There is just something that always feels right about getting on a small airplane for the final leg of travel to begin a dive trip. In my mind, it almost guarantees the destination is somewhere amazing—a place that is so special that the large jets used in mass transit cannot even get to it. I departed the island of Mahé, the largest and most-populated island in the Seychelles, for the tiny island of Alphonse, with that giddy, childlike feeling in which I could not stop grinning. I looked around at my fellow passengers also destined for Alphonse, and I could see them smiling too.

Contributed by

Factfile

Brandi Mueller is a PADI IDC Staff Instructor and boat captain living in Micronesia. When she’s not teaching scuba or driving boats, she’s most happy traveling and being underwater with a camera. For more information, visit: Brandiunderwater.com.

SOURCES: alphonse-island.com, bluesafari.com, idcseychelles.com, islandconservationseychelles.com, seychelles.travel, wikipedia.org

As we flew away from Mahé, a beautiful granitic island in its own right, it took about an hour to fly 400km (250 miles) southwest over blue seas before we began to descend on a small coral atoll, just a speck of palm trees and sand that steadily got larger as we approached. I watched out the open cockpit windows as the pilots took us straight in, onto a clear-cut runway in the center of the island. My spontaneous grinning continued.

Below was a small section of the Seychelles’ outer islands, the Alphonse group. It consisted of Alphonse and St. François atolls. The deep water surrounding the atolls was a shadowy, dark navy, but the green and ivory specks of the islands were encircled by what I would like to call Seychelles’ blue—an abstract watercolor painting of every shade of blue imaginable, from the lightest pale blue to sapphire and indigo, with brush strokes of jade and light brown. The real-life painting showed the shallow depths of the lagoons lightening to turquoise and surrounded by white sand and green palm trees. I could not help but think, “Our planet is so gorgeous.”

Arrival

I was still smiling like a kid on Christmas when our plane landed on the island, which was just 1.8km long by 1.4km wide (1.12mi by 0.87mi), and out the window was a line of resort staff waving to us. We disembarked and were greeted with introductions and smiles (big smiles, but probably not as big as mine.) I was about to spend a week on an isolated island in the middle of the Indian Ocean visited by only a small number of people each year. And honestly, most visitors come to fish, not dive. (Crazy, I know!)

The Alphonse group of islands is known to have some of the best fly-fishing flats on earth. Obsessive fishermen (whom I found to be comparable to obsessive divers) travel halfway around the world to throw a fly at tarpon, bonefish, milkfish and giant trevally, among others (it’s catch-and-release only here). The Alphonse Resort was initially just a fishing lodge, but now has a full range of activities, including diving, snorkeling, kayaking, stand-up paddle boarding, nature walks and bike tours, a lovely spa, and plenty of other activities to keep anyone busy.

Getting around

Taken in a golf cart to my luxury bungalow with beachfront access, I learned that this was one of the fastest modes of transportation on the island. Sitting in front of my adorable A-frame bungalow was my personal transportation for the week—a beach cruiser bike with a basket (in lime green) with my name on it. I do not know if it was possible for my smile to get any bigger, but it did. I loved this place already.

Biking over to the restaurant and main bar area (also oceanfront), I joined the rest of the guests who had arrived for a fresh coconut and some information about the island. Other guests included a lovely family with two small girls from Botswana and a South African fishing TV show crew. (Well, I guess the fishing really is that good.)

I ventured over to the activity and dive center where my gear had already been delivered and made plans for the next day. I would be diving, of course… and the only one. (Seriously? I thought, who goes to pristine islands in the middle of the Indian Ocean and does not dive?!?! Answer: fishermen). I would find myself revisiting this question in my mind throughout the week, only to discover it was exactly what the fishermen (and fisherwomen) were saying about me.

Morning bliss

After waking up naturally by the golden light of dawn streaming through my curtains, I made a cup of coffee in my room and strolled out to the beach in front of my bungalow. While the other bungalows were not too far away, the gardening and landscaping made it feel as if I was the only person on a private island. Looking out at the water, I saw several turtles pop their heads above the surface for a breath and then disappear back underwater, but I could still make out their silhouettes in the clear, shallow water in front of me.

I leisurely made my way to breakfast, having ridden my bike only a few minutes before arriving, and enjoyed more coffee, along with yogurt with fresh fruit and a croissant and muffin. More hardy options were available as well, such as eggs made to order and other hot items.

