“Crikey,” I thought, “one hundred years ago today that German U-boat was awfully close to the English coast.” I suddenly felt a bit vulnerable. World War I happened right here—just off the peaceful Dorset shore, not in some far-off French trench. A century ago today, I could well be on a sinking ship. Or dead.

Contributed by

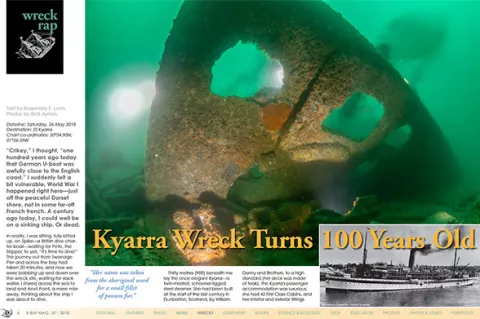

Dateline: Saturday, 26 May 2018

Destination: SS Kyarra

Chart co-ordinates: 50°34,90N; 01°56.59W

In reality, I was sitting, fully kitted up, on Spike—a British dive charter boat—waiting for Pete, the Skipper, to yell, “It's time to dive!” The journey out from Swanage Pier and across the bay had taken 20 minutes, and now we were bobbing up and down over the wreck site, waiting for slack water. I stared across the sea to land and Anvil Point, a mere mile away, thinking about the ship I was about to dive.

Thirty metres (98ft) beneath me lay the once elegant Kyarra—a twin-masted, schooner-rigged steel steamer. She had been built at the start of the last century in Dunbarton, Scotland, by William Denny and Brothers, to a high standard (her deck was made of teak). The Kyarra's passenger accommodation was luxurious; she had 42 First Class Cabins, and her interior and exterior fittings were made from solid brass. She had brass portholes, door handles, navigation lights and name plates. Even the bench end-supports on her deck were made of brass.

“The Kyarra became known as the ship made of brass”

Diver Peter Hayton said: “One of my dive buddies found the most coveted of prizes: the Kyarra name from the bow, in very large brass letters. It took weeks to retrieve them and made the news.”

“Her name was taken from the aboriginal word for a small fillet of possum fur.”

History

The Kyarra was launched on 2 February 1903, and she proved to be a profitable, successful, luxury liner for the Australian United Steam Navigation Company. The 127m (416ft) long ship also had the capacity to transport 7,164 cubic metres (253,000 cubic feet) of general cargo in her fore deck and aft deck holds. She sailed between Fremantle, Western Australia (where she was registered), and Sydney, New South Wales, carrying both fare-paying passengers and cargo.

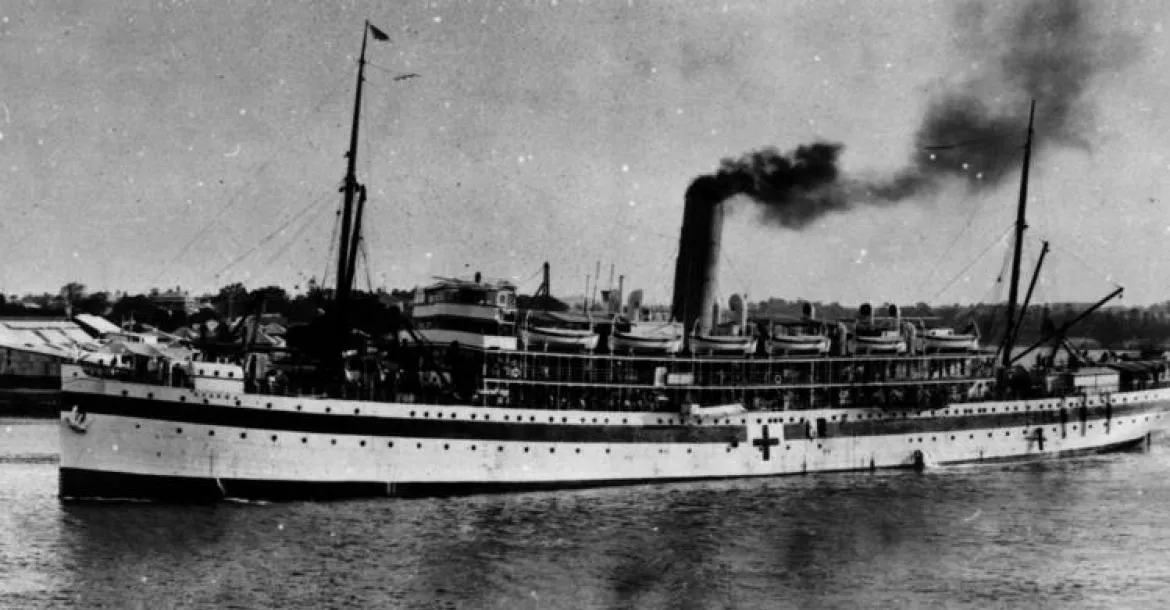

Her life changed on 6 November 1914. Eleven years after she had been launched, the Kyarra was requisitioned and leased in Brisbane by the British Government to be a WWI hospital ship. She became HMAT A55, or “His Majesty's Australian Transports.” HMAT ships were used to transport various Australian Infantry Divisions to their respective overseas destinations. When they were not transporting military, HMAT ships would carry goods to Britain and France.

