Sardines, Dolphins, Sharks... South Africa!

Since times long forgotten, the promise of treasures such as diamonds, gold and platinum has attracted adventurers from all over the world to South Africa in the vain hope of finding new riches.

Contributed by

Indeed, South Africa has long been a destination for adventurers world-wide since olden times. Hopes of finding new treasures, the excitement of the hunt and the pursuit of long held dreams heat up the mind of the explorer, painting fantasies in rainbow colors on the African plains. The desire to get away from the drudgery of everyday and familiar places inspires even the most inveterate home bodies and mamma’s boys. Of course, divers have the adventurous spirit in the blood, too, from the time they are born. This is exactly why the unexplored treasures of this country are attractive and magical to everyone and are the basis of our journey to this exotic world.

In 1487, the explorer Bartolomeu Dias of Portugal became the first European to reach the most southern tip of Africa. King John II of Portugal named it the Cabo da Boa Esperança, or Cape of Good Hope, because it led to the riches of India cherished by Europeans and traders. Later, Jan van Riebeeck established a new midway station (now Cape Town) at the Cape of Good Hope on 6 April 1652 for the Dutch East India Company. Soon, colonists from the Netherlands, France and Germany started to arrive.

Modern South Africa is an incredible combination of people of different races, cultures, religions and languages. In this society of diverse social classes there are 11 different languages spoken including Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda, Xitsonga, Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa and isiZulu. Thus, it is very symbolic that the nation’s motto is !ke e: |xarra |ke, or “Unity in Diversity”—literally, “Diverse People Unite”. The airlines of the Emirates offered us special weight terms as divers carrying extra heavy luggage with dive equipment. They rushed us over to this orange land of beauty, this mysterious country. What was waiting for us down there?

Catch the sardine

Each year, at the end of June and the beginning of July, the sardine migration travels along the south coast of the Republic of South Africa. Millions of sardines collect into huge schools and follow each other somewhere for important sardine business. Whales, dolphins, sharks, seals, sea birds, fishermen and divers cannot fail to attend this huge fish party. The place, where for a short time so many different sea animals collect together, is a big rarity on this Earth. It is an unique opportunity to watch the animals’ behavior in natural conditions, get very closely acquainted them, and take good shots. It is exactly for this reason that we are going to the “Wild Coast”, to Mbotyi River Lodge (www.mbotyi.co.za)—a very convenient place to organize a dive expedition.

Each week, there are meetings of about 50 people, madcaps and adventurers from all over the world. They are equipped up to the teeth with the most modern photo and video equipment and technology and are ready to dive even into the Devil’s horns just to test themselves and to capture some good photographic fortune from the sea. Businesslike South Africans from companies such as Sea-Air-Land (www.sea-air-land.com) and African Watersports (www.africanwatersports.co.za) provide top-end marine speed boat charters with experienced captians. Two microlight vehicles go out every day starting at sunrise to search the ocean for marine creature activity.

Action

This is the place where dolphins, whales and sharks hunt, corral and pack sardines together into a heap, or a bait ball, to make a convenient arrangement for dinner. Sea birds swoop down from the sky into the water when they see that the sardines are accumulated into a dense ball. Dinner is ready. Speed diving from altitudes of 20-30 meters above, the birds dive into the water—rowing with their wings and rolling by twisting their heads—pursuing the sardines with great enthusiasm.

The “Wild Coast” is refered to in this manner because the currents, waves and wind vary unpredictably and change quickly. From time immemorial, this place has had a bad reputation among seamen. Many brave seamen and good ships lie permanently on the bottom of the sea here. Getting to the sea from the surf is a dangerous adventure in Mbotyi, even with a very skilled skipper. In the beginning, the whole team tried to push the boat out as far away from the coast as possible as soon as it was possible.

All the crew members were dressed in life jackets—death clings to everything—but the only possible thing for us to cling to was the boat. Everything depended on the filigree skipper’s skill, who should, just like a surfer, slide the boat along the powerful ocean tidal waves—foam crested and roaring—rolling along the Wild Coast. Those who were unlucky and had an unskilled captain got soaked with streams of salty water, their equipment washed overboard and their boat overturned. But, we, not having experienced this everyday, left with the dawn and headed out to sea anyway. Struggling with the waves and rolling around in the surf, we drove on out to the sea in search of sardines.

