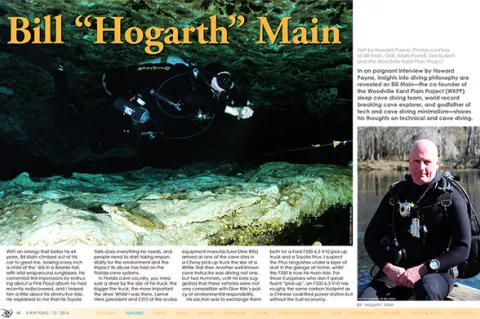

Bill “Hogarth” Main is the co-founder of the Woodville Karst Plain Project (WKPP) deep cave diving team, a world record breaking cave explorer, and godfather of tech and cave diving minimalism. With an energy that belies his 64 years, Bill Main climbed out of his car to greet me, looking every inch a child of the ‘60s in a Beanie hat, with wild wraparound sunglasses.

He cemented first impressions by enthusing about a Pink Floyd album he had recently rediscovered, and I teased him a little about his diminutive ride. He explained to me that his Toyota Yaris does everything he needs, and people need to start taking responsibility for the environment and the impact its abuse has had on the Florida cave systems.

Contributed by

In Florida cave country, you measure a diver by the size of his truck: the bigger the truck, the more important the diver. Whilst I was there, Lamar Hires (president and CEO of the scuba equipment manufacturer Dive Rite) arrived at one of the cave sites in a Chevy pickup truck the size of a White Star liner. Another well-known cave instructor was driving not one, but two Hummers, until his boss suggested that these vehicles were not very compatible with Dive Rite’s policy of environmental responsibility.

His solution was to exchange them both for a Ford F350 6.3 V10 pick-up truck and a Toyota Prius. I suspect the Prius languishes under a layer of dust in the garage at home, whilst the F350 is now his main ride. For those Europeans who don’t speak fluent “pickup”, an F350 6.3 V10 has roughly the same carbon footprint as a Chinese coal-fired power station but without the fuel economy.

So, when Bill Main arrived to meet me at Florida cave country’s most famous and popular dive—Ginnie Springs—in a tiny Toyota Yaris, the irony could not have been more perfect. As a world record breaking cave explorer, the co-founder of the WKPP deep cave diving team and a man whose middle name has become a byword for considered minimalism in technical diving, the Yaris was a perfect metaphor for his entire “less is more” philosophy.

HP: Tell us when you started diving and what it was like for you in the early years.

BM: I started diving in 1966, maybe early ’67. I did my Open Water Course with NAUI—it was more of an apprenticeship back then. I made my first cave dive at night in a sideways shaft at 200ft in a quarry in around ’69. It was all single tank stuff. We only got twin tanks in ’72, with just a single regulator. Twin valve manifolds came shortly after that. There was no formal cave training back then. We just worked things out as we went along, and made the things we needed that didn’t exist.

HP: So you have been cave diving 45 years this year. Congratulations! Some of those early big dives must have been really hard work without helium or some of the equipment we have now.

BM: Forty-five years almost to the day. Yes, looking back, I guess they were. Bill Gavin and I snuck Uno (Sally Ward Spring) late one night. We took minimal gear, including our “deeperised” Tekna scooters. We used to modify them with a little gas bottle that shot air in through the plate and a Viking exhaust valve, so we could take them deep without them imploding. We knew we didn’t have the right equipment, but you had to get the gear in and out fast. We really needed more stuff, but we couldn’t risk getting caught. So we dropped down and headed off downstream into the flow.

Gavin was in the lead, laying line when we got to a restriction, so we had to leave the scooters. We knew it went—it was virgin tunnel, and we had to have it. So we were both on air at 285-foot swimming balls to the wall. My wetsuit was thin as paper, with the depth. Gavin was ahead swimming like a madman at scooter speeds because that was what the gas plan had allowed for. I got off the line at 285ft in a total silt out. I could almost cut the silt with a knife. I couldn’t see. I couldn’t find the line and I was buzzed out. I swear, If I hadn’t been diving so long, I would have panicked and died.