The Kyarra was painted white, and red crosses were added to her hull to indicate that she was a hospital ship. Her job was to transport Australian medical units to Egypt, and we know she carried a major contingent of Queensland nurses on one voyage.

Five months later, in March 1915, the Kyarra was converted yet again. This time, she served as a troopship and helped land ANZAC expeditionary troops in the Dardanelles. She also saw service in the Gallipoli campaign.

In 1917, the Kyarra became a casualty-clearing ship, and had a 4.7in quick-firing gun mounted on her stern as a defence against U-boats.

On 4 January 1918, the 6,953-ton Kyarra was decommissioned —the Commonwealth control lease had ended. Captain Albert Donovan took command of her on 19 January 1918, and readied the ship for a return to Britain.

In May 1918, the Kyarra was in London. She was fully loaded with general cargo worth GB£1,500 (about GB£100,000 in today's money), which was bound for Australia. Items included bottles of champagne, red wine, stout and vinegar, bales of silk and cloth, French perfume, rolls of lino, sticks of red sealing wax, medical supplies, cigarettes, silver purses, men's big pocket watches and ladies gold wrist-watches. She was also carrying 35 civilian passengers.

Her captain, William Smith, had orders which stated that the Kyarra should sail to Plymouth and embark about 1,000 war-wounded Australian soldiers and repatriate them.

On 24 May 1918, she left Tilbury in Essex and zigzagged down the Channel heading for Devonport, Devon. It was to be her last voyage.

On the morning of Sunday, 26 May, the Kyarra had cleared the Isle of Wight and was moving fast through calm seas around Anvil Point (she could do about 15 knots). Sadly, her captain did not know his course was being tracked by German submarine ace Oberleutnant Johannes Lohs, through the periscope of UB-57.

UB-57

UB-57 was part of the Flanders Flotilla, sailing from Zeebrugge. Her captain had some very good ideas on U-boat warfare and new tactics, and in April 1918 Lohs received the Pour le Mérite. Lohs was having a successful patrol. On 22 May, he had sunk the 423-ton steamer Red Rose, and on the 23 May, he had sunk the P&0 Liner Moldavia (she had been converted into an armed merchant cruiser of some 9,500 tons). Now the Oberleutnant was stalking the Kyarra.

We do know that Lohs torpedoed the Kyarra amidships, on her port side just forward of the boilers. There is, however, differing data regarding the time that she was torpedoed. One reference says 07.20, another 07.40, a third 08.00 and yet another 08.50. It would be reasonably fair to say she was torpedoed somewhere between 07.00 and 09.00.

There are conflicting reports over the fatalities. One states there were nine fatalities. Another states that six men in the boiler room were killed when it was flooded. A third states that five crew were killed in the engine room and an injured man later died at Swanage Cottage Hospital. Yet, another says that one engineer and four firemen were killed in the explosion, and a sixth man died on shore.

I have found evidence of six fatalities. It is possible that five died on board and one in Swanage. I am not making light of these deaths but it could have been so much worse if the Kyarra had been en-route to Australia with the war-wounded.

Again, there are conflicting reports about the attack. One states that a watchman shouted, “Torpedo!” and that it was less than 100 yards away from the Kyarra. Therefore, the order for “hard to port” did not have enough time to be actioned.

Another report says that a torpedo was seen, but the enemy vessel was not. A third report indicates that it was thought the Kyarra had struck a mine, and Captain Smith turned her towards Swanage in a valiant attempt to try and beach her. But it was soon realised that she had been torpedoed.

Either way, the order was given to abandon ship, and the surviving passengers and crew took to the lifeboat.

It is reported that seven to ten minutes later the Kyarra nose-dived beneath the waves. From the time of the attack to her sinking, it took about 20 minutes. It is reported she sank at 09.08, but with four different torpedo times, it is hard to know if this is accurate. Either way, the beautiful ship was gone.

The survivors and passengers, including a pilot, were all landed at Swanage. The W/T code books and confidential papers were sunk by the master.

Location

On 27 May 1918 it was reported that the Kyarra's position was 50°34,30N; 01°56.20W. The Kyarra's mast was showing but not considered dangerous to navigation.

The Kyarra was to lie undiscovered for 48 or 49 years. Again there are conflicting reports that she was found in 1966 and July 1967. At the time of her discovery, it was thought she had sunk closer to St Aldhelms Point. Her position was therefore marked on the chart as a shoal—“a place where a sea, river, or other body of water is shallow”.

