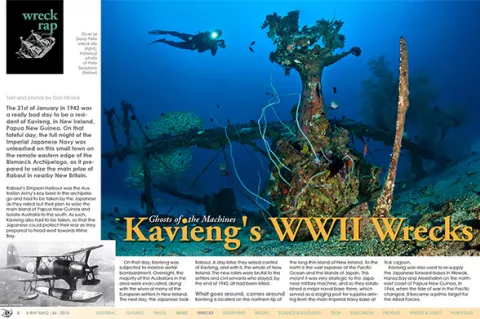

Ghosts of the Machines: Kavieng’s WWII Wrecks

The 21st of January in 1942 was a really bad day to be a resident of Kavieng, in New Ireland, Papua New Guinea. On that fateful day, the full might of the Imperial Japanese Navy was unleashed on this small town on the remote eastern edge of the Bismarck Archipelago, as it prepared to seize the main prize of Rabaul in nearby New Britain.

Contributed by

Factfile

Don Silcock is based in Sydney, Australia, and is the Asia Correspondent for X-RAY MAG.

He travels widely in Asia and his website (www.indopacificimages.com) has extensive information and image galleries on the diving in Papua New Guinea and other great dive locations across the Indo-Pacific region.

Rabaul’s Simpson Harbour was the Australian Army’s key base in the archipelago, and had to be taken by the Japanese, as they rolled out their plan to seize the main island of Papua New Guinea and isolate Australia to the south. As such, Kavieng also had to be taken, so that the Japanese could protect their rear as they prepared to head west towards Milne Bay.

During that day, Kavieng was subjected to massive aerial bombardment. Overnight, the majority of the Australians in the area were evacuated, along with the wives of many of the European settlers in New Ireland. The next day, the Japanese took Rabaul. A day later, they seized control of Kavieng; and with it, the whole of New Ireland. The new rulers were brutal to the settlers and civil servants who stayed; by the end of 1943, all had been killed.

What goes around, comes around

Kavieng is located on the northern tip of the long thin island of New Ireland. To the north is the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean and the islands of Japan. This meant it was very strategic to the Japanese military machine, and so they established a major naval base there, which served as a staging post for supplies arriving from the main Imperial Navy base at Truk Lagoon.

Kavieng was also used to re-supply the Japanese forward bases in Wewak, Hansa Bay and Alexishafen on the northeast coast of Papua New Guinea. In 1944, when the tide of war in the Pacific changed, it became a prime target for the Allied Forces.

Douglas MacArthur, the mercurial Commander of Allied Forces, decided against invading New Ireland as he implemented his “island hopping” strategy to regain control of the Philippines. Therefore, his commanders decided that Kavieng would have to be neutralized through air raids, led by squadrons of B-24 Liberator heavy bombers. Those raids began on 11 February 1944 and continued over the next few days, effectively destroying the Japanese base and its fleet of seaplanes.

The air raids on Kavieng were followed up on February 16 when six squadrons of bombers and strafers took off in search of a 14-ship Japanese convoy reported to be heading for the area. Three of those vessels, the Sanko Maru, an unidentified submarine and Subchaser #39 which was guarding them, were found near Three Island Harbor at New Hanover, the large island to the west of Kavieng.

War records from the time show that the Sanko Maru, a 5,461-ton tanker, was anchored in shallow waters with the partially submerged submarine next to it, while the Subchaser #39 cruised nearby guarding the two vessels. B-25 Mitchell bombers targeted the Sanko Maru with numerous 500lb shells and the ship was quickly destroyed and sank; while the Subchaser #39 was pursued and ultimately ran aground on a nearby reef, where it became target practice for the bomber crews.

A tremendous photograph taken by the rear camera of Rita’s Wagon, one of the attacking B-25s, captured another Mitchell Bomber dropping a 500lb bomb on the Subchaser #39 while the Sanko Maru burned in the background. As for the submarine, it was later identified as a Type C midget version, when bombers from the 500th squadron returned to the area the following day and dropped two 500lb bombs on it.

The bombs missed their target, but the submarine was lifted out of the water by the impact and flames were reported, so a sinking claimed. Later evidence indicated that the submarine was actually scuttled by the crew to prevent it from being captured. The aerial attacks continued through to February 21. Several other Japanese ships suffered similar fates.