Diving

Over at the dive center, my gear was already on the boat and my wetsuit folded and waiting for me. They had also sent a golf cart to pick up my (large) camera while I was at breakfast (it was too big to manage on my bike), and it also magically appeared on the boat waiting for me. Once I was ready, the boat headed out to a site called Car Wash. The fishermen had all left much earlier and the boat ride felt like we were heading out on an adventure into the unknown, with no other boats or people around. It was not unknown to the crew though, who gave an impressively accurate dive briefing of the site, even down to where we would see schools of certain fish.

Once underwater, it felt just as adventurous—there would be no hordes of other divers here, and no risk of another boat dropping a dozen tourists on top of us. It was just me and my guide, Rose, for hundreds of miles. How incredibly cool was that? And—the diving was excellent. As briefed, groups of bluefin trevally swam past us. As we passed a school of bluestripe snapper, Rose pointed out endemic Seychelles anemonefish, and there were massive pink gorgonian sea fans everywhere. The big surprise (not in the briefing) was a group of about eight massive bumphead parrotfish. Not bad for the check-out dive.

Currents and visibility are influenced by the tides, so to get the best conditions, the dive team suggested we dive once in the morning, take a long break, and then two dives later in the day. I was traveling alone, and somewhere along the line prior to arriving, I had mentioned it would be great to have a dive model. Just to start to describe how accommodating the staff was, they provided me with a dive model. On my next two dives, I had a dive guide and a dive model (and a quite good model at that).

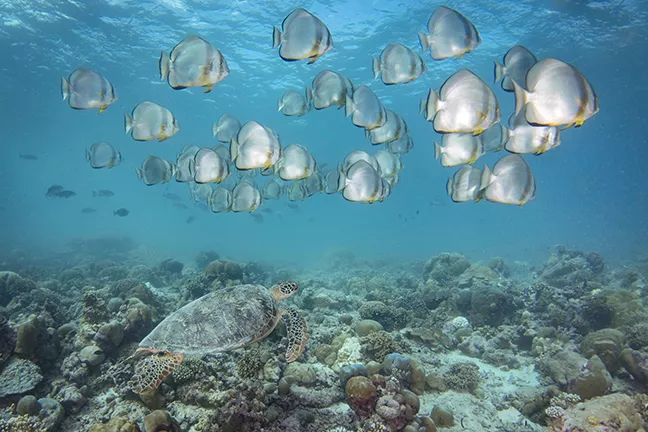

We visited the dive sites known as Abyss and Arcade, and my model posed with more schools of bluestripe snapper and yellowspot emperors. We swam over an old anchor that probably belonged to a ship that long ago hit the reef. A large school of barracuda passed by and friendly batfish followed us around like curious puppies, particularly on our safety stops where they seemed to hover right along with us until we returned to the surface.

After diving and a warm shower (in my lovely outdoor shower), I headed to the communal meeting point (the oceanfront bar) where the fishermen were telling tales of their bonefish and giant trevally catches. Soon after, I enjoyed a fantastic dinner under the stars before heading to sleep, with the sound of waves playing a natural soundtrack off in the distance.

Island life

I very quickly fell into a rhythm of waking up, making coffee to be sipped on the beach or on my patio, slowly making my way to breakfast and then riding my bike to the dive center. I was riding along, feeling ever so relaxed, when I rode past a rock and I did a double take. Backpedaling on the brakes of my cruiser bike, I stopped, slowly backed up, and to my right, was a giant Aldabra tortoise—on the side of the bike path!

Thinking nothing of the tourist gaping at it, the tortoise continued to munch on grass. The Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea) is one of only two giant tortoise species left in existence, the other being the Galapagos giant tortoise. While these two species are the last giant tortoise species on earth, they are not directly related. The Galapagos are most closely related to a tortoise species hailing from South America. The Aldabra are related to a species from Madagascar. Giant tortoises can live longer than 150 years, with some in captivity confirmed to be living over 200. Over 152,000 tortoises are thought to live in the Aldabra Atoll, which is a protected World Heritage Site.

While other islands’ tortoise populations were decimated long ago by sailors who brought them on ships to be kept for food and by habitat loss and destruction, some Aldabra tortoises survived on Aldabra Atoll. Today, they are being reintroduced to several outer islands, including Alphonse, which now has around 60 tortoises roaming the island.

