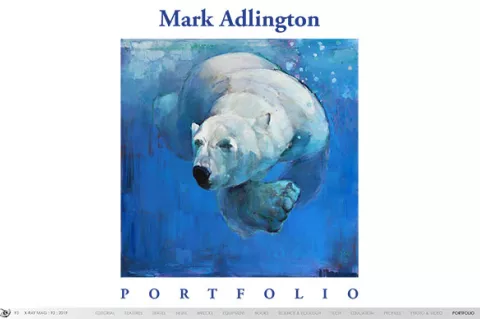

Mark Adlington Portfolio

British artist, painter and sculptor Mark Adlington has travelled to the wild and remote corners of the world, studying and sketching wild animals in their natural habitats, and from these impressions, created large, vivid, spellbinding paintings and fluid drawings featuring the dynamic movement and magnificent presence of some of the earth’s most threatened species. His underwater paintings feature polar bears, otters and seals.

X-Ray Mag interviewed the artist to gain insight into his art and perspectives of these animals.

Contributed by

Factfile

Follow the artist on instagram.com/markadlington or visit his website at: markadlington.com.

To order prints, visit: magnoliabox.com, greatbigcanvas.com, myartprints.co.uk.

In the USA: allposters.com, art.com, fineartamerica.com.

X-RAY MAG: Tell us about yourself, your background and how you became an artist.

MA: Like all small children, I loved to draw and paint. My mother was a portrait painter though, so unlike many kids, I was aware from an early age that adults too, could enjoy messing about with paint, and that probably encouraged me to continue and take it a little more seriously. On some level, I probably always knew that I would become an artist. But at 13, I went to a very academic school, which regarded art as child’s play. So, it was not until I had been through the whole process of university and a few years working for an auction house that I had the courage to go back to art school and start again!

X-RAY MAG: Why marine mammals? How did you come to these underwater themes in your art?

MA: I grew up on the edge of the Atlantic, just a few yards from the ocean in one of Ireland’s most beautiful and remote bays. I was obsessed by nature and all wildlife from a very early age, but my first great animal love was seals. Our bay is rare in that it has the shelter and low tide haul-outs for harbour seals, but is close enough to the Atlantic proper to be frequented by the much larger grey seals as well. There is often a young grey seal resting on the rocks with its smaller cousins.

I have always understood why so many legends and myths (particularly in Celtic traditions) surround seals. There is something miraculous about the fact that they seem so familiar to us, and yet can go between two worlds/elements—at home above and below the surface.

I used to spend hours swimming with them, or just sitting in a rowing boat, waiting to see where the next heads would pop up. Once safely in the water, they feel far more confident and seem as curious and fascinated by us as we are by them. I noticed the same phenomenon with the magnificent walruses in Svalbard when I was there—another wonderful animal that I would love to paint.

Along the shoreline, and even on the edge of our garden, there were otters. They were, and continue to be, more elusive, but have always held a very special place in my heart.

Farther out to sea, we would often spot porpoises, dolphins and sometimes even basking sharks or whales.

X-RAY MAG: How did you come to these themes and how did you develop your style of painting?

MA: One of the eccentricities of our family home was that it contained a number of Chinese paintings by very well-known Chinese artists of the 20th century. So for me, the idea of placing a drawing or painting of an animal on a blank page without landscape or background seemed completely normal—though I now realise this is a difficult concept for many, being so different from the European tradition.

So, in one sense, I have always, for purely painterly reasons, been attracted to water, ice and desert as landscapes, as they give me the whole animal, unencumbered by grasses, trees or foliage. For this reason, when I made my first show of studies of otters and seals, I made the somewhat unconventional decision not to paint the water itself, but to imply it within the figure of the weightless animal.

X-RAY MAG: What is your artistic method or creative process?

MA: Speed is an essential part of my creative process. I have always had a tendency to overwork, and like many artists, have great difficulty in knowing when to stop. W.C. Fields famously advised, “Never work with animals or children.” But in my case, drawing animals from life, which so often has to be done with great speed and simplicity, has given me an invaluable insight into mark-making and reaching for the essential essence of a subject.

I try to spend as much time as possible with my subjects, observing, waiting, watching and scribbling in sketchbooks. Then, in an ideal world, any work that is made in the studio will happen with energy and speed. Of course, the reality is that we do not live in an ideal world, and sometimes, I can get stuck on a painting for many weeks, losing the path completely before (hopefully) wrestling it back to the original idea. For this reason, I have always enjoyed working on paper, where it is very quickly clear whether to tear it up and try again, or leave it well alone.

I am very random with both materials and technique, and enjoy adapting both to the subject matter. When painting the underwater polar bears for example, I used a bizarre combination of Moroccan pigments and household bleach to try and capture the surrounding air bubbles and displaced water around the arctic giants.

X-RAY MAG: What is your relationship to the underwater world and coral reefs? Are you a scuba diver or a snorkeller, and how have your experiences underwater influenced your art? In your relationship with reefs and the sea, where have you had your favourite experiences?

