Like the tips of icebergs, the islands of the Azores archipelago are just the visible peaks of a remarkable chain of underwater mountains that rank among some of the highest in the world. Those mountains rise up from the Azores Platform, a huge area of nearly 6 million km², which in itself is just a small part of the amazing Mid-Atlantic Ridge that runs the complete length of the Atlantic Ocean—from the far north and the Arctic Ocean, to the deep south and the Southern Ocean.

Contributed by

Factfile

Don Silcock is the Asia Correspondent for X-Ray Mag, based in Bali, Indonesia.

For extensive location guides, articles and images on some of the best diving locations in the Indo-Pacific region, please visit his website at: Indopacificimages.com.

The Azores Platform is some 2,000m below the ocean surface, but the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is grounded on to the seabed another 2,000m below that, while the tip of Pico (the tallest island of the archipelago) is 2,350m above sea level, making the mountain that is Pico about 6,500m high in total elevation. Sat as they are, roughly halfway between the edge of southern Europe and the tip of North America, the nine islands of the oceanic archipelago offer the only shelter from the notorious seas of the North East Atlantic. Underwater, that archipelago sustains an incredible ecosystem because those nine visible peaks are just a fraction of the 100+ underwater mountains and seamounts that are both a beacon to marine life and a catalyst for the interaction between the many pelagic species that aggregate there.

Location, location, location…

Situated at the junction of the North American, Eurasian and African tectonic plates, the Azores Platform and its underwater mountains were created by intense seismic and volcanic subductive interaction between those plates. Swept by the warm tendrils of the southern Gulf Stream, rich in tropical nutrients and dissolved organic nitrogen, the archipelago is far enough south from the frigid winter waters of the Arctic that even in midwinter, the area can support the food webs necessary to sustain a complete marine ecosystem.

So, while the rest of the North Atlantic is practically barren at that time of the year, the Gulf Stream creates rich upwellings around the mountains and seamounts of the Azores that become fertile oases to which the large pelagic animals of the region aggregate. Come spring and rising temperatures, the Azorean waters burst into life with huge planktonic blooms and krill spawning events that create the perfect feeding conditions for the hungry great whales of the northern hemisphere, which are migrating north to their Arctic summer feeding grounds.

Great whales

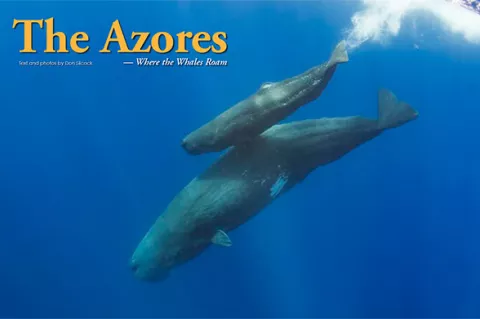

The deep waters, undersea mountains and overall ecosystem of the Azores make it an almost perfect location for sperm whales—deep-diving animals that hunt and feed on the giant squid that abound in the depths around the archipelago. It is also one of the few places in the world where, under a special permit from the Regional Environment Directorate, it is possible to be in the water with the sperm whales; and in September 2016, I made the marathon journey from Sydney to do just that.

September is the optimum month to experience the Azores underwater as the onset of autumn brings the best visibility, the water temperature is still reasonable and most of the tourists have departed. It is also the end of the main calving season (which starts in July) and this means there is the highest chance of encounters with curious juvenile sperm whales.

I was based in Madalena, the pleasant main town of the incredibly picturesque island of Pico in the central area of the Azores, which is dominated by its volcano, Mount Pico—the highest point in the archipelago and in all of Portugal. Mount Pico was thankfully dormant during my visit, having been so since its last eruption in 1718, but a drive up to the flanks of the volcano on a clear day affords a view that seems to stretch to eternity and puts into perspective the isolation of these incredible islands, far out in the North Atlantic.

It is that very view, combined with the nature and tenacity of the Azorean people, which allowed a shore-based sperm whaling industry to succeed, because from up on high, it is possible for an experienced whale-spotter to not only see the “blow” of a whale at the surface up to 50km out at sea, but also tell what type of whale it is. The whale look-outs are called “vigias”, and they are distributed around the islands of the Azores at strategic locations to provide virtually complete panoramic coverage of the waters. Somewhat ironically, the same methodology is used to this day to spot the whales and guide the whale-watching boats to them—although mobile phones have long replaced the elaborate small rocket firing and white sheet signaling that were originally used.

But it is not just sperm whales that frequent the archipelago. At various times of the year, the other great whales can be seen with the leviathans of the ocean—the blue whale—appearing in March, and followed by fin, sei and humpback whales. The rich waters of the Azores are also one of the best places to see blue sharks, pilot whales, false killer whales, mobula rays and multiple species of dolphins.

Whaling history

The people of the Azores are known for their quiet, peaceful but industrious nature, and it was those characteristics that struck the captains of the American whaling ships that visited the islands at the end of the 18th century. The American ships of that time were in many ways the precursors of the infamous “factory ships” of the early 20th century, which so devastated the global whale population. They were highly evolved vessels that could catch whales, using small open boats launched from the main ship, and then process the whale carcasses using an on-board brick furnace called a try-works to boil the blubber.