Ghosts of the machines

Nearly 70 years have passed since those February days of destruction. A visit to Kavieng today will reveal few visible signs of the Japanese occupation. The town has long since returned to the typical “Somerset Maugham South Sea island port” it is often described as—which can probably be loosely translated as friendly, laid-back and quiet!

But beneath the waters are the ghosts of WWII that draw scuba divers from all over the world to experience and photograph the remains that litter the area–particularly the many aircraft wrecks for which Kavieng is famous for. Those wrecks range from the superb Deep Pete Japanese biplane laying upside down in the blue Pacific waters off Nusa Lik island to several other WWII aircraft laying at the bottom of the harbor—victims of surprise air raids which caught them at their moorings.

Then, throw in the shipwrecks at New Hanover and a unique opportunity to dive on the Type C mini-submarine, that sits upright and completely intact on the sand near Tunnung Island, and it’s easy to understand why New Ireland is a “must have” in so many diver’s logbooks.

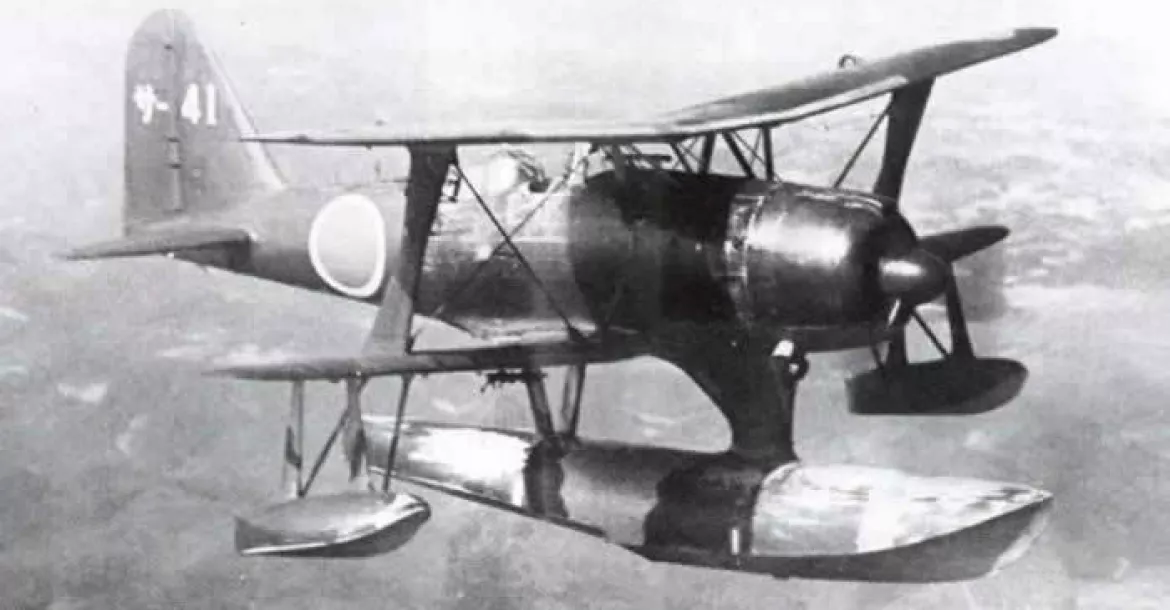

Deep Pete

The wreck of the Deep Pete is the most photogenic of the WWII aircraft wrecks in the Kavieng area and by far my personal favorite. The plane itself is a Mitsubishi F1M float-plane, which was designed and built to be launched by catapult from battleships, cruisers and aircraft tenders; and to be used for reconnaissance missions. It also saw service as an impromptu fighter, dive bomber and patrol aircraft.

This specific model was a biplane with a single large central float and stabilizing floats at each end of the lower wing. Apparently, early versions suffered from poor directional stability in flight, and were prone to ‘porpoise’ when on the water, which may explain why the wreck is actually there.

The name “Pete” is derived from the way the Allied Forces identified Japanese aircraft during WWII, as the actual naming convention was often both difficult to understand and pronounce. The Japanese gave two names to each aircraft; with one being the manufacturer’s alphanumeric project code, and the other the official military designation. So, the Allies used code names instead, with men’s names given to fighter aircraft, women’s names to bombers and transport planes, bird names to gliders, and tree names to trainer aircraft.

