Andy Nichols Portfolio

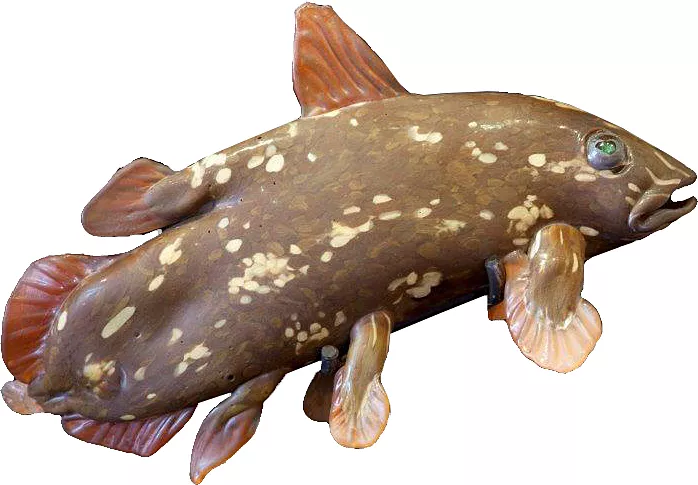

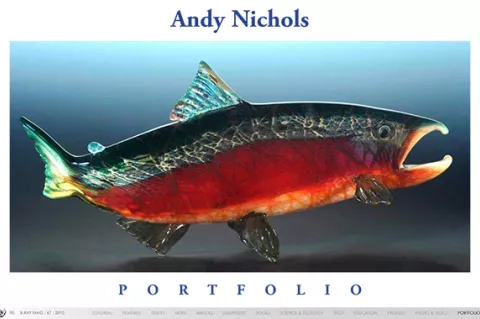

American artist Andy Nichols creates vibrant sculptures of migrating salmon, fish and coral reefs in blown glass. After 20 years in the restaurant business, he opened his own glass studio in the Dalles, Oregon, where he continues to develop his own unique, signature style.

Contributed by

X-RAY MAG: Tell us about your background and how you became a glass artist.

AN: Well, art is sort of my second career. I actually studied art in school and my mother was an incredible artist, so we kids grew up in a house full of just-about-whatever-you-wanted-to-do-it-could-be-done attitude. After school, I really didn’t know what I was going to do, so I fell into the restaurant business, and I did restaurant work for about 20 years. While I was doing that I continued to do some artwork on the side as a hobby.

When I was in high school, my mother owned a stained glass studio, so I was around that quite a bit. I learned how to do stained glass windows and some fusing.

Then I took a glassblowing class back in the late ‘90s, and it was just the most fascinating thing to me. In all the other art forms I had done, like painting and stained glass, you could take your time… you could stop, step back and look at it... maybe come back to it tomorrow. But glassblowing was an immediate thing. You have that hot glass at the end of a pipe—it just has to be something, and you couldn’t wait around. It was the most difficult thing I had ever tried. I think the challenge just drove me to want to do it.

X-RAY MAG: Tell us how you developed your glass sculptures and artistic style. How did you come to focus on ocean-related themes in your work featuring forms of fish and coral reefs?

AN: Luckily, the restaurant I worked for was owned by a medium-sized company with several hotels and restaurants. When I got my little glassblowing shop going in my garage, which I ran on the side for about two years as a hobby, and I left the restaurant business, the people I worked for realized that this was my passion. So, they actually came around to help support me and started buying glass for their hotels and restaurants.

I think that part of the connection I have with ocean-related stuff came from a time when I worked for two years in 1988 and 1990 on the Oregon coast. I was just fascinated with the ocean.

When I was a kid, I wanted to be an oceanographer and took some classes in the subject. My family had a beach cabin in a small town on the Oregon coast. We would go fishing in the ocean, and I just loved it.

