Returning from the pristine reefs of Tobago, I flew over the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. Aghast, I set out on a journey that would help me illuminate waters of the United States to help people better understand their national treasure. I became the first woman to dive all 50 states at the end of last year.

Contributed by

Factfile

Jennifer Idol is the first woman to dive 50 states and author of An American Immersion. She’s earned more than 26 certifications and has been diving for 20 years. Her underwater photographs and articles are widely published. A native Texan, she creates design and photography for her company, The Underwater Designer. Visit uwDesigner.com to see more of her work.

REFERENCES:

Hurricane and tropical cyclones. Weather Underground. http://www.wunderground.com/hurricane/damage.asp?MR=1.

How much water is on Earth? U.S. Geological Survey. July 24, 2015. http://water.usgs.gov/edu/gallery/global-water-volume.html.

Restoring the Gulf Beyond the Shore. Ocean Conservancy. Page 1. http://www.oceanconservancy.org/places/gulf-of-mexico/restoring-the-gulf-beyond-the.pdf.

Martinez, Andrew J. Marine Life of the North Atlantic. Aqua Quest Publications. 2010. Third edition. Page 162.

When I set out on my journey, I was already an experienced local diver that appreciated the diversity of my Texas diving. As an underwater photographer, I thought people would learn to value and protect their waters if I created compelling imagery. Despite my experience, I didn’t know what I would see and experience on my journey. In the United States, I had only previously dived Texas and Florida.

I did expect to see a lot of green water filled with rocks, but suspected I would discover much more. Though I found my share of sand and rocks, I encountered beautiful and strange life all across the country on a quest that would become a great American adventure.

The first states I visited were both beautiful and sobering. From the shores of Florida and Louisiana, I was reminded of my purpose at the outset. I saw workers collecting oil remnants from the beach where I dived. They were protected by masks, gloves, hats and even booties, while my buddies and I wore only swimsuits and wetsuits as we prepared to enter the water from which they protected themselves.

Shortly thereafter, I dived on oil rigs within a couple miles of the very site of destruction I witnessed. Underneath, sea life dominated the rig structures. Tropical fish swam circles around the structures, so full with Tubastrea sun corals that the metal structure was obscured beyond recognition. Louisiana waters are not an empty place for us to mistakenly introduce harmful chemicals. According to the Ocean Conservancy, more than 15,000 species inhabit the Gulf of Mexico.

I marveled at odd findings in Alabama at the stern of a Navy tug. Leopard toadfish and polka-dot batfish scowled at me from the sand. These small fish rely on camouflage as they hunt for food. On my ascent, I observed schools of red snapper swimming through the wreck.

Between dives, I experienced my first encounter with wild bottlenose dolphins. Their curiosity and intelligence were readily apparent as they herded me away from the fish they were trying to catch. This remarkable beginning influenced my five-year journey as I transformed from an underwater photographer into a conservation artist dedicated to our local waters.

Truly diverse

Water only covers seven percent of the United States, including groundwater and frozen water, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS). Therefore, much of my journey was spent driving across vast landscapes.

I observed the transformation in our country from wetlands, mountains and plains to tundra and purposely sought to reveal this diversity. I explored 2,500 feet (762m) into caves, dived in oceans, visited quarries, sought out ice diving and explored wrecks. I wanted to showcase unique underwater landscapes like the tannic water mixing with fresh water in Ginnie Springs.

Our national parks protect the greatest of our American landscapes. In Yellowstone Lake, I explored geothermic formations. Yellowstone National Park is a land of extremes, from 459ºF (237ºC) in springs that host thermophilic bacteria to 40ºF(4ºC) where bass live.

I witnessed the effects of natural events on the history of Glacier National Park. Uprooted trees likely slid into Lake McDonald near Sprague Creek during an historic mudslide, just as the trees found in Jenny Lake in Grand Teton National Park and in Fallen Leaf Lake in California. Historic tools lay at the bottom of the head of Lake McDonald, reminders of human activity during park construction 100 years ago.

Greatest sites of the journey

Traveling across 3,805,927 square miles (9,857,306 sq km) is no small feat. Simply covering the distance in itself could be great. I drove more than 72,000 miles (115,872km) and took 80 flights to complete the quest. North Dakota would be the longest of the trips at nearly 3,800 miles (6,116km).

This challenging and quantifiable goal was defined by rich experiences. The richest of these included the warmest dive in Utah and the coldest in New Jersey and Ohio. While it snowed outside, I enjoyed 93ºF (34ºC) waters in Homestead Crater. Open Water students learned to dive in comfortable blue water.