The wreck lies on its back, with the remains of its main float sticking up, on flat white sand in 40m-deep water—hence, the name “Deep Pete”. It is located on the western side of Nusa Lik (small Nusa) Island which, along with Big Nusa Island, provides the shelter for Kavieng’s harbor. As it is on the Pacific Ocean side of Kavieng, diving it on an incoming tide means that the visibility is often exceptional and usually in excess of 30 metres.

Although its tail is broken, its biplane shape is remarkably still intact, given the relatively lightweight and fragile nature of the aircraft. What makes the Deep Pete so photogenic is the resident school of yellow sweetlips that stream in and around the wings, and the batfish and barracuda that patrol in the clear blue waters above the wreck.

At just 31 feet long and with a wingspan of 36 feet, Deep Pete is not a big wreck. However, given its depth of 40 metres and the spare profile of the dive, there is rarely enough time to fully explore it, so at least two dives are required to fully appreciate and photograph it.

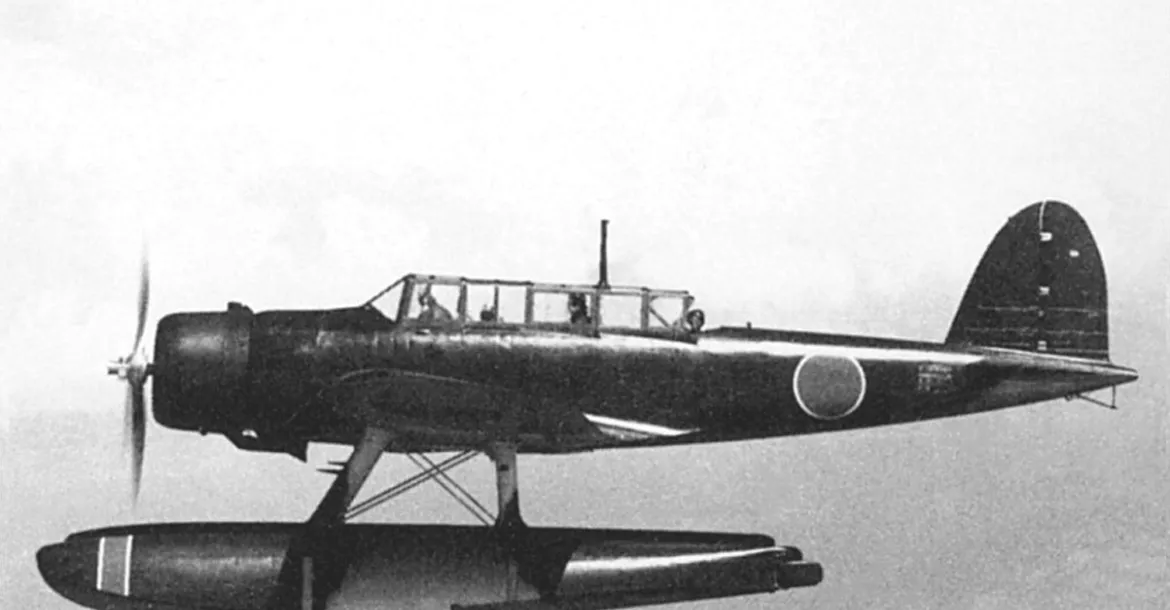

The Catalina

The wreck of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) PBY Catalina A24-11 lays at 20m depth near the entrance to Kavieng’s harbor. The Catalina flying boat was developed by the U.S. Navy in the 1930s as a long-range patrol bomber. Although slow and somewhat ungainly, Catalinas served with distinction during WWII—both in the role they were designed for, and as a very effective way of rescuing downed airmen. Their ability to land on water meant that they could be used to quickly and effectively rescue crews that had gone down in the Pacific and, in fact, have been credited with saving the lives of thousands of aircrew.

This particular PBY A24-11 was on a mission to attack Japanese forces in Truk Lagoon on 15 January 1942 and had taken off from Rabaul with six other RAAF Catalinas. They had landed at Kavieng, which was still under Australian control, to take on fuel before heading north into the Pacific. After refueling at Nusa Island, the Catalinas took off again but one of A24-11′s wing bombs accidentally exploded when it hit a swell during take-off, killing the crew and causing the plane to sink rapidly.

The wreck of the A24-11 was discovered in 2000 by the legendary Rod Pierce, skipper of the MV Barbarian, who also discovered the B17F Black Jack and S’Jacob wrecks. What Pierce found were the engines and parts of the aircraft such as the wing and landing gear in one main location—being the heaviest parts, they sank to the bottom in the same location. Part of the rest of the plane have scattered across the seabed as a result of the destructive force unleashed on the plane at such close quarters when the wing bomb exploded! Located as it is near the entrance to Kavieng’s harbor, the Catalina is best dived on an incoming tide.