So I got myself back under control, turned around 180 degrees and inflated, so my tanks were on the ceiling, and I held my sealed beam light to my chest so I could look. I started skip breathing to make my air last, and so I could hear. After about five to six minutes—it felt like forever—I could hear Gavin swimming. Maybe some of his gear was rattling and he swam right past me. I could see the orange glow of his light, so I followed him right on out, and we got back to the scooters, which we were relieved to find, still at 270ft. After that dive, we said all deep dives would be on mix. We were the WKPP. We were the two head guys. We started trying different mixes right after that dive.

HP: Who are the guys you respect? I guess Sheck Exley is a given?

BM: Sheck was a remarkable guy. Even now, I still believe that the world record dive he did in 1989 at Chips Hole, solo, to nearly 11,000 feet and then all the way back out against a raging siphon, is probably a more amazing achievement than Man walking on the moon.

HP: Who else?

BM: I would have to say Jarrod Jablonski and Casey McKinlay. I would never have the balls to do the dives they are doing now. They have really earned my respect. I remember when Jarrod was young and he turned up and we started diving together. We were decompressing on the log at 6m in Devil’s Ear over there, and I wrote on my Wetnotes: “What year were you born?” He wrote me back and I replied that I had been decompressing on that log since he was three years old. Those guys used to just descend on an area and pretty much achieve whatever they wanted. John Zumrick was a very important figure and I don’t feel history has been kind enough to him—a brilliant, brilliant guy.

HP: What are your favourite cave dives in Florida?

BM: Indian Springs. If it’s clear and on a good day and you’re sane, that’ll be your favourite cave dive. Ask people who have dived it when it was like that, it will be 100 times out of 100 people’s favourite. Sullivan is outstanding. Also, Madison Blue through The Rocky Horror and beyond The Courtyard. The water clears, it opens right out, the walls are pure white, and it becomes a stellar cave dive.

HP: How did the Hogarthian equipment configuration come about?

BM: John Zumrick invented the term "Hogarthian". It really started as a joke. I have always been stuck with that middle name, and then Gavin started using the term. We started minimalising—stripping out anything that we did not need. Every time I saw something good—as long as it meshed with the system—I would adopt it. I was one of the first to use the Goodman handle, putting the backup lights under the arms—lots of little things, most of them invented by other people.

HP: What do people fail to understand about diving “Hogarthian” and how does it differ from what people would consider to be a DIR (Doing It Right) equipment configuration?

BM: It is mainly being streamlined—if you don’t need it, don’t take it. I was glad that they changed the name to DIR because there are some differences that I still don’t agree with, like having the wing inflate on the right post. I always have mine on the left, so that if the post rolls off, I'd know, because the inflate stops working. Speed is a big part of the equation for me. I have to limit my dives. I can’t stay in the water for 10 to 15 hours in a wetsuit. Also, sometimes “Chicken Little” comes calling and says, “The sky is falling down,” and you just got to get out of the cave quickly.

HP: If you were going to do a big cave dive like Diepolder, what would your gas strategies be?

BM: I have dived Diepolder a few times. I am a guide there. I have scootered right to the end of the deep 360ft tunnel and swum it as well. I think the last time I did it, I was using something like 13/45. For deco, I prefer 80 percent. I know O2 gives you a slight time advantage, but I find it’s a little easier on the lungs, and in an emergency, it’s 10ft closer to you. I would use a 70ft bottle of 50 percent, as well, on the deeper stuff. People used to criticise Bill Gavin and I for diving air all the time; but back then, there wasn’t anything else, and I still use it for all my shallow dives.

HP: How do you tend to dive stage bottles?

BM: It really depends on the dive and what I am trying to achieve. Whether I am scootering and doing the layout of the cave, there is no fixed way—just what suits the dive.

HP: The deaths of Bill McFayden and Parker Turner in cave diving accidents must have hit everyone hard? A few of you seemed to give up the big exploration dives around that time.

BM: Not for me, but Gavin did. Parker was a wonderful guy. He wasn’t my close friend, but he was a very close friend of Bill Gavin’s. You see, Bill suffered three deaths with Bill McFayden, Parker Turner and Sherwood Schille, and he unfairly got a lot of bad rap for that. There’s a thing that I never went public over with the death of Bill Mc Fayden, and I’ll always feel responsible because I didn’t say no.