The water bubbles through small vents in the bottom of the cavern and is kept warm all year-round by geothermic activity. The first divers in the crater lowered themselves through the hole in the ceiling, but an easily accessible entrance has since been created in the side of the dome. I dived the crater in February wearing only a swimsuit, with two feet (0.6m) of snow accumulating during my dive. Calcite particles filled the water, making it too appear snowy but very blue.

My first and coldest dive on the Stolt Dagali wreck in New Jersey taught me to wear sufficient thermal protection for my hands. Having the right equipment makes these dives enjoyable. I later purchased dry gloves to help even more. Swimming through this Norwegian tanker felt like floating through history, from when it sank in 1964 to the more recent history of divers who make this a destination.

Snow and ice were foreign to me at the start of my journey. As a Texan, I had little experience with either, so naturally sought out an ice diving certification. Ice diving in Ohio was also the coldest of my American diving experiences at 38ºF (3ºC), more so than even Alaska. It was such a fun experience that I also sought ice diving in Minnesota. This unique overhead environment is unlike any other kind of diving. I used sealed regulators so they would not free flow from freezing and dived with a sidemount configuration for redundancy.

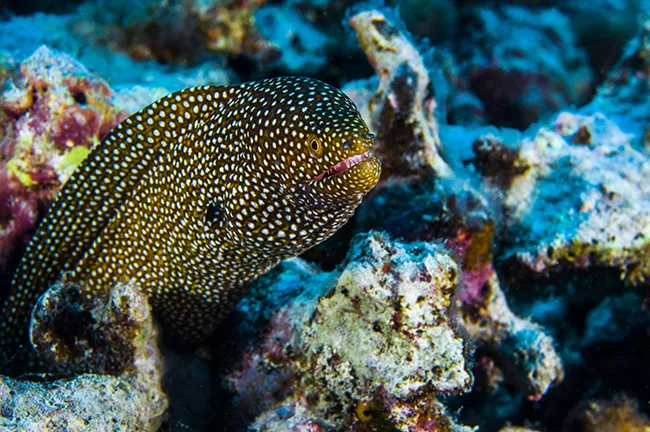

So much of my experiences across the country was filled with surprises. Though I researched the logistics for the dive sites, I did not know what creatures I would see or what the conditions would be like. I was often surprised by seeing animals that local divers thought were normal and abundant, but to me were remarkable and odd. Garibaldi and opalescent nudibranchs thrilled me on Catalina Island in California. In Hawaii, I learned about thornback cowfish and whitemouth moray eels.

The most surprising locations were Puget Sound in Washington and Beavertail State Park in Rhode Island. Life in the north is unexpectedly prolific and large. In Seattle, giant plumose anemones seem to sprout from every hold they can find footing. While the water was green, the water became clearer after the first 20 feet (6m). In Rhode Island, I hoped to see a horseshoe crab. Not only did I get to see many of these living fossils, but I saw them in pairs as part of their mating process. Despite appearances, they are not actually crustaceans. Instead, they are more closely related to arachnids.

I saw the strangest fish in Tennessee—a paddlefish. My buddy, Ben Castro, and I explored the Loch Low-Minn quarry where these fish lived. Paddlefish are a prehistoric filter feeder, little changed from their fossilized ancestors. I observed paddlefish each maintaining their own personal space and turning away when encountering another. In this dive site stocked with attractions, we also explored plaster sharks, buoyancy courses, and a statue of David.

Before I set out on this adventure, I wanted to define myself as a wreck diver. On this quest, I dived 21 notable wrecks, including the world’s largest wreck sunk to create an artificial reef, the USS Oriskany, at 888 feet (271m) in length. This dive to 220 feet (67m) was also my deepest dive of the journey. Though sunk in 2006, I saw only urchins, sea cucumbers and thorny oysters growing on the outside.

In the northeast, I visited the USS Arthur W. Radford, 529 feet (161m) in length. This wreck was smothered by clams and decorated by anemones. So notable were the wrecks, that my 50th state featured wrecks of the Great Lakes. I explored the William Young, Cedarville and Eber Ward in Michigan. Most of the wrecks I visited were steel hull, but in the Great Lakes, I saw wooden ships preserved in the fresh water.

The greatest destination in my quest is hard to identify because each of the outstanding destinations was so different from the next. From the remarkable historic diving equipment shared by the Northeast Diving Equipment Group (NEDEG) to America’s last great wilderness in Alaska, it is nearly impossible to decide which is best.

I dived Alaska, the 49th state to become part of the United States, for my 49th state. There, I admired lion’s mane jellyfish and fulfilled a dream to see salmon during their spawning season. These remarkable fish have been immortalized through stories of their reproductive journey. Unexpectedly, I also saw harbor seals, Steller sea lions, puffins and sea otters. On a tour, I visited a glacier and waited while I watched it calve into the ocean. Standing near this activity, I felt nature’s vastness.