When I was working at a restaurant on the coast, I took scuba classes and got certified. Most of my scuba diving was in the Puget Sound area (in Washington State) up near Seattle. So when I started doing glass, I thought, well, one, I love ocean-related things—fish and texture and color—and two, it seemed that there was a good market for it.

My very first big job was a big chandelier for one of my previous employers’ premier hotels on Cannon Beach. It was the very first job where I used blown clusters of seashell-shaped pieces. So that is how it all got started.

My shell sculptures developed along the way, with different textures and in the way they were shaped and how they opened. The more you look at ocean life and how things are tightly packed together, the more you see that some things are new, like babies, and some things are opening up. Then I started seeing how things fit together technically.

X-RAY MAG: What is your artistic process? How did you develop your glass salmon?

I think that having the scuba diving experience really sparked my imagination, but I think it takes more than that—it takes studying it. It’s so funny, when I first started making fish in my garage, just because I loved fish, they weren’t really any type of fish—it was just a fish idea. I remember my kids were young at the time, and they said, “Dad, your fish really sort of suck. Why are you making them?” And I said, “Well, because I think they’re fun!”

Then, after about two years, I thought my fish were getting better. I set out to show one of my fish sculptures to guy who had a brewery store in the next town over, where they sold beer supplies and glassware. The guy wasn’t there but an elderly man was at the counter, and he asked, “Well, what do you want?” and I said, “Well I came to show this guy what I do,” and he said, “Well, show me.”

So I unwrapped the fish and he looked at it and said, “What the heck? What is that?” and I said, “It’s a fish!” And he said, “I’ve never seen a fish like that.” And I said, “Well, it’s an artistic interpretation.” And he said, “You need to go home and do some homework.” Turns out he was a fish biologist, retired. And I thought, “You know, you might be right.”

And from that point, I really started collecting books and articles and magazines and posters… mostly with a focus on salmon, everywhere I went. The Dalles, where I live, is on the Columbia River, and the Columbia River Gorge is just quite beautiful. So I am right in the heart of salmon country.

I soon realized, the more you get to know them [the salmon], the better you understand them. Where does that fin really go and how does it move? Now, many who come in to see my salmon sculptures say, “Wow, your fish are there! You got it!” And I say, “Oh, not even close! I’m on this journey and there are some things about them that I’ve not figured out or captured yet.” It’s a lifetime journey. I’ll understand them someday, maybe, but if I can capture the shape of a salmon’s mouth or the wiggle of the fish, it gets me excited, because I feel like I’ve captured a little bit of the essence of their world.

X-RAY MAG: Do you go out and study the salmon in nature?

AN: About six years ago a friend of mine found for me this really cool underwater live feed video camera. It’s not a filming camera but it’s got a live feed. It has 60ft of cable with which you can lower a camera down and it has a monitor and a battery pack. It even has night vision. So you can actually go and just get down in there and watch the salmon. I use it when I go camping, in small streams and smaller rivers where the water is really clear. You can put that camera in places and just watch the fish come right up through the rocks. I’ve taken it to fish hatcheries and watched a bunch of fish close up, wiggling together and going in and out of the picture.

I met a marine biologist, a young lady in our area. She came to the studio and we collaborated on a salmon skeleton project. She pulled up some information for me and really explained the anatomy of the fish. The challenge was how do I take glass and make something like that?

X-RAY MAG: What is the process in creating a glass fish sculpture?

AN: Well, it’s very tricky. The kind of glassblowing I do is off-hand glassblowing. Basically there’s a hot furnace with liquid glass in it at the studio, and then we fire up another gas-fired furnace to keep it hot. The fish is four dips of clear glass with glass colors, mostly powders and frits (glass bits) added into the layers. I use some silver leaf on most of the fish.

Basically you take the blow-pipe and gather some glass on the end of the pipe. Some people ask me, “Well, do you have a mold for the fish?” And I say, “No, it’s basically wet newspaper and my hands that sort of squeeze the glass and pull on it and cut it to achieve that shape.”