Here is what really got him, and I tried to talk him out of it: He insisted on diving this cloth drysuit, on a big, difficult dive. They were awful suits. I couldn’t control one, and this was his first proper dive in this new suit. As I said, I tried to talk him out of the dive, but everyone else told him he’d be okay. Sure enough, he couldn’t control the suit, and he was rushing for the exit, cutting corners, off the line. I considered slashing his suit to try and control him. He was panicking, riding on the back of Gavin’s scooter, but it was too late, and in the end, he shot to the surface and got embolised.

HP: Do you need to lose someone close to you to truly understand the risks of cave diving? Are there dangers of complacency when you’ve been doing it a really long time?

BM: Losing someone sure gets your attention pretty quick. But listen, here’s how it is: When you’ve made thousands and thousands of cave dives, every so often, you’re going to screw up—you’re human. I’ve stepped into water with my air switched off, no inflation, nothing to breathe. Your head only has to be a few inches below the water to drown.

HP: Are rebreathers Hogarthian?

BM: Here’s what I think about rebreathers: They’re a lot of maintenance, and people spend all that money, then they find that every dive they do has to be a stage dive because they need a bailout bottle even just to go to The Dome Room in here (Ginnie Springs). But unlike a normal stage bottle, it doesn’t get any lighter when you are not breathing it, and you can’t drop it.

I reckon there are about 15 people in Florida who actually really need a rebreather: Jarrod and Casey and those WKPP guys and maybe some of the guys, like Brett Hemphill down south, who are diving deep systems like Weeki Wachee, Eagle’s Nest and Diepolders regularly. At least Jarrod’s rebreather doesn’t have electronics, so you don’t have to keep watching it all the time.

I just want to concentrate on the line and what I am doing. If you knew that you could guarantee 100 percent that a CCR (Closed Circuit Rebreather) would not fail, you would be crazy not to have one. You could do any dive you like with it and decompress, but you can’t.

HP: If you asked almost any technical diver in the world, they would know what you meant by Hogarthian or “Hog” rigged. There’s even a dive equipment company named after you now. Did you ever expect the equipment configuration that you guys developed to be so widely adopted, not just by cave divers, but also tech divers the world over?

BM: I never would have guessed it, and I never set out to do it. Just like Gavin and I setting up the WKPP and then Parker Turner coming in and incorporating it, I just happened to be sitting there at the time and got lucky.

HP: You have had plenty of exploration successes and records over the years. In 1988, you broke the world record for a traverse with an 8,500ft dive, from Sullivan to Cheryl Sink up in the Leon Sinks system, and I believe you discovered The Pit in Nohoch Nachich out in Mexico?

BM: The credit for the traverse really must go to Bill Gavin. I wouldn’t have attempted it, but he thought it could be done, and we gave it a try. I physically made the connection. I looked over and there was our other line—a great moment.

Finding The Pit was a complete accident. Mike Madden and I were separated from George (Irvine) and Bill Gavin in a silt-out, and Mike was tying off the line, so I moved over to this room to make him wait and let it clear a little. When I looked down, the floor had just gone from 30ft to 240ft, so I flashed Mike and he shot over like, “Oh [expletive], are we gonna die!” I had only moved over to the room to slow him down and let things clear a little. I was so excited, I had to control my breathing, then he saw it too, and it was like his face was shot with electricity. We shook hands.

HP: Nothing like a new cave, eh? I love Nohoch…

BM: Oh, I tell yah! I wasn’t even meant to be there. I was just in the right place at the right time again.

HP: From your comments earlier, I was surprised to hear that you are still exploring and adding line in well-known systems, like Madison and here at Ginnie Springs.

BM: We added more line in here (Ginnie Springs) only a couple of weeks ago—about 1,500ft beyond the Henkel.

HP: Do you think GUE (Global Underwater Explorers) has done a good job with the legacy of the early WKPP pioneers like yourself, Turner, English and Gavin?

BM: Oh, I think so, and after all, they did some of the biggest dives in the world, at the time.

HP: I gather you’re not a huge George Irvine fan, however?

BM: A lot of things George says, he doesn’t mean. He just says it for reaction and to get into the banter. I don’t bear him any grudge—he’s a very witty guy. He did manage to “turn” on everyone, at one stage or another, and there were a lot of lies. I tried to stay out of it.