Facing challenges

From hurricanes to limited visibility, nature challenged me every step of the journey. I rescheduled my trip to the U-352 due to Hurricane Irene, which made landfall in North Carolina the week of my trip and is cited by Weather Underground as the seventh-costliest hurricane in United States history. I detoured to Lake Mead in Nevada.

Another weather-driven detour, I was unable to dive my planned site in Lake Michigan due to extraordinary waves. I instead dived the deepest inland lake in Wisconsin, Lake Wazee. I brought a group of Texans on this dive, so we made the most of our trip and also visited the U-505 in Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry. We read in Shadow Divers by Robert Kurson that John Chatterton visited this U-boat, and also we were planning to dive the U-352. Having never seen a U-boat, this seemed a good way to familiarize ourselves with the wreck.

Limited time and financial resources constrained each of the trips. I visited 106 dive sites in five years. My photography was often limited to one or two dives set between days of travel. Yet, I succeeded in completing the quest and was enriched by all that I saw.

By the fourth year of my journey, I became tired from the work to create the best images in too few dives. At this time, I scheduled my next dive in Portland, where I was amazed at the clearest water of my quest in Little Crater Lake. The tall pine trees around and in the water beautifully decorated this spring-fed lake at the top of a mountain.

The Pacific Crest Trail intersects with this dive site. I observed hikers beginning their journey on this 2,663 mile (4,286km) long quest from British Columbia to the border of Mexico. They reminded me of when I set out on my quest to dive the 50 states. I left inspired by this dive and full of the sense of wonder I hoped to bring others.

Gatekeepers to the underwater world

Divers are stewards of local dive sites because we are experts of what lives underwater. We see a world hidden from most people. Without sharing our stories, others might not know to value these places.

Fortunately, divers across the country are eager to share local sites. This helped me dive with more than 74 buddies. Local divers across the country enriched my knowledge of American diving, helping me find the most notable areas of each site.

Detailed information about sites was surprisingly sparse. While I could find a site, it took research to determine when I could dive and by what rules I needed to follow. I now carry a dive flag to shore dives because this is the most common requirement. Now that I know what can be experienced, there are a number of sites I would like to return to.

Sharing the story

For me to be a steward of the greatest diving in the United States, I share the story through my photography, articles, and my book An American Immersion. To be released in March, my book showcases the photography and gives insight into how an oil spill inspired me to undertake this quest.

Through the story, I hope to inspire people to love and care for our waters across the country. Our natural resources are a treasure to protect. I intersperse big topics like invasive species, runoff from fertilizers into lakes and overfishing throughout the journey. Unfortunately, I encountered all these in my journey, especially the zebra and quagga mussels that overtake our fresh water.

Five years of change

In the course of five years, more changed than my perspective on diving in America. A number of dive sites and stores I visited closed or changed ownership. Maine Divers Scuba Center took me to see the American lobsters crawling in the bay in Portland, Maine. They have since closed their store and operate seasonally as a charter.

I was fortunate to see bluegill sunfish nesting in Lake Rawlings in Virginia. While the Blackhawk helicopter is the premiere attraction, I was excited by these colorful fish exhibiting their reproductive behavior. This too changed hands, and Lake Rawlings closed, reopening as Lake Phoenix.

Other businesses like Pennyroyal Scuba Center Blue Springs Resort expanded. Sites change in other ways, such as with Santa Rosa’s Blue Hole in New Mexico. The sculptures I photographed were taken from this site, but wonderful changes are also taking place. The ADM Exploration Foundation helped restore the spring to its original state.

Unusual in Utah, tropical fish inhabit Bonneville Seabase, where I saw two nurse sharks that have since died at 25 years of age. I revisit many of the dive sites, but each trip is a moment in its history. How we see the underwater world is like a still photo in a motion picture.

I am encouraged by the bigger story through the work of scientists like Dr Donna Shaver on North Padre Island. She has spent more than 30 years studying the endangered Kemp’s Ridley turtles and successfully managed a hatchling program that is rebuilding their population in Texas. More opportunities like these abound for us to be stewards for our local waters.

The next adventure

Diving all 50 states exceeded my expectations. As I traveled across the country, I filled my dive list with dozens of new places I would like to dive but could not visit during this quest. When I share these moments in presentations at dive shows and events, I hope to inspire you to undertake your next diving adventure. I also plan to continue finding places full of the surprise and wonder I found in American waters. ■

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #71

- Läs mer om X-Ray Mag #71

- Log in to post comments