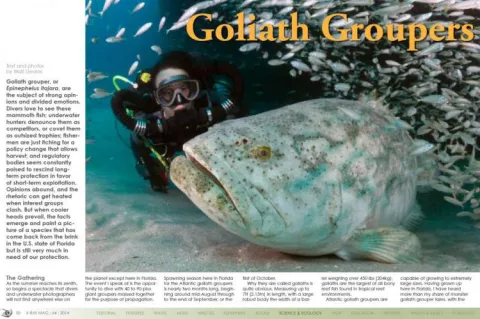

Goliath grouper, or Epinephelus itajara, are the subject of strong opinions and divided emotions. Divers love to see these mammoth fish; underwater hunters denounce them as competitors, or covet them as outsized trophies; fishermen are just itching for a policy change that allows harvest; and regulatory bodies seem constantly poised to rescind long-term protection in favor of short-term exploitation.

Contributed by

Opinions abound, and the rhetoric can get heated when interest groups clash. But when cooler heads prevail, the facts emerge and paint a picture of a species that has come back from the brink in the U.S. state of Florida but is still very much in need of our protection.

The Gathering

As the summer reaches its zenith, so begins a spectacle that divers and underwater photographers will not find anywhere else on the planet except here in Florida. The event I speak of is the opportunity to dive with 40 to 90 plus giant groupers massed together for the purpose of propagation. Spawning season here in Florida for the Atlantic goliath groupers is nearly two months long, beginning around mid-August through to the end of September, or the first of October.

Why they are called goliaths is quite obvious. Measuring up to 7ft (2.13m) in length, with a large robust body the width of a barrel weighing over 450 lbs (204kg), goliaths are the largest of all bony reef fish found in tropical reef environments. Atlantic goliath groupers are capable of growing to extremely large sizes. Having grown up here in Florida, I have heard more than my share of monster goliath grouper tales, with the behemoths weighing in excess of 1,000 lbs (454kg). Yet, I have never met one this big. Nor have I seen one as large as the 680-pound (308kg) IGFA (International Gamefish Association) all tackle record grouper that was caught by sportfisherman off Fernandina Beach, Florida, back in 1961.

However, when you come face-to-face with one even half the size of that IGFA fish underwater for the first time, it will be an encounter you will never forget.

Throw in the magnification factor created by water’s effect on a diver’s facemask, the perspective to just how big that fish is, can be amplified enough to make a 6ft (2m) long brute with a girth equal in diameter to an oil drum appear as big as a compact car.

Where and when

The most favorable location for encountering these giants happens between two natural and four artificial reef sites along Florida’s Palm Beach County Coast. From mid August to the end of September/early October, these six key sites play host to the only goliath grouper spawning aggregations known to take place off Florida’s east coast. Interesting, in that all of these take place less than five miles from shore. Where as the rest (approximately seven in all) take place in the southern Gulf of Mexico, 25 to 40 miles offshore of Florida’s west coast.

For underwater photographers on Florida’s east coast, the timing and length of these huge spawning aggregations, combine with often highly favorable conditions like underwater clarity in the 60 to 90ft (18-27m) range, tropical water temperatures and calm seas, make it easy for them to capture images that defy words. In comparison to most other grouper species, this romance period these fish follow is more like a marathon than a 50-meter dash. While these concentrated annual gatherings don’t really get going till mid-August, the journey for some actually begins as early as mid-July. More recent studies have found, following tagged fish, some of the distances traveled to reach one specific spawning aggregation site have been recorded greater than 300 miles (483km).

Spawning

Having followed these fish since the first spawning aggregation reappeared after a three-decade-long hiatus on a local site off Jupiter called the Hole-in-the-Wall back in 2001, I can pretty well describe the process by which it typically takes place.