The hunt

“The key to success is harmonious command work,” said Nic de Gersigny, already on his sixth Sardine Run expedition. “The skilled pilot in the motorized hang-glider flying above the sea all day long observes the weather, finds places of congestion of sardines and whales, dolphins, sharks or diving birds, and by radio set, directs our boat to that location. From a boat, we can only see the congestion of the birds in dense flight circling above the specific spot in the sea. But the birds often arrive later, following the whales and dolphins who are leading the formation of the sardine bait balls. Therefore, support from the sky is very important.”

At last, our boat is flying over the tops of the waves, falling into water troughs, and speeding towards our adventures. Our purpose (as guests in this neck of the woods) is to capture the sardine dinner on film. Finally, we found the first flock of diving birds. The sea was boiling from birds splashing and dropping out of the sky and down through the surface of the sea. It looked very serious, like a massive air attack and bombardment of the ocean. Involuntary ideas popped into my head, like how not to get under the birds’ bombardment—God forbid that a diving bird would cut my head open with a sharp beak! It seemed quite possible that one could lose one’s life under this intense bombardment.

Dolphins rushed in and zipped around the birds—their harmonious hunting groups jumping and leaping out of the water. As fast as it was possible, we were falling out of the boat with a loud command from our skipper. We grouped up and started the plunge

All around us, the water was filled with continuous high-frequency squeaking—the voices of the dolphins. Somewhere below us, for a second, was the giant school of sardines shining and disappearing into the depths.

A few of the dolphins were a little curious with us. The chattering dolphins communicated among themselves. They did a circle around our group. It was visible, that they discussed us with each other, examined us more closely, and then departed after the sardines.

The sardines were gone again. They moved too quickly for us. All that was left in the water were the sparkling fish scales of the sardines—remnants from the dining table of the dolphins.

Then, the sharks came up from the depths to meet us; they were as curious as the other inhabitants of the sea. They turned directly under us, so we had to nestle our backs against each other more closely. We thought that if we presented ourselves as a large sea animal, we could frighten off the sharks. But some of the divers who were already approached by the sharks at close range, had to push them away aggressively with a long sharp stick. The sharks went back into the depths, and we got back onboard.

While we were in the water, all the activity had moved at least a kilometer away already. All the events here happened so quickly that not only was it necessary to have surpassed skill, experience, and knowledge of the biological behavior of animals but great luck as well to appear in the right place at the right time. Furthermore, one needed to be able to manage to take pictures of all the events underwater.We trained, over and over again. We jumped into the water at other locations where birds and dolphins were hunting. We pursued whales. By means of towing an empty plastic bottle, we beckoned a photo session with a new group of sharks. We gained experience and skill with the constant and instantly varying underwater conditions, and continued on this course six hours per day.

The next jump with the camera into the water resulted in an unsuccessful pursuit and, apparently, a group failure. All the divers, one by one, came back up into the boat, and I, the last one in line, looked back and around, being afraid of unexpected sharks.

The current carried me to the side of the boat. Everyone was onboard by now, and I was heading there as well. But as not to be pushed, I swam more closely to the boat. I lifted my head upwards, and I saw a bird diving directly towards me.

Forgetting about everything, I pulled my head back down under the water and lifted the camera. It was happening! A small school of sardines gathered as the bird flew like a torpedo through the thickness of the water.

I took several shots by throwing up my arms camera in hand, like the heroes of the old Westerns did with their pistols, not even lifting the camera to my eyes. Six shots fired off, and by some miracle, I got my first picture of a bird flying underwater.

All of a sudden and unexpectedly, the long-awaited action began. The water boiled around me. Dolphins started rushing in. The thickness of the water was ripped apart by the breakers from birds piercing the water. Unfortunately, my camera overheated and broke before finishing writing all the images I took onto the CF card.

A few exciting minutes later, and I found myself once again in an absolutely empty ocean—all the recent events already seeming like a fantastic mirage. If not for the pictures remaining in the memory of my camera and the sardine fish-scales floating around of me, it all could have been a dream.