First dives on the wreck

She was first dived by two members of Kingston BSAC—husband and wife team, Ron and Linden Blake. Five members of Kingston (Ron Blake, Linden Blake, Adrian Bradley, Bill Foley and Dave Wakeman) and two members of Hounslow BSAC (John Coheagan and Charlie Stoltz) were diving out of Swanage on an inflatable boat looking for the wreck, Carantan. The divers picked up what looked like a wreck on the echo sounder and dived it. Ron and Linden Blake descended first onto an unknown mark and experienced what every wreck diver dreams about—an unknown virgin wreck. She was largely intact—her brass portholes still had glass in them—and she was lying on her starboard side.

The divers formed a company called the Kyarra Salvage Association, to salvage the wreck. In 1974, the propeller was blown off with help from Fort Bovisand. The propeller was to lie on the seabed for two years, before it was subsequently raised by Dave Wakeman, and the funds were paid into the company accounts.

Identification

There are conflicting reports on how the Kyarra was identified. One says that the Blakes “read the brass name on the bow of the ship, which at the time was still intact.” Another report says that the Kyarra was identified by checking all the manifests of the ships sunk off the Dorset coast.

Eventually, a serial number on a stick of sealing wax matched one found in a hold on the wreck. A report also states the Kyarra was identified on 22 May 1966, but I cannot find whether she was indentified because of the wax, the bell or the brass name (and if she was found in 1967, where does the date 22 May 1966 come from?)

We do know that the wreck was positively identified by the ship's name in brass letters from the bow and the recovery of the ship's bronze bell in 1977 by Julian Bamford and (again conflicting names) David Weightman or Dave Taylor. It is reported that the bell is held by Dave Wakeman, so one wonders if Weightman and Wakeman are one and the same person, because the names sound so very similar.

In 1967, Kingston BSAC bought the ship for GB£120, but not the mixed cargo. On 6 May 1969, it was reported that the wheelhouse and the top superstructure had been swept away.

Today, the Kyarra's decaying remains stand 18m (59ft) proud of the rocky seabed, and she is probably the most dived wreck in Dorset. She has been adopted by divers under the Nautical Archaeology Society "Adopt-a-Wreck Scheme," and she is owned by the Kingston and Elmbridge branch of the British Sub Aqua Club.

My dives on Kyarra

As some would say, “this was not my first rodeo,” diving the Kyarra. That occurred on Sunday, 23 August 1992, as part of my PADI Advanced Open Water Course.

I was, frankly, terrified before and during the first part of my “deep dive” on the Kyarra. I calmed down a little when I got half-way down the shot line and was astonished to find the sea was emerald green, as I watched sunbeam shafts dance in the water and lighting up parts of the wreck. The visibility was amazing; I just did not know it at the time, because I had no frame of reference. “So this what wreck diving is all about,” I thought, as I followed my instructor across the deck.

This wreck dive had such a profound effect on me that I was back down in Swanage the following weekend, again diving the Kyarra. My instructor said I was certified to dive to 30 metres, so I decided to put this into practice. This was the first dive I had ever done without an instructor present.

It was my tenth dive ever. Naturally I did it with someone vastly more experienced than I. He had 14 dives. And it was back in the day when octopuses were not mandatory kit. Between us, we had a primary regulator and pressure gauge each, and we shared a watch, a depth gauge and the biggest knife we could lay our hands on.

We got down to the bottom of the shot, and this time, instead of benign sunlight emerald green waters greeting us, there was a current running, and it was a pitch-dark night. Neither of us had a torch. Who knew that English wreck diving could be blacker than a black thing? We clung to each other not knowing what to do next, before moving away from the shot. We promptly lost the safe, fixed line home.

At 15 minutes, we decided it was time to come up. We held each other's arms, Roman handshake style, and started to ascent. We kicked and kicked and kicked and his fins fell off. The next moment, we flumped onto the seabed. I jammed his fins back on. By now, we had done about 25 minutes at 30m (99ft). Our no-decompression time was well and truly blown. We were off the PADI tables.

We started again. Within seconds, we were surrounded by bubbles, thousands of them. Our noses were almost pressed together, and I still could not see his face for the bubbles. I thought his regulator had gone into free-flow. My BCD's over-pressurisation valve gunned loudly, rapidly and repeatedly, and suddenly, we were on the surface. We had made a very fast uncontrolled ascent from seabed to surface in a matter of seconds. To this day, I still do not know why neither of us did not have an embolism or get decompression sickness. We were very, very lucky.

Impact of Kyarra

That dive was forever seared into my soul. Its impact echoed across the years and into my diving career. When I became a PADI Pro, I would always ask myself before I signed a student's certification card off, “Am I signing your death warrant?” I never wanted a student of mine to go through what I went through on the Kyarra.