Designed to pursue the deep-water whales out in the open ocean, they specifically targeted the sperm whale because of its highly-prized oil, which was lighter and purer than that of other whales. Plus, the high-quality ivory teeth of the sperm whales were used to make decorative objects and their intestines sometimes contained ambergris, which was valuable as a fixative in perfumes. But most prized was the spermaceti wax-like liquid in the whale's head, which was used to make what we would now call “designer candles”, which were in great demand among the wealthy class of the time because of the clear, brilliant light they gave off when burned.

Many Azorean men signed on with the American ships, quickly earning strong reputations as good “whalemen” who excelled as lookouts, boatmen and harpooners; plus, they did not complain about the low pay, poor conditions and extended trips that often stretched out to two to three years at sea. In the second half of the 19th century, when the American whaling industry went into steady decline, the Azorean whalemen brought their acquired skills home and established land-based whaling in their own islands, with the first known whalery being built on the island of Faial in the 1850s.

By the early 1900s, Azorean whaling was well established, and at its peak in the 1940s and early 1950s, there were a total of 21 stations in operation across the nine islands of the archipelago. At one point, 40 percent of the world’s take of sperm whales was from the Azores.

In a remarkable piece of living history, the techniques of the American whalers—fashioned and honed as they were in the early 18th century to hunt, harpoon and kill sperm whales from open boats—were in use in the Azores through to the end of whaling there in the mid-1980s. The only concessions to modern technology the Azorean whalers made was the introduction of motor tow boats in the early 1900s, so that the open boats used for the hunt could get to the whales much quicker—but the hunt itself was conducted by oar power. Secondly, radio telephones were introduced in the 1940s to allow direct communication between the whale boats and the spotter up in their cliff-side vigias.

I must admit that I had virtually no knowledge of either the Azores or the local whaling industry before I went there—basically, I went for the sperm whales, figuring that (as normally happens on my travels) the experience would make me realize what I did not know. Many things left a strong overall impression upon me from this trip, but probably the most indelible were the people and culture of the Azores, together with just how hard it can be to get close to and photograph sperm whales.

People and culture

The islands of the Azores are a long way from everywhere, and although discovered in the 14th century, it was nearly a century later before the first settlers arrived—bringing with them everything they needed to survive, while they built houses and cleared land to plant the crops that would sustain them. Life was tough, which is most probably why the men who signed onto the American whaling ships did not complain much. That toughness and resilience was the first thing that struck me about the people of the Azores. No matter how repelling whaling is, the basic fact that their men took to the open seas in small boats to catch and kill by hand such huge creatures is quite an amazing story.

I did a lot of reading and research with “Dr Google,” as I wrote this article and stumbled on two significant pieces of information in the process. The first was a Discovery Report by British marine biologist Dr Robert Clarke, who spent 10 weeks in the summer of 1949 assessing the sperm whaling industry in the Azores. His excellent report "Open Boat Whaling in the Azores" makes fascinating, but somewhat harrowing, reading and puts the whole thing into a clear historical perspective.

Then, there is the short film made in 1969 by William Neufeld called "The Last Whalers", which is available on Vimeo. Although dated in format, it provides an overall vignette into whaling in the Azores that was both horrific and heroic. I have always viewed whaling as a greedy and evil thing. I still do, but seeing it from the perspective of the Azoreans, who were basically doing what they had to do in the only non-agricultural industry there was at that time, allowed me to personally come to terms with what happened to the sperm whales of the Azores.

Overlay on that the many religious festivals, patron saint and traditional holidays that are integral to the archipelago, the islander’s way of keeping their culture strong and alive while offering thanks to their gods, and it is easy to understand why the Azores are indeed a very special place.

How many sperm whales are there?

The total number of sperm whales globally is not known, but the most commonly used estimate is 360,000—a number extrapolated in 2002 by Hal Whitehead, Professor of Biology at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, using an innovative mathematical model and a variety of existing data.¹

He also estimated that the number of sperm whales before hunting began was probably about 1.1m, and early open-boat whaling had reduced that number by some 29 percent by 1880 to around 780,000 animals. From then on, there was a slight but slow recovery through to the end of WWII and the introduction of industrial-scale hunting, which completely devastated the global population of sperm whales, reducing it to the estimated 360,000—32 percent of its original number!

Whitehead also attempted to estimate the possible rate of recovery for the global sperm whale population and concluded that one percent per year was the maximum possible, which if correct, would mean that in 2016, there were just under 420,000 whales—38 percent of that original estimated population. The general scientific consensus seems to be that a one percent increase per year is overly optimistic, because it does not—and cannot possibly—take into account the ratio of male and female whales taken by the whalers and the inevitable impact that this would have on the social and reproductive behavior of the global population.

So, the best guess seems to be in the region of 380,000 to 400,000 sperm whales alive today, and explains why they are still classified as “Vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Photographing sperm whales

The total number of sperm whales in and around the Azores archipelago is also not known, but from the results of various surveys that have been conducted, and referencing that data back to the seminal work of Dr Clarke, it seems that a reasonable estimate is about 2,500. That number includes the small, but unknown, number of whales that are year-round residents and those that are known to migrate between the Azores and other areas of the North Atlantic, with most males going north in the winter months while the mothers and their calves head south.