Also on the island was a “tortoise pen,” in which little baby tortoises of different sizes were kept. I passed the pen daily on my way to the dive center. Adorable toy-sized giant tortoises could be seen chomping on leaves and slowly wandering about their enclosure. I learned later that all the babies in the pen were born on Alphonse and were usually found by the gardeners around the island. Keeping them in the pen offered protection because their shells are quite soft when they are very small, making them easy prey for birds, which are returning to the island, as well as invasive rats and cats, which island staff are actively trying to eradicate. Once the tortoises get larger and their shells harden, they are set free to roam the island.

Still in awe of my first giant-tortoise sighting, I excitedly told my story to the dive team who clearly were used to such tales, and one even replied that there was a tortoise that liked to live near her house on the island and was usually sitting right where she liked to park her bike. (Can I make a hashtag—#AlphonseIslandProblems?)

Back on the dive boat

After all my excitement, we were soon back on the boat (with my camera mysteriously picked up from my patio once again and appearing on the boat when I got there). The staff had suggested visibility might be a little low due to the tide, so I had my macro lens on my camera, ready to capture some of the small stuff around Alphonse. Needless to say, I was not disappointed. Hardly moving at all underwater, I saw eels being cleaned, porcelain crabs in anemones along with the endemic Seychelles anemonefish, and blennies, blennies and more blennies.

I also tried to get a few shots of a behavior I had noticed the day before. Swarms of anthias buzzed around the reefs, and as I got close, they would (as usual) hide in the crevasses of the reef… but I noticed they were going into holes occupied by moray eels. I had never before seen this symbiotic relationship in which dozens of pink, purple and orange anthias would crowd into a hole, sometimes even touching an eel which seemed to stand guard. The eels seemed to get upset with me and would quickly charge out and back into the hole when I came too close while taking a photo, as if they were protecting their anthias.

In the afternoon, we dived Boiler and Eagle Nest, and I had not one, but two amazing dive models: Chris, who worked at the activities and dive center, and his partner, Jenn, the absolutely phenomenal pastry chef on island (for real, I am still daydreaming about her beetroot panna cotta). Boiler was a forest of giant sea fans. They grew so tightly packed together that their shapes were altered by the other sea fans growing into them. Schools of fusiliers would whirl by, and on close inspection, the sea fans had longnose hawkfish and gobies living within.

In the evening, there was a presentation given by the resident staff of the Island Conservation Society (ICS), a Seychelles non-governmental organization. Several staff members live on the island year-round and conduct research on and around the island. They monitor the island’s seabird populations, and green and hawksbill turtle nesting; they also conduct coral reef surveys and have many other projects. It was amazing to hear about their conservation projects on Alphonse and several other outer islands. The Seychelles has over 50 percent of its land under nature conservation, and this is one of the groups helping to protect and restore the natural environments and advise on new projects taking place on the outer islands.

The perfect day

As the sun set on my third day at Alphonse, I sipped a perfect gin and tonic while watching the sky turn pink and reflected on what makes diving “good” at a certain location. There are some places and specific times where we go to see a certain animal or behavior: sharks, manta rays or coral spawning, etc. But there are so many places we visit just because the diving is “good,” having pretty reefs, lots of fish, maybe a turtle or an eagle ray sighting. I thought back on dive trips that were “good” in which I only saw maybe a turtle or two, or one ray, and a few sharks.

This day felt like it was all of the “good” diving most people experience in a lifetime—but jam-packed into one day. I took another sip and tried to remember what we had all seen. I was, for the third day in a row, the only diver. My guide was Lucy, one of the dive center’s managers, and she also agreed to be my model for the day. Our first dive was at a site called Pinnacles, which several staff had mentioned as their favorite.

Pinnacles

The boat dropped us off at the edge of the island where the current was flowing directly towards land and wrapping around it in both directions. As we descended into clear water, the amount of marine life below was stunning. A huge school of chubs lingered just below the surface, and closer to the sandy bottom were massive schools of bluestripe snappers and yellowspot emperors, filling the gaps between several rock pinnacles.