We knew in advance that our success with catching images of the diving sea birds was doomed, so our focus and confidence was transferred to dolphins, sardines and whales. They became photo models for us. Our day came when we dived all together twice.

The school of sardines, ever-changing in external form and outline, moved around a depth of no more than five to seven meters—slowly or quickly, the bait ball would swell. Bubbles exhaled by the divers gathered the sardines into a rotating circle dissipated by an attack by dolphins only to gather again in an almost perfect geometrical sphere.

We took more pictures. Frightened by our air bubbles, the dolphins gathered in a group away from us. It was visible and audible how they discussed the situation with each other—what were these strange finned-feet entities doing near their sardines and why were these beings preventing them from having a snack?

Having stopped the discussion and made a decision, they swam up quickly onto different sides of us and the bait ball, and with well-trained hunting formation and loud shouts (underwater high-frequency squeaks), forced the whole sardine ball to move swiftly away, cutting it off from us. The dolphins swam at reckless speeds, dashing into the bait ball and snatching sardines from different angles.

I tried to catch up with the bait ball. I kicked my fins very hard. Then, I lifted my head and saw a dolphin with a brilliant sardine in its teeth take off away from the fish stew and swim directly towards me.

No, we had no time to collide, he was too skilled underwater and dodged a blow as easily as the passing of a thought, and he did not even forget to swallow the fish he had just caught.

Hunting directed by dolphins reaches the top of perfection and is, indeed, one of the most harmonious activities of these supreme sea inhabitants.

It seemed that the sardine hunt lasted only about ten minutes, but when we come back to the boat, overflowing with impressions, our skipper told us that we had been in the water for one and a half hours! So quickly does time fly during the Sardine Run. One and a half hours of activity and my 4GB memory card was filled with pictures.

Whales

We devoted the whole next day to photographing whales. Our pilot searched for whales, informed us of their direction of travel, and then, we set off to pursue them. With a speed worthy of the Special Forces, we jumped into the water as we traveled at the same speed as the whales, and kicked our fins like crazy in hopes that they would swim up to us more closely.

Whales are like people, absolutely different. If one of them dived far away and more deeply in order not intersect with us underwater, others were absolutely indifferent to us. The third individual showed discontent and a lot of annoyance with the small men. The fourth showed surprising curiosity. We especially liked the humpbacked whales. They adored jumping out of the water, spraying enchanting fountains, waving chest fins and clapping their huge tail fins on the surface. The dull round ends of their noses were so photogenic, too!

But the most amazing event happened when, tired and out of breath, we sat down for a minute to have a rest in our boat. On this occasion, we had already made five to seven unsuccessfully attempts at pursuit, jumped into the water, tried to follow the whales, rowing with all the force we could muster, but made not one picture of our passionately favored sea giants. All the whales were completely immersed underwater or departed too quickly. And here, in that one moment when we relaxed, reflecting on the vanity of a diver’s life and of the hunters of whales, was, literally within two to three meters from our boat, a huge head silently rising out of the sea.

The whale stayed there and looked at us closely; it was obvious that he wished to examine us further. We were so amazed at this show, that we were simply dumbfounded and had not stirred at all, being afraid to frighten away the huge entity. We were not pulled at all to our cameras, and simply enjoyed our silent dialogue with the whale.

Perhaps, the whale had bad eyesight and consequently swam up more closely to have a better look, or, maybe, he wished to smell us? We would never know.

Some long moments later, he noisily inhaled, as though he was grumbling something to himself under his nose and dived, slapping his wide tail fin on the water. Yes, the slap was so strong that the entire boat has covered with a down-pour of salty rain. We never saw the whale again, having not had a chance to ask him in time what it was that he was wanted.