MA: Despite my early and ongoing relationship with the sea and the rich coastal life of the Irish Atlantic shore, I have never learned to scuba dive. I spent my whole childhood gazing into rock pools and trying to see the seals in the bay underwater, and have always loved snorkelling or floating above the bay in a little boat on a calm day, spotting fish, crab and lobster below.

However, when I was working with the desert fauna of the Arabian peninsula in Oman, I was offered (quite illegally, I am sure) the chance to make two 40-minute “trial dives” with a bare minimum of swimming pool training. It is an experience I will never forget. Becoming the man from Atlantis, and being able to follow the breathtaking fish and turtles of the Arabian Sea in their own element was one of the highlights of my life. I was like a puppy on acid, on a high that stayed with me for months. I swore that I would take the necessary exams, but somehow have failed to find the time. It will happen though, of that I am sure.

With the bigger marine mammals, especially the polar bear, while I was lucky enough to spend time in Svalbard with many wild bears and watch them swimming between ice floes and rocky islands, I realised that swimming underwater with one of the earth’s largest carnivores was going to be beyond me. I have very mixed feelings about zoos (despite their often undervalued contributions to conservation and education) but they are, of course, hugely useful for wildlife artists. Being of partly Danish heritage, I was lucky enough to have family to stay with while studying the bears underwater at the Copenhagen Zoo, where there is the possibility to watch the polar bears diving and swimming below the surface from many interesting angles. This experience became an essential component of my book, Painting the Ice Bear. It would have been totally wrong to carry out a visual investigation of a marine mammal entirely from above the surface!

X-RAY MAG: What are your thoughts on ocean conservation and coral reef management and how does your artwork relate to these issues?

MA: Much of my life’s work has been connected with conservation, and many of my principal subjects—the Arabian leopard, European bison and Przewalski horse, for example—are, or have been, a hair’s breadth from extinction. I have had little direct connection with the coral reefs, but a good friend devoted ten years of her life to sailing the world’s oceans monitoring the shocking devastation wreaked by warming seas, so I was aware of these issues long before they became common knowledge.

The bay that I grew up in was at the forefront of a fierce battle between conservation and local employment when the fish farming industry began to install salmon rings locally, so I am also aware of the political difficulties surrounding all attempts at environmental protection. In Svalbard, I was part of a team clearing plastic from the shore on uninhabited islands hundreds of miles from the nearest human population. As these issues loom larger and larger in the public consciousness, I think the tide is finally turning and am hopeful that dramatic and long overdue action will finally take place to combat the destruction wrought on the planet’s oceans by human activity.

X-RAY MAG: What is the message or experience you want viewers of your artwork to have or understand?

MA: I am endlessly amazed by wild animals, and have infinite patience when it comes to looking for or observing them. So while, like all artists, my principal concerns in the studio are often abstract or formal ones, and the solving of painterly conundrums, I suppose that what I am trying to communicate is my own complete passion, respect and wonder in the presence of these miraculous creatures. And because I work in series, sometimes focussing on one species for many years at a time, I think, at best, there is an almost shamanic element to my practice, which I would hope communicates itself to the viewer.

X-RAY MAG: What are the challenges and benefits of being an artist today?

MA: In many ways, the challenges and benefits of being an artist today remain much as they always have been: the probability of relative impecuniousness, balanced with the freedom (and loneliness) of working for and by yourself. I would say that the Internet and the advent of social media have made it far easier to bring artwork to new and like-minded audiences than ever before. So, despite the time drain and additional pressure of platforms like Instagram and Facebook, for artists—especially artists with specific subject matter—they can be uniquely useful.

X-RAY MAG: How do people respond to your works?

MA: Following on from the previous question, I would say that until the advent of social media, one of the sadnesses of being a painter, and selling works through a gallery, was that you almost never got to see the effect that the work had on people. Now, all of that has changed, of course, and I have made wonderful contacts and friends in remote places across the world entirely through images of paintings shared on mobile phones. Many years ago, when it was a very avant-garde idea, the gallery sent out a video instead of a catalogue to promote an exhibition I made about the endangered alpine Ibex. The combination of mountain-climbing adventure, wildlife, and an adult making a huge mess in a studio, proved irresistible to kids. I know for a fact that the film was a massive hit with the under-fives, as parents told me they had to run it again and again. My last exhibition, which was a series of large portraits of specific wild African elephants I had got to know in Kenya, was described many times as “moving,” which I, in turn, was very moved by.

X-RAY MAG: What are your upcoming projects or events?

MA: I am currently on the final year of a long project working with lions, which I have been studying in Namibia and Kenya, and hope to bring out a book and exhibition next year. Somewhere in my mind’s eye though, I can already see a book on the Celtic shore of my childhood, which will focus again on seals above and below the surface. So, watch this space! ■

I am endlessly amazed by wild animals, and have infinite patience when it comes to looking for or observing them . . . I suppose that what I am trying to communicate is my own complete passion, respect and wonder in the presence of these miraculous creatures.

— Mark Adlington