The fish takes about two hours. In the first hour, it’s not very fish-like—it’s just a lump of glass, then I put all the colors in, and then I blow that out into a bubble and stretch it. All the fins, except for the tail fin, are added on separately. And this is where it gets tricky and this is where if I had an assistant on the fish, it would help me, but I’ve been able to achieve the fish without any help so far, and for the size they are, that works, but if they got any bigger or more complicated, it would require more people.

People ask, “How long does it take to make a fish?” And I usually say, “An hour and 45 minutes to two hours.” And they say, “Well, that’s really fast and looks so complicated.” And I remind them that in the glassblowing world, you have to keep it hot the whole time. You can’t let it cool or the glass will break. So I can only stay out of the furnace for about 40 seconds. So for almost two hours, every 40 seconds, I am in the furnace and out of the furnace. It’s really a lot of standing up and sitting down and torching. Normally, you’re all sweaty and wet after a fish, no matter what time of year.

Then the fish sculpture goes into a kiln to slow cool over night. So whatever product I make during the day, I don’t see it or touch it until the next day. That process is called annealing. Blown glass has to be annealed, and the thicker the glass, the longer the annealing.

X-RAY MAG: How does your experience scuba diving influence your artwork and where are your favorite places to dive?

When I moved to the Dalles, I was sort of away from my scuba diving. I found that as a young artist I didn’t have a lot of money to do that, so I sort of fell out of my whole scuba diving thing. About three or four years ago, it was driving me nuts and I went and took a refresher class. And then about a year-and-a-half ago, I bought new gear, because all my gear was really old. For the first time, I bought a drysuit, and I have a whole new set up that I have not used yet. So, my goal is to get back in the water and get inspired a little more.

There’s some beautiful places in the Puget Sound area where the water clarity is pretty good, certain times of the year. There’s really a ton of marine life and things to see. I’ve only done a little bit of warm-water diving, not as much.

So my goal is to get back into the water, and because the artwork has sort of developed while I have not been diving, I have some really fun ideas that I want to try that I have not tried. For example, I made a big 4x6ft wall hanging with 450 of blown glass shell pieces, along with some cast starfish. People are just amazed when they see it and ask, “What are those? Are they real?” and they have to go look at them and touch them.

I really want to put these glass forms back in the ocean, film them and see what they look like. My goal is to take hundreds or thousands of pieces and build a structure that would look as if the forms were stuck to a rock or a formation underwater, and then light it up. It would be a mini-underwater gallery show, but not permanent. The soft glow of those forms underwater would be really spectacular.

X-RAY MAG: What are the challenges and benefits of being an artist today?

AN: It’s funny, Seattle is really close by, and it’s really the hub of glassblowing in the world right now. It’s really a great place for a lot of glassblowers, and I am sort of on the outskirts. I’ve had people say to me, “Well, you haven’t worked with Dale Chihuly,” or, “You haven’t worked with one of his spin-offs…” It’s really a who-you-know kind of thing.

The glass community sometimes is really small. Many glass artists may take classes together or watch each other. I guess I am proud of the fact that I’ve never seen anyone make a fish yet. It was all trial and error for me, and I think that it makes my fish different from anybody else’s. I worked really hard to create fish over a long period of time. Perhaps I would have gotten a lot better, faster, if I had worked with those people in Seattle. But in a way, it gives me something a bit different.

X-RAY MAG: Do you feel like you have to keep coming up with something new?

AN: Yes, I think like in any business—and I probably picked this up in the restaurant business—you can’t have the same menu all the time or people will go to another restaurant. It really has to be fresh. You have to stay up with what’s happening, you have to have new items, and it needs to change and evolve all the time.

One of the other challenges I face is that I’m not a fast typist and so much of the business requires being in the office to communicate and write proposals or network. My sister is a really cool encaustic artist/painter and she’s really good at media. So she’s just miles ahead of me on social networking and promoting herself. She might spend one-and-a-half to two hours on the computer or in the office, whereas I am more likely to say, “I just want to go build things.”