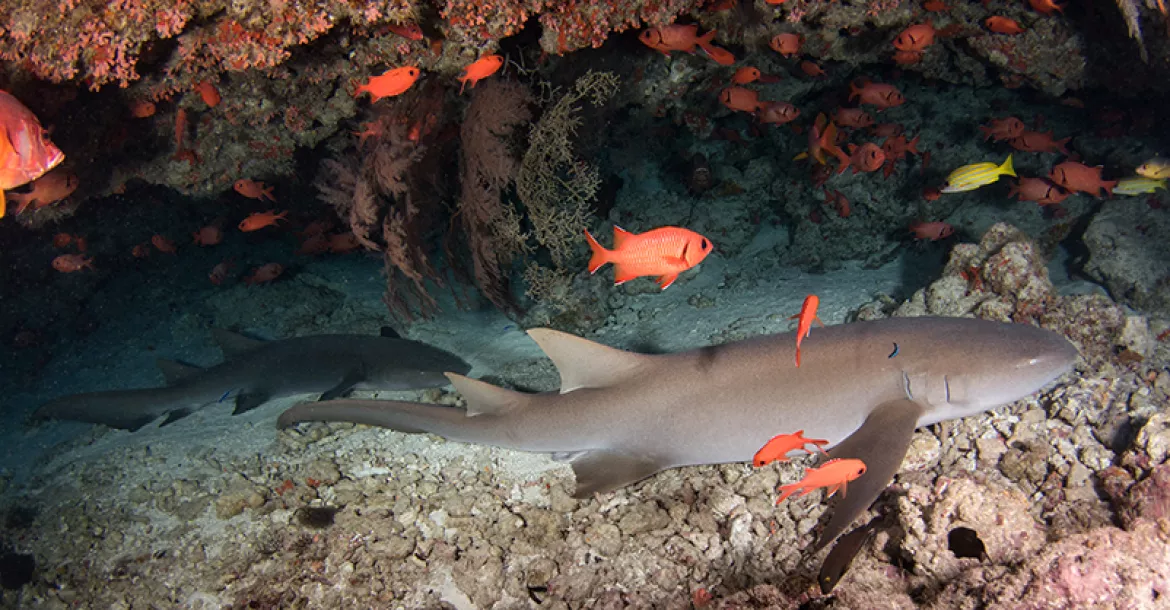

As we got closer to the coral-covered pinnacles, a few sea turtles swam from their sitting positions on the coral up to the surface, passing right by us. As one returned from taking a breath of air, it swam back down, passing right between Lucy and me. Under rock overhangs, there were numerous tawny nurse sharks.

It was nonstop action, with a turtle here and a shark there. Lucy had lined up behind a school of blackbar soldierfish for a photo when right behind her emerged an eagle ray. At another point in the dive, she swam through a space between two pinnacles and several bluefin trevallies swam right in front of her. A sweetlips, posing perfectly for the camera, seemed to get closer and closer, and we even had a giant trevally swim very close at the end of the dive.

Back on the boat, we motored over to the next dive site, but did not get far before we were surrounded by spinner dolphins. I asked if I could jump in and moments later, I was encircled by dolphins only for a moment before they swam off. Back on the boat, we started moving again and they were back. Once again I jumped in, only to see them for a few seconds before they took off again.

Napoleon and Hacksaw

Our next dive site, Napoleon, was a swirl of sea fans and fish, and as I continued to snap photos, I started to wonder how many photos of giant pink sea fans was too many.

Lunch was a bit different on this day; all of the resort guests met on an area of shallow sandflats at low tide for a BBQ-style lunch. Chairs and umbrellas for shade were set out as we ate together discussing the diving (and the fishing). One boat of guests had gone snorkeling, including the two youngest guests, Megan and Taylor. They told me about the dolphins they saw on the way (I had seen them too), the turtles they swam with, and how they spent the morning collecting trash on the beach for an art project. I was very excited to see this art project when it was finished.

It was pretty fantastic to be on an exposed bit of sand, which is usually covered with water, and having lunch. Once again, I was surrounded by that jaw-dropping “Seychelles’ blue,” with the water changing shades of blue from dark to light, concluding its spectrum with the white sand. It reminded me that we were on this remote, isolated island, upon which so few people ever step foot, devouring BBQ chicken pitas and some of the best brownies I have ever tasted.

Soon, we were back on the boat, about to dive a site called Hacksaw. Lucy back rolled into the water first, and she came back up and yelled “Silvertip!” I looked at our boat captain and wondered if that was a “get-in-the-water-right-now” sort of silvertip call or a “stay-on-the-boat, there-is-a-silvertip-shark-charging-me” sort of call. But I did not ask or wait for more explanation, I back rolled into the water and headed straight down—there was a silvertip to photograph!