Bill Gavin and Lamar English wrote an article on the Deepstop Forum called, “Setting the Record Straight,” to try and redress some of what he said. There is a lot of true history there. Jarrod has always been a good guy. I don’t blame him for getting involved with him. It seemed to me that it was all about money and George had plenty of it. Since he quit, the KPP has made way more progress under Jarrod and Casey than when George was in charge. Some of the things he said when Rob Palmer died were unforgivable.

HP: A diving friend of mine who works for the government back in the UK says there is more politics in diving than there is in politics. It seems particularly bad amongst Florida cave divers. You seem to stay off the Internet and try to keep away from all that.

BM: Oh, it’s terrible. It really is. I do try to stay out of it all. I only had a high school education. I am proud of every “C” I got. I leave the arguing to other people and just go diving.

HP: I always struggle to explain the magic of cave diving to friends—even fellow divers who have never tried it. What do you think?

BM: I still remember the excitement the first time I hit 1,000, 2,000, 3,000ft. I always loved seeing what was around the next corner, and the challenge of getting the equipment right and safely pushing your limits. We move in a medium 800 times denser than air. There is no tougher sport, in my opinion.

HP: What advice would you have for any readers starting out in cave or technical diving?

BM: Keep it simple and streamlined. Just take what you need and nothing more. If you don’t, that’s where your air goes—that’s where your energy goes, right there.

Diving with Bill

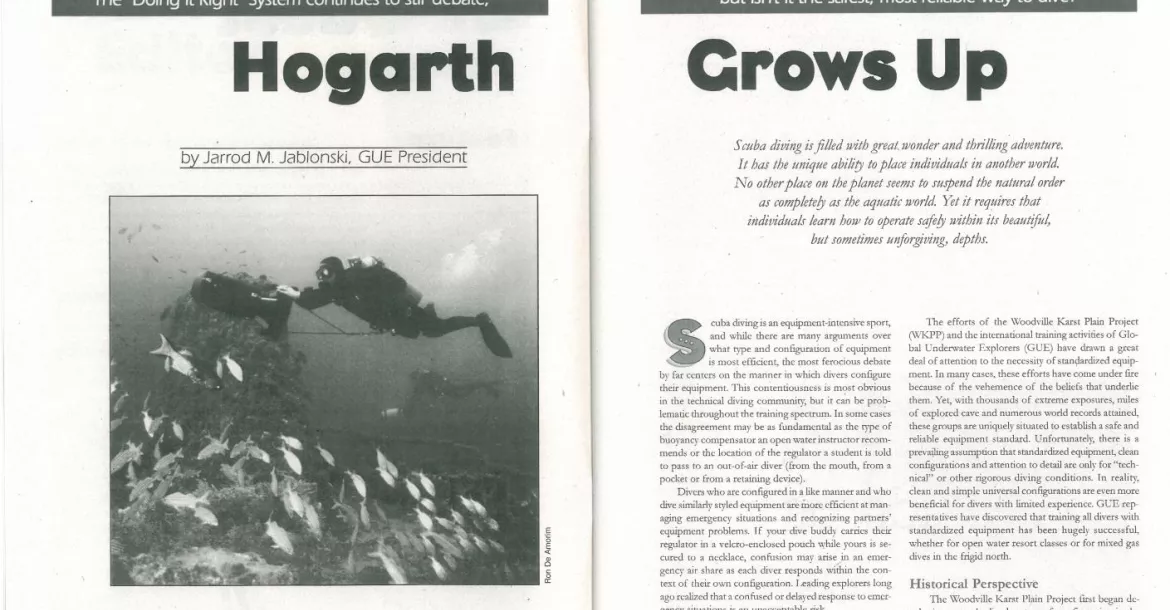

After the interview, Bill and I performed quick bubble checks, having dropped into the water by the Turkey Roost. Then we headed over to the small circular shaft that leads down into the Devils Eye entrance to the system. I was surprised to find that Bill dives a tight, custom-made two-piece wetsuit, instead of the membrane drysuits now used by the vast majority of cave divers. He later explained to me that the wetsuit leaves him a little cold on longer dives, but it is much more streamlined through the water, and the extra speed it gives, compared to a drysuit, is worth the sacrifice.

