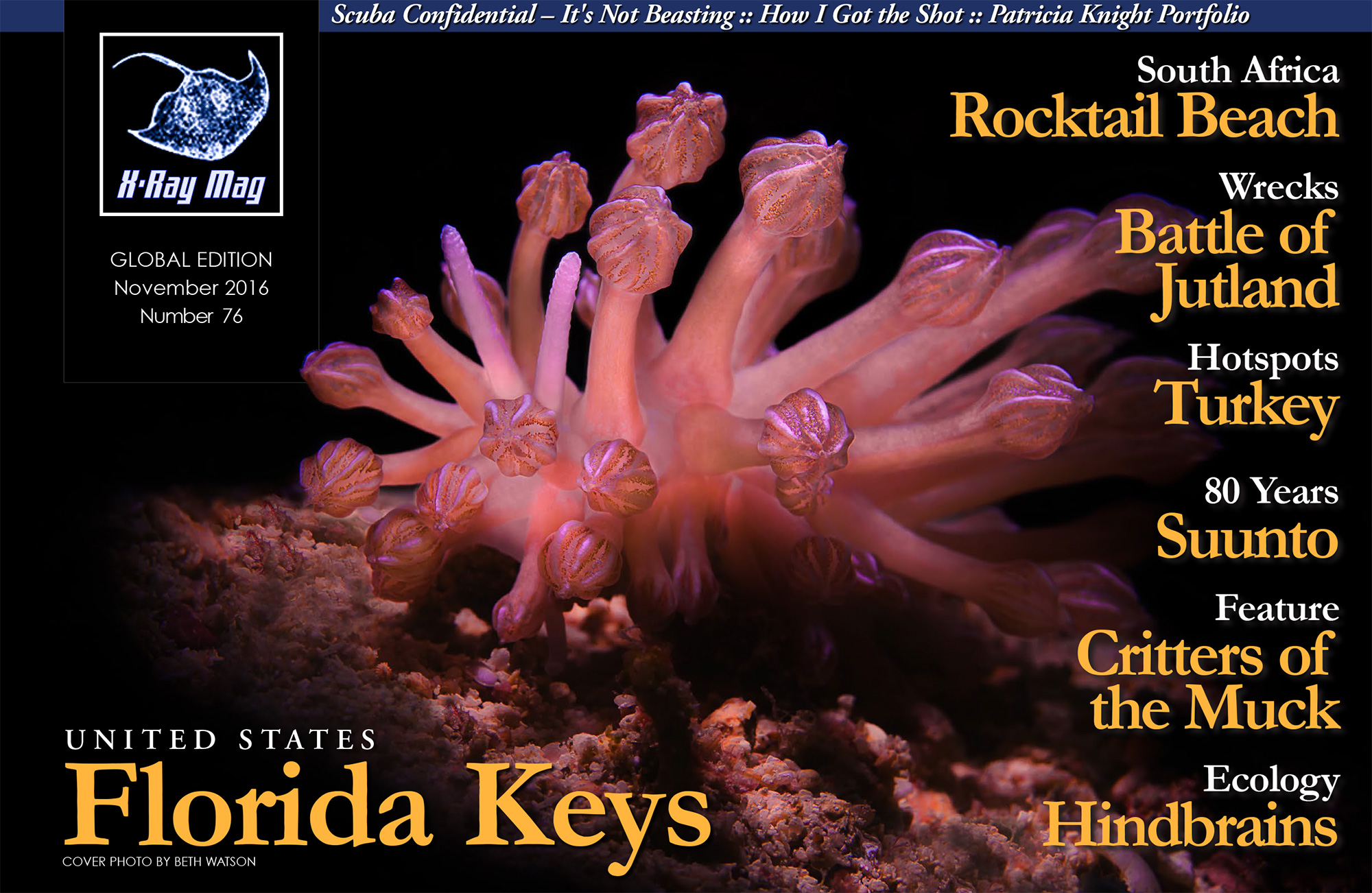

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #76

- Læs mere om X-Ray Mag #76

- Log ind for at skrive kommentarer