Put in very simple terms, the total area of the Azores is just under 2,400km², so if there really are 2,500 whales, that would be roughly one per km²—but sperm whales are very gregarious animals, and females usually gather with their calves in social groups, typically with one or two males. Then, allowing for the fact that sperm whales socialize at the surface for about 25 percent of their time, and the other 75 percent is spent foraging in the depths for food—you quickly get the picture that when a group is encountered, the chances of spending much time with them is limited, to say the least. Add to that the fact that whaling ended in the Azores less than 30 years ago, plus the average age of a sperm whale is believed to be at least 50 years, and you can understand their reluctance to linger at the surface when they hear boat engines approaching.

So, while we had many encounters with the sperm whales of the Azores, there was virtually no close interaction or intimate moments of connectivity with them, as they typically would move away at best, or dive as we got close—meaning we were limited to drive-by photography most of the time.

Other big animal encounters

The really great thing about being out on the open waters around the island of Pico and neighboring Faial in the search for sperm whales is the fact that you are just a phone call away from other big animal encounters, because of the spotters high up in their vigias. The same technique they used back in the whaling days is used to spot and identify the large mammals as they surface to breathe.

One day, when we were out to the far northwest of Faial, looking for a group of sperm whales that had been spotted earlier, a call came through that there were three pods of false killer whales to the southeast of the island. Cameras were quickly secured, and we took off at full speed in the RIB, which normally carries a full load of whale watchers instead of four whale swimming photographers—fast! Within 40 minutes, we were dropped into the water with the first pod, which was below us in the blue hunting tuna at an incredible pace.

No Kodak moments were forthcoming, so we got back on the boat and tried the second pod, quickly coming face-to-face with a pretty aggressive false killer whale that proceeded to charge me several times and then ominously circled one of the other swimmers. They were a tense and quite exciting few minutes, but the false killer apparently decided against any further moves towards us and returned to the tuna hunt. Similarly, on another day, we were just north of Pico and the call came through that there was a pod of pilot whales about 10km south of our current position. We were able to get in the water with them within minutes.

Princess Alice

This large submerged seamount is probably the most famous dive in the whole of the Azorean archipelago because of its remote location, depth, challenging conditions and the potential encounters that can happen there. The area was discovered in 1896 during an exploration of the Azorean archipelago led by Prince Albert I of Monaco aboard his research yacht Princess Alice, which was named after his American wife Marie Alice Heine.

Prince Albert I, an accomplished oceanographer and explorer, named the area Princess Alice Bank. What makes the location special from the many other underwater mountains and seamounts of the Azores is that its tip is just 35m below the surface, so it is possible to dive it—just so. It is a large area of about 100km², but the shallow seamount is located just over 90km southwest of Pico Island, which means a journey of around three hours each way, in the open ocean.

So, good conditions are required to make the trip, and by the time you get back to Pico in the late afternoon, your thoughts may well be concentrated on arranging an appointment with the local chiropractor.

It is an adventurous dive, to say the least. As the boats anchor onto the tip of the seamount, the only way to safely do it is to use the anchor line for both the descent and ascent, because if you let go, the strong currents and upwellings that swirl around the seamount can sweep you off into the blue. A typical dive will allow you to spend a few minutes exploring the area around the peak of the seamount at depths of at least 40m and the surrounding deep blue water, together with the sloping sides of the seamount, hints at the extreme depths around you. The rest of the dive is spent on the anchor line, as you slowly ascend, but this is where the show usually happens, when the open water pelagics come and strut their stuff—manta and mobula rays are commonly sighted, but many other large creatures like tuna, barracuda and marlins often put in an appearance.

Blue sharks

No visit to the Azores would really be complete without experiencing the blue sharks that frequent the deep waters around the islands. Large, slender-bodied pelagic animals, mature blue sharks grow to about 3.5m in length and are found in multiple locations across the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans and are known to go as deep as 600m below the surface.

In the Azores, they are enticed up from the depths to the northeast of the islands of Pico and Faial using chumming techniques, which allows divers to be in the water with them near the surface and makes for some great photo opportunities. Their size, intense curiosity and apparently fearless nature makes for some interesting and very close encounters, plus the fact that it all takes place in open blue water makes the overall experience quite something!

A personal summary

It is a really long way from where I live to the Azores—involving five flights and almost two days of travel. I did it because I really wanted to experience the sperm whales in the water, and I did just that, but it was not really the intimate experience I was hoping for.

However, over the three weeks I was there, I developed a deep interest in the islands, the people and their culture, and particularly the creatures that come to the deep waters of the archipelago. The more I read and researched this article, the more intrigued I became with the Azores and the more determined I am to go back to those special islands in the remote North Atlantic! ◼︎

REFERENCES:

¹ Whitehead, H. 2002. Estimates of the current global population size and historical trajectory for sperm whales. Marine Ecology Progress Series, Vol. 242.

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #80

- Läs mer om X-Ray Mag #80

- Log in to post comments