It took me awhile to venture back and dive the Kyarra again. I dived it in 1996 with Mike Thomas. We had spent the Saturday caving on Mendip, Somerset. On the Sunday, we headed for Swanage. Mike was and is a meticulous diver, but somehow he had left his hood behind and he ended up diving the wreck in a fleece balaclava.

At the turn of this century, I was the Dive Centre Manager at Triton Scuba in Portsmouth. I wanted a benign place to introduce my divers to British sea diving. Swanage beckoned, but not initially the Kyarra.

Although I was taken on the Kyarra as a trainee, I would not consider this wreck a raw-trainee dive. Divers really ought to have something like 20 odd temperate water sea dives under their weight belt before tackling the Kyarra because the visibility, currents and narrow swim-throughs can make this a suitably challenging dive. It is a good wreck for building up depth experience, and it is a great, accessible and entertaining dive for experienced temperate water sea divers, especially if you are nitrox qualified.

“I must have dived the wreck hundreds of times over the years but she is still revealing her secrets. Every dive is different. Exploring the wreck is something I never get tired of."

— Pete Williams, owner of Divers Down and skipper of dive boat Spike

Pete's voice drags me away from my wool-gathering. It is time to dive. It is 09.30, and we are more or less on slack tide. The pool is now open. Exactly 100 years to the day and several minutes after the Kyarra sank, I take a giant stride off Spike and head down the fixed shot line.

After diving the inland quarries over the winter months, the sea temperature is welcoming. It is a balmy 16°C (60°F) on the surface. This promises be a good dive. A hint of the wreck begins to appear. As I fin down the line, the smudgy shadow gets stronger and the outline more defined. Three breaths later, we are over the bow area, and the temperature has dropped to 16°C (53.5°F). I am happy and snug in my O'Three drysuit.

This morning, we have good light and great visibility on the Kyarra. We have no goals for this dive—our mission is to bimble and enjoy the entire experience of the wreck. We cruise over the holds and the obvious swim-throughs, and fin along her plates. Ahead of us are rows of naked window holes, stretching out into the distance. The brass portholes were recovered long ago.

The once-beautiful ship is showing her age, but then she has spent a century at the bottom of the English Channel, being swept by vicious currents. She is still largely intact and recognisable as a ship, although she has evolved into flat-pack wreckage.

Get your eye in and you can start identifying deck fittings from the jumble of metal. Obvious objects include various pairs of bollards, the mast, a large winch and a boiler, complete with a resident curious conger eel (Kyarra had four boilers). Some objects are less obvious—random bits of the engine mechanism, a capstan and the propeller shaft.

Memorial

A pair of divers pass us, mission-focused, heading for the boiler. Today, Divers Down (the oldest dive school in the United Kingdom) has teamed up with the Isle of Purbeck Sub Aqua Club (IPSAC) to lay a wreath on the wreck. Nick Reed (Training Officer) and Chris Dunkerly (Chairman) of IPSAC will place the wreath to commemorate the six men killed a century ago today.

Pat Collins, co-owner of Divers Down and secretary to the Friends of Swanage Pier, said: “The Kyarra is one of the most iconic wrecks on the south coast. Divers use our boats to visit the wreck throughout the summer and we felt it was important to mark the 100th anniversary of her sinking by remembering the six men who died on that May morning in 1918. The Kyarra can only be dived at certain states of the tides due to the fast currents so we are lucky that we will be able to dive the wreck within an hour of the actual sinking time.

"The commemoration is even more special as this year we celebrate 60 years of Divers Down. Our friends in the Isle of Purbeck Sub Aqua Club are also celebrating forty years since the founding of their branch of the British Sub Aqua Club.”

Parting thoughts

As we mooched over broken beams and deck plates, our torch beams picked up a school of bib. Their silver bodies look as though they are fresh from a BBQ grill. Strong black stripes run horizontally down each fish, as though their scales have been seared over hot coals.

If you care to look, there is quite a lot of life on the Kyarra. Patches of vibrant jewel anemones and hydroids coat the structure. Interspersed, are odd clumps of light bulb sea squirts, cup corals, sandalled anemones and deadmen's fingers.

We have almost made it to the rudder as the current in perceptively begins to pick up. The Kyarra is a very tidal wreck and you can only get on her twice a day. It is almost time to head to the surface. A cheeky tompot blenny is in full-on cute mode, as we head amidships to find a quiet area to deploy our delayed surface marker buoys.

As I sit on my safety stop in the brisk current, I wonder when I will next dive the Kyarra. It seems I have visited her at key times in my diving career. Each of my dives has been unique on this big wreck—each dive different. And the more I explore her maritime history, the more I am beguiled by her. I surfaced with more questions about her sinking, wanting conclusive accurate answers. ■