I did not expect the shark to stick around, but it did, for about five minutes, and was joined by two others. Continuing the dive, we headed into another patch of sea fans, and the silvertip sharks seemed to follow us for a bit. I thought maybe I would get the perfect shot of a silvertip shark with pink sea fans behind, but they did not cooperate and soon left us. During the dive, we spotted an octopus, a peacock mantis shrimp and many schools of fish.

At the end of the day, we had seen two species of sea turtles, three species of shark, eagle rays, dolphins, giant trevally, huge schools of snapper, octopus, mantis shrimp, sweetlips and batfish, and enjoyed a lunch on an isolated sandflat in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Not a bad day… not a bad day at all.

Spoiled

It was around this point that I started to get spoiled. Underwater, I had passed up photos of turtles, batfish and nurse sharks just because I already had so many. Our first dive at a site called Arcade was indeed a turtle city. Every few feet, there was another green or hawksbill turtle—some under ledges scratching their shells, some at cleaning stations getting a bath, others in the water column going up for air, others coming back down, and one even seemed to slowly lead me to a school of batfish, so it could have its photo taken with them.

My guide, Rose, had the cutest batfish follow her the whole dive, which made me smile; it just stayed a few feet behind her, continuously looking like it was about to nip at her fins. I pointed it out to her, and she gave a heart hand signal underwater. As our dive ended, we ascended to our safety stop, and her batfish buddy seemed to have called all its friends. We had maybe two dozen circling us.

Pinnacles was so good the day before that we went back, and it did not disappoint. Once again there were plenty of nurse sharks, schools of snapper, several Napoleon wrasse, which would not get close enough for a good photo, and at the end of the dive, a fever of marbled stingrays. Just another day of diving around Alphonse Atoll…

Change of scene

A few other divers joined the boat doing an advanced open water class, and we dived Arina, a site in the lagoon of St. François Atoll. There were schools of humpback snapper, two eagle rays, which snuck up behind me, a school of bigeye trevally and lots of fish.

Our second dive was back at East Side Wall. This time, I used my wide-angle lens. A cold thermocline crept in early in the dive and would not go away. I found myself shivering and was just about to call off the dive around 40 minutes in, when a school of bumphead parrotfish came straight for us. I took one shot and they turned around to swim away, but one turned back around towards me. It found a piece of coral to bite, and while it was eating, it let me get quite close. When it was finished, it looked right at me, and then, swam away. We also had a glimpse of a lemon shark.

Our day finished with sunset drinks at the beach bar, a short bike ride through the jungle, ending near the western corner of the island. Mingling with other guests, we sipped drinks and nibbled on fresh fish tacos and dried plantains, discussing our daily adventures and how beautiful and unique this place was. After the sun set, we rode our bikes back for dinner, and I found myself on my beach looking up at a million stars before calling it a night.

Macro life

On my last day of diving, I decided to shoot macro because the weather looked dark and stormy. At a site called Theater, I found a large pufferfish, with bite marks on its face, being cleaned by several wrasse. The cleaner wrasse moved around the red, exposed, fleshy areas near the eye and mouth of the fish. I also found several longnose hawkfish in the sea fans. An octopus came out to inspect us, and at the very end, of course, a manta swam overhead (these things always happen when shooting macro).

FADs

The last dive was a special dive. The students were doing a Dive Against Debris, and the plan was to try and remove a FAD (fishing aggregation device). Large commercial fishing boats in the Indian Ocean are known to send out these floating platforms with lines or nets hanging from them to attract fish. Many are equipped with satellite GPS systems and fish finders to signal to the larger boats when large schools of fish are below.

Unfortunately, a lot get “lost” and drift up on the reefs and beaches of Alphonse (and other islands). They can entangle sharks, rays, turtles and fish, and can be left as piles of rubbish on beaches or shallow reefs. Lucy had told me about the FAD problem, and when she said we were going to go and try to remove one, I also thought that involved looking for one, as in, we know they are out there, maybe we will come across one and be able to remove it.

I was wrong. This was not a “maybe-we-will-find-one” mission, the FADs were apparently so numerous around Alphonse that we saw three within a few hundred feet of each other. We managed to remove two in just under an hour, with a group of about eight people. I was shocked at how severe the FAD problem was here, yet it seemed unknown to the rest of the world.