The Big Five

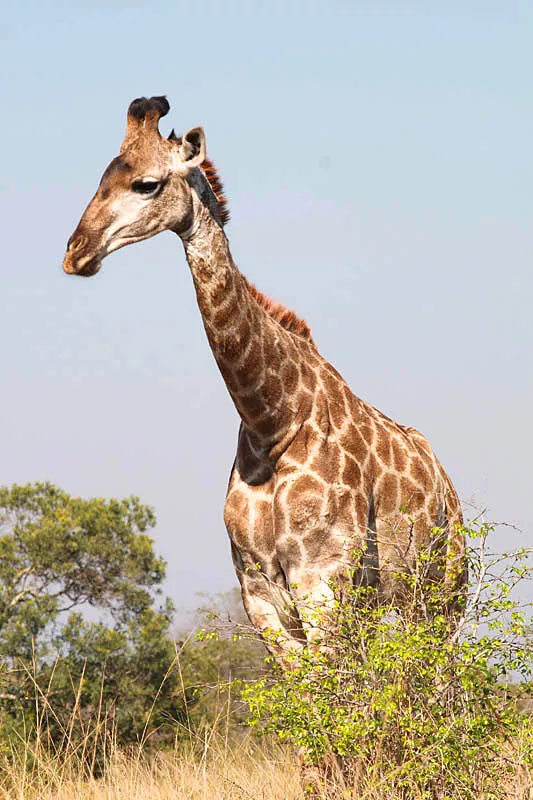

To travel so far, to the edge of the Ojkumeny, and only dive for sardines and whales would be truly unfortunate. Even for keen divers, it is interesting to see and get acquainted with not only the underwater world, but also the overland world in this part of the planet. Following the trail to the treasures of the Republic of South Africa brings one in contact with the unique wild nature kept today only in national parks. The private Game Resort Phinda—which in translation from the Zulu language means “jungle”—has 23,000 hectares of South-African jungle. It is located within 15 minutes of air travel from the coast. But when we landed here, we understood that we had entered an entirely different world.

We chose to go to Phinda because it was near one of the best natural parks of the Southern Hemisphere. It meant that we would find true professionals of the game business, we thought. Surely, they would show us the Big Five: a lion, a leopard, an elephant, a rhinoceros and a buffalo, living in a natural environment. And we were not mistaken!

With a hat that could have been Indiana Jones’, some warm blankets, a little marula (a local sweet drink), binoculars, two cameras, a powerful four wheel drive open off-road vehicle, and an armed ranger on a bumper, we headed out to a meeting with new adventures in the real bush—this was a South African safari not to miss!

It was exclusive. We went through jungle to track a lion, hiked through the high grasses of the savanna to track a cheetah, and cautiously, being afraid to approach too closely, photographed the elusive rhinoceros and a buffalo, participated in a night pursuit of a leopard and finally sensed and smelled an elephant running very close to us.

Afterthoughts

Two weeks of adventure seemed to fly by in a breath—so quickly, easily and with immense fascination. We had become active participants in an absolutely unique on the planet underwater event—the great migration of sardines and the big hunt for them by thousands of sea birds, sharks and dolphins. We lived and breathed South Africa, where it is still possible to see and photograph dozens of jumping whales. For a long time in our memories, will our minds’ eyes remain in the great canyons, roaring falls, bright juicy colors of the wild woods, sensing the lions’ hunt seizing us down to our bones, hearing the night roar of the lion—the tsar of the animals—seeking the leopard—the king of the night jungle—and the fastest predator, the cheetah, eternally chewing and breaking into high speed chases all along the way. We saw elephants, rhinoceroses and self-assured, unshakable buffalos.

Now we can authoritively state that Southern Africa is definitely one of the best places in the world for diving and for photo safaris with wild animals. The nature of South Africa and its wild inhabitants are the most priceless treasures, indeed, national treasures of this great country, and subjects of fascination for modern adventurers.

We left the South African Republic with a feeling of deep satisfaction—we opened ourselves to a new world and have the strong desire to return here once again to follow the migration of the sardines along the Wild Coast! ■

The editor wishes to express his most sincere gratitude to:

Ship captain, Paul Warren Von Blerk, expert on whales and sharks of the Wild Coast; Microlight pilot, Larry Eschner, heavenly slow mover, who gave us a wonderful opportunity to see the Wild Coast in an absolutely new perspective; Emirates Airlines, (Emirates.com) for allowing 10 kg extra weight for underwater equipment free-of-charge; The management of ССAfrica (CCAfrica.com) for granting us an opportunity to get acquainted with the wild nature of Phinda Privat Game Reserve.

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #25

- Læs mere om X-Ray Mag #25

- Log ind for at skrive kommentarer