Bill threaded effortlessly through the series of restrictions that make up The Eye, and we entered The Gallery—the system’s first big room. With myself in second and my dive buddy and photographer, David Martin, bringing up the rear, it becomes evident just how effective Bill’s whole philosophy really is.

I have never been diving with anyone as quick as he is, in the water. Divers with good technique, a third of his age, would struggle to keep up. Bill had already assured us that he had taken things slowly, and I did not doubt he was being true to his word. But with the camera rig in tow, we struggled a little to stay with him.

We shot some stills in The Big Room and then headed for home, finding ourselves back in the entrance to The Eye, around 70 minutes later. I watched Bill decompressing at 3m—motionless, out of the flow, on his favourite spot. He must have spent literally months of his life in this same familiar place, the rock almost bears an imprint of his body.

He switched between his primary and backup regulator on decompression, checking that everything was working fine, feeling for the same familiar, comforting patterns that told him, all is well. Few divers could be more in tune with their equipment. It is almost like it has become a part of him.

For a man who is so closely associated with the birth of the DIR-style of cave and technical diving, with its use of teams of support divers and large reserves of gas and equipment for major exploration projects, Bill’s entire philosophy is the very antithesis of this practice and the undoubted results it can achieve.

From talking to Bill, I came to realise that Hogarthian is truly about one man developing a system to carry out the cave exploration he loves, with the minimum quantity of divers, equipment and gas, and within the tight time frame and budget available to him. Ironically, in this sense, Bill perhaps has more in common with the great UK cave explorers, like Stanton, Short, Mallinson and Volanthen, who tend to dive solo, or in small teams of two.

Bill’s old dive buddy and co-founder of the WKPP, Bill Gavin, used to be something of a philosopher when he wasn’t inventing the DPV Scooter that bore his name. Gavin used to say that great cave divers had “true heart”. He had a red heart with “true” written through it, painted onto the nose cones of all his own scooters. No explanation of Gavin’s eccentric wisdom was ever needed. If you had “true heart”, you just understood what he meant.

As our time together drew to a close, I was struck that Bill, who first set fin in a cave the same month that Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon, still has that passion driving him to find out what is around the next corner. He is still laying line in caves which most people consider fully explored, and still sharing his passion for the sport with other people, so graciously. “True heart” indeed, the phrase may have been invented for him.

The Hog’s Hog Rig

The original Hogarthian Rig is probably the most copied technical diving rig, ever. Bill still uses the original ‘60s US Divers Aqualung Conshelf regulators, which have no poppet to fail, just a simple metal stem going into an orifice. One of them is older than I am. This theme of absolute minimalism carries through everything he uses. And from observing him first hand for a time, the words “fastidious perfectionist” sprung to mind.

The foundation of Bill’s setup is a Dive Rite stainless steel plate, with his signature Oxycheq Razor 50lb wing (ultra-streamlined with only a single bladder—in his words, “made of Rhino hide”). His stage and decompression bottle regulators have no pressure gauges. He has been diving so long that he simply knows how long a bottle will last and believes it removes a significant potential failure point. All the hoses are custom lengths to reduce drag.

For lighting, he uses a Dive Rite 10w HID on a Goodman handle, with simple Princeton Tech backup lights, which he likes because the bulbs are widely available. His main cylinders are the classic US cave diver’s choice of twin 104’s (16.5L each), which are joined with a custom manifold without an isolator. He claims that isolators introduce another potential failure point, and he has never had or even seen a manifold failure in 45 years of diving.

He removes a lot of the risk from this bold decision by over-maintaining his own cylinders and manifold, regularly changing tank neck O-rings and servicing the manifold and valves, which he does himself, along with all his other equipment. The 104s are joined with thick custom bands, which further reduce the chances of any leaks.

Bill’s primary regulator comes off the right post, whilst the wing, backup and SPG (submersible pressure gauge) come off the left. He points out that the original WKPP way to route hoses is with the wing off the left post, so that a roll off kills your inflator and you become aware of it earlier. He strongly prefers this to the DIR “wing off the right post” method. ■

Howard Payne is a PADI Master Scuba Diver Trainer with Dive Wimbledon, a PADI 5-star dive center in London, United Kingdom.