Around the timing of the first full moon of August, the bulk of the spawning fish have completed their journey, swelling the ranks on a single aggregation site from a dozen big behemoths to a herd topping 40 to 60 fish. Typically the first to see these numbers first are wrecks in Northern Palm Beach, off Jupiter called the Zion Train/Esso Bonaire wreck trek and neighboring MG-111 and Hole-in-the-Wall. In a short span of a week or two, a similar number, comprised 50 to 60 fish have descended on a second set of wrecks, Mizpah and Danny, a few miles south off West Palm Beach. By early September, another wreck further south off Boynton Beach named the Castor completes the scene with the arrival of another 50 to 60 individuals.

In the last two consecutive seasons, we have seen surprising twist where the Castor wreck received the lion’s share around the later part of September. Both times, as the spawning season was near the end, number of fish present swelled to around 100 fish in 2013, with the 2014 season peaking out with nearly 150, the majority of which were fish that had pulled up or moved down the coast from both the Jupiter and West Palm Beach sites. The first shift in preferred locations may have been influenced by a string of cold-water upwelling’s that plagued the first half of the 2013 season. Considering goliaths are not fans of cold water, the upwelling’s (an event that takes place time to time along the Palm Beach Coast) may have pushed a number of fish off the Jupiter/West Palm Beach sites farther south than normal. It just so happens that in addition to Boynton Beach being Florida’s east coast most southern spawning site, water temps were less affected by the upwelling’s.

The 2014 season was a different matter. While the upwelling’s were less apparent, the presence of the Gulf Stream was also less apparent, leaving most of the summer months with little to no current. Perhaps, these fish knew something we didn’t. Witnessing this spectacle could cause some to believe the fish are no longer threatened, and have successfully made a comeback. To call it such may be as premature as calling a herd of American buffalo in game reserves a full recovery for the species.

Long road back

Twenty-five years ago, encounters with just one of these reef giants off Florida’s east coast was a considerable rarity. Around the rest of the state, the situation was not all that much different. Once highly abundant, particularly on distant wrecks far off shore in the southern Gulf of Mexico, the fish began to be beaten back by aggressive fishing practices during the mid 1980s. In a short few years, the fishery was so badly in decline, the federal government under the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Act, began work to close the fishery on goliath grouper completely.

By the time these protective measures were fully enacted in 1990, there were so few large goliaths left it would be some eight years (1998) before the first documented spawning aggregation would reappear in the southern Gulf of Mexico. And another three years (August 2001) before the first spawning aggregation comprised of 27 fish off Jupiter, Florida, would be seen again for the first time on the east coast in nearly three decades. But appearances can be deceiving, as a major portion of the entire regional population taking part in this ritual behavior is represented between this one zone off Florida’s east coast and a key number of sites in the southern Gulf of Mexico.

Add to that the reality that at one time, the Atlantic goliath grouper were once highly abundant in not only Florida, but also along the entire Central and South American Continental Shelf as far south as the southern edge of Brazil. Their historical range even spanned the entire Bahamas and Caribbean to as far away as Western Africa in the Gulf of Guinea. Our planet’s ever expanding human population and today’s highly efficient means to harvest fish from the oceans has made it more difficult than ever to keep fish stocks the world over from being pushed to complete collapse. The most heavily impacted are the dominant predators of the tropical reefs—namely the groupers, with goliath grouper taking the heaviest toll.

While our own management measures may have stopped the progression of the U.S. population of goliath grouper toward extinction, relentless fishing pressure elsewhere in their range alerted the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to list goliath grouper as “critically endangered.” The same year the fish was placed under its new protected status, the job of monitoring the recovery of this species was put into the hands of scientists at both the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and Florida State University (FSU). FSU’s Research Ecologist, Dr Chris Koenig, and his colleagues, began a detailed study of the fish’s natural history.

Understanding an enigma

Unraveling the story behind what makes these fish tick has led to remarkable discoveries. Like most reef dwelling species, including groupers, goliaths are broadcast spawners where a female releases a quantity of unfertilized eggs into the ...

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #64

- Läs mer om X-Ray Mag #64

- Log in to post comments