Wreck of the Sanko Maru

Located just off the fringing reef of Tunnung Island, to the tip of New Hanover, are the wrecks of the Sanko Maru and the Type C midget submarine sunk during the Allied aerial bombardment of northern New Ireland in February 1944. The Sanko Maru was an armed freighter and apparently one of the “Hell Ships” used by the Japanese to transport prisoners of war in the Philippines under the most appalling conditions. At just under 400 feet long, it is a quite large wreck and lies on its starboard side in 22 meters of water.

Located on the island's southern side, the Sanko Maru is swept by the rich currents of the Pacific Ocean that run down the northwest coast of New Hanover, and thus, is covered in rich soft corals and gorgonian sea fans. The sheer density of the marine growth on the Sanko Maru is simply stunning and it would rate as a 9 to 10 on my personal “wreck scale” were it not for the visibility, which rarely exceeds 10 meters—probably because of the runoff from the nearby islands.

The damage from those 500lb bombs is clearly evident and the wreck has been stripped of its propellers and boilers by salvage divers many years ago. The wreck is easy to dive, with the upward-facing side of the ship in just six meters of water, making safety stops very easy. The Sanko Maru warrants a lot of exploration, but often does not get the attention it deserves because the star of the show is the nearby Type C midget submarine.

The midget submarine

As the story goes, the midget submarine lay undisturbed just 50 meters away from the Sanko Maru–until 1987, when it was discovered by accident by Papua New Guinea diving legends Kevin Baldwin and Bob Halstead. Halstead was diving the Sanko Maru from his liveaboard the MV Telita. Baldwin, who was on board for the trip, decided to swim out from the wreck to see if any debris had fallen on the sand, and must have thought he had won the lottery when he swam straight into a Japanese midget submarine!

Baldwin found the submarine in excellent condition, complete with its periscope and twin counter rotating propellers, but missing its torpedoes. Significantly, the main hatch on the conning tower was open, reinforcing the theory that the crew had scuttled the submarine back in 1944 when it came under attack by the B-25s. Ironically, the limited visibility in the general area meant that the salvage divers who had plundered the Sanko Maru had missed what is probably the only diveable midget submarine in Papua New Guinea—and possibly anywhere else!

The Imperial Japanese Navy built a total of 76 midget submarines for combat use between 1934 and 1944. Originally, they were designed to be carried by larger Japanese ships and deployed in the path of an enemy fleet, where they would disrupt its operations with torpedo attacks. However, during WWII, the submarines were deployed for special operations against ships in enemy harbors, including the infamous 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the 1942 raids on Sydney, Australia.

There were three versions with the original Type A displacing 46 tons and 78 feet in length and armed with two torpedoes. Driven by battery-powered electric motors, the Type A was capable of high speeds of up to about 20 knots, but with a very limited range. The prototype Type B and production Type C submarines were fitted with a diesel engine to recharge their batteries. Although no Japanese records on the Type C’s survived the war, it seems clear that the Sanko Maru was probably the “mothership” for the New Hanover submarine.

Diving the submarine is very easy as there is a thick rope laid out between it and the mast area of the Sanko Maru. It sits bolt upright on the sandy seabed. The conning tower and the twin propellers have become home to a variety of marine life and sea whips, making the submarine very photogenic.

Diving the Ghosts of the Machines

There are a few options available if you want to dive the ghosts of the machines detailed in this article (and the many others in the area). Both Lissenung Island Dive Resort and Scuba Ventures dive the aircraft wrecks around Kavieng on a regular basis. If you want to dive the wrecks of New Hanover, your best bet is to either sign up for Lissenung’s annual exploratory trip to the area which usually includes dives to the Sanko Maru and the midget submarine as part of the itinerary. Alternatively, check out the itineraries of Alan Raabe’s MV Febrina and Craig de Wit’s Golden Dawn liveaboards—both do the Kavieng and New Hanover area on a regular basis.

I personally based myself at Lissenung Resort to cover both the aircraft wrecks and to participate in the exploratory trip which was really great. However you do it, make sure you do—these are unique dives! ■

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #66

- Læs mere om X-Ray Mag #66

- Log ind for at skrive kommentarer