Turning beach debris into art

Back at the dive center, the amazing staff cleaned my gear and hung it to dry (and my camera disappeared and reappeared at my bungalow). I also noticed a new piece of artwork on the walls. Made from plastic and garbage found on the beach. Megan and Taylor, the youngest guests of Alphonse, had turned discarded flip-flops, bottle caps, a yoga mat, cigarette lighters and toothbrushes into a palm tree collage. Their artwork was hung with a humpback whale, a turtle, and other designs made by other guests—such a cool project, and their palm tree turned out so well!

Everyone met at the oceanfront bar for drinks and storytelling from the final fishing day. I found myself again contemplating how remote we were, the amazing service of the resort, and the variety of things you can do on the island. Over 100 staff reside on the island, and the resort can house around 70 guests—although often, it is much less. The staff paid attention to so many little details, such as the lights at night on the bungalows and around the island. They were green and red, so that newly hatched turtles would not get confused and crawl inland towards white lights instead of out to sea. It seemed like the staff anticipated what I needed (sometimes even before I realized I needed it) and nothing was too much to ask.

The resort also offered fishing and diving trips to other outer islands, including Astove, Cosmoledo and Poivre Atolls. The same thought kept crossing my mind, “What an amazing place.” Also, “How do I get back here again? How can I get to the other outer islands? I wonder if they need a dishwasher?”

The last day: Island exploration

On the previous night at dinner, Sam and Lucy had suggested a guided island bike tour—something most guests did the first few days they were on island, but my diving schedule did not allow time for it. I eagerly said yes, but woke up to stormy skies, and I wondered if anyone would want to ride around in the rain with me.

After breakfast, I headed to the dive center in a light drizzle, passing three tortoises munching on grass in the rain. I gave them each a wave and a silent goodbye. I figured that if my tour was cancelled, I would say goodbye to the dive team as well, but Sam was there and ready to show me the island, so off we went.

Before my trip, I had read up on some of the history of the island, and Sam reiterated that it was originally a coconut plantation, with only a few people living on the island. They had cut down most of the natural vegetation to make way for coconut palms, and they had mined the island for guano, which was used to fertilize the palms, to the detriment of the topsoil. As a result, many birds stopped breeding on the island because the vegetation in which they nested was gone. In addition, turtle eggs (and bird eggs) were harvested, causing a decrease in populations.

Sam also showed me the gardens where much of the food consumed on the island was grown. Several gardeners worked full time to grow fruits and vegetables. He also took me to the island’s solar plant where almost all of the power needed to operate the island was harvested from the sun.

Alphonse Resort really seemed to be the epitome of ecotourism. It felt like the resort had done it right and this would be an excellent model for other companies in the tourism industry to follow. Admittedly, it is not a budget destination, but one is paying for an island that is being rehabilitated. While visitors get luxury and adventure in a pristine environment, the island is being cared for and given a chance to return to its natural state, as evidenced by the return of the birds and turtles.

The isolation of the outer islands of Seychelles makes them easy places for illegal fishing and poaching. One way to deter turtle and seabird egg poachers is to have people on the island year-round (like tourists). Of course, this may mean that the poachers just go to another island, but at least some islands will be safe havens for the birds and turtles.

And on Alphonse, it is apparent that this approach is working, as I have never seen so many turtles. In the mornings, when I walked out to the beach, at any given moment, two or three sea turtle heads would be peeking out of the water to grab a breath of air. The dark shadows of sea turtles diving and gliding past the shoreline were everywhere. Birds were constantly seen circling the island and also nesting.

As the days passed, full of activities, but still at the relaxing pace of the island, one could almost feel the collective sadness among the guests as we realized we would soon have to leave this wonderful island. We were gathered up on Saturday afternoon, leaving our bikes behind and returning to the runway in golf carts. I suppose my bike soon had another name on it and someone else was riding it in paradise.

The IDC plane came, and we hugged the staff on our way out (in my head, I was already plotting how and when I could return to visit Alphonse and the other outer islands). I got on the plane, craned my neck to see out the window and watched the island disappear into the blue. Still smiling, I thought, “What an amazing place.” ■

Special thanks go to Alphonse Island Resort (alphonse-island.com).