X-RAY MAG: What are your thoughts on ocean and freshwater conservation and how does your artwork relate to these issues?

AN: People often say, “Oh, you must fish a lot.” And I say, “No, I don’t anymore.” I want to get down there and get with the fish, but I don’t want to fish anymore. Our world is changing quite a bit, and I feel for the fish. The Columbia River has a whole bunch of damns on it that make it hard for the fish to do their normal thing. There are chemicals and run-off from all the farming around here that makes life a challenge for the fish.

There are two different groups that I help and donate to. One of them is called Water Watch. I donate a glass fish every year to their auction. Water Watch is a water environmental group that tries to educate and help with water quality and the survival of the stock, the fish. They’ve taken out a couple of small damns. There are small damns on little rivers in Oregon used to generate power, but they don’t anymore, and the damns never had fish ladders, so the fish never got beyond them. [Water Watch] worked hard to take out those damns and get those steams back to normal.

The other group is called the Coastal Conservation Association. They help with coastal issues, garbage, how we use the beaches, crabbing and fishing techniques, to make sure we are doing it the best way we can.

There was a really good effort I heard about, and I was so excited, I wanted to know more about it. There was some money that was found by the NOAA organization, and NOAA actually went out and hired a couple of boats to go pick up ghost crab pots. In the last 50 years, crabbing has become really big business on the upper west coast. A lot of people don’t know this, but a lot of crab pots are lost, and then animals get caught in them and can’t get out. It’s a sad thing. So NOAA went out with really cool technical equipment and looked for ghost pots.

Humans are a crazy group. We take a lot, and we don’t think about what’s best, or about the longevity of the things we enjoy, or even about what we eat.

X-RAY MAG: How has your experience in the restaurant business helped you in the art world?

AN: The restaurant business is really a crazy business. It’s very fast-paced and to make money at it is very difficult. You need good volume, and you have to have really tight controls on your food and labor costs to really make it work.

Those ideas were really ingrained in me. So when I started doing glass, I noticed in other glass studios, there were people standing around to open the door, or four people wanting to help the artist, but only helping a little bit. And I kept thinking, “Who’s paying for these people?” That’s a lot of wasted time.

So when I started with my own studio I thought well, if I had a counter-weight on my lid, I could open it up with one hand, or if I had a hanger, I could hang it up and go grab something else and come back… little things like that. Do all you can by yourself until you REALLY have to have a second person.

The other thing I learned working in the restaurant business in the hotels, which really were trying to have a fancy place, crunching the numbers on the spreadsheet was not what the owner advised. He said, “Stop. No, just go out there and make the best food and have the best service ever, every single time. If you do that, the money will come.”

So I really realized that it if you work really hard to have something nice and you do it well, the money will come. I like money, but I’m really motivated by just making good art. I don’t really worry about the money, because I think that through my passion and just the love of it, it will happen. And I always believe that, “If you build it right, they will come.” But it has to be right, it has to be really good, and it has be good all the time.

X-RAY MAG: What feedback or insights have you gained from the process of showing your work to various audiences?

AN: I love the idea of sharing the experience of glassblowing with people, especially young people, because a lot of people don’t get to see glassblowing, and it really can open their minds. These days, in our area, there’s not a lot of money in the schools for things like the arts, so we do field trips for kids from either grade school or high school. Kids can watch glassblowing demonstrations at our viewing counter at a you-can-touch-me distance, and then I explain what’s happening. ■

For more information about the artist, visit: www.nicholsartglass.com.

It’s a lifetime journey. I’ll understand them someday, maybe, but if I can capture the shape of a salmon’s mouth or the wiggle of the fish, it gets me excited, because I feel like I’ve captured a little bit of the essence of their world.

— Andy Nichols

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #67

- Læs mere om X-Ray Mag #67

- Log ind for at skrive kommentarer