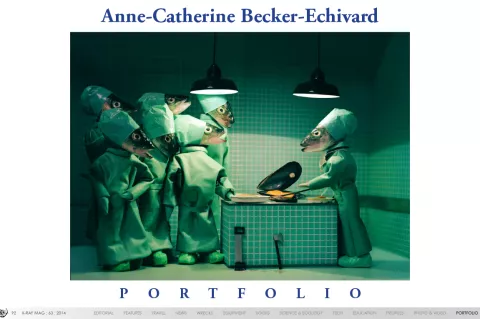

Anne-Catherine Becker-Echivard Portfolio

Merging humanity and animality in art is a device that can be traced back to the bestiary art and stories of the Medieval era, a time when mythical beasts combining animal and human characteristics were born and locked into our collective consciousness.1

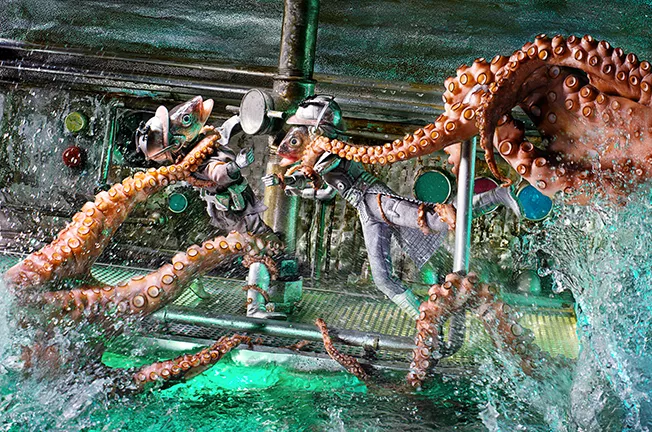

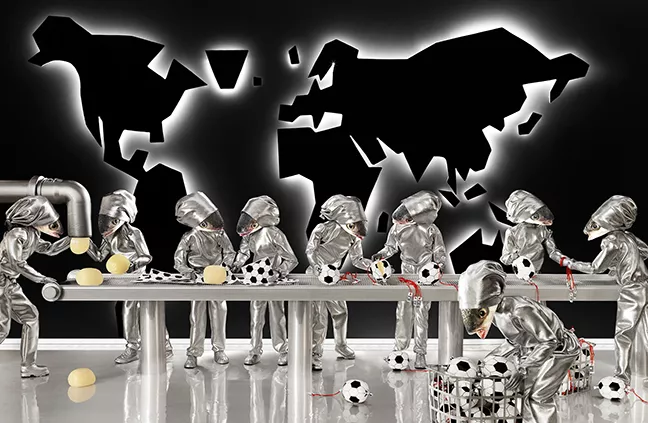

French artist Anne-Catherine Becker-Echivard‘s surreal artworks give us hints of these undercurrents, as she creates meticulously detailed dioramas of humanity using actual fish heads for faces in compelling scenes that address issues from profound political controversy to bizarre and humorous expressions of daily life to the downright absurd.

Contributed by

Factfile

SOURCES:

[1] Wikipedia.org; Artistbestiary.wordpress.com

[2] DTmag.com

[3] Greenpeace.org

[4] Education.NationalGeographic.com

[5] Greenpeace.org

[6] Finearttips.com

[7] Wikipedia.org

X-RAY MAG: Tell us about yourself, your background and how you became an artist.

ACBE: I was born in Paris in 1971 to a French general practioner mother and a German neuropsychiatrist father. My brother and I grew up in Berlin and enjoyed a liberal education, always in company of animals.

Actually I wanted to have a career as an athlete. My discipline was the 800m. But I had to end this career due to a triple torn ligament. Though I continue to do intensive sports, it‘s not as a professional anymore.

In 1987, I went to the United States for one year and graduated from Dublin High School in Ohio. I came back to Berlin in 1989. That was the year the Berlin Wall came down and we all lived a series of radical political changes.

I also graduated from German High School and then studied law. At the same time, I started traveling a lot, mostly alone; the camera was my constant companion.

X-RAY MAG: Why fish heads? How did you come to this concept and how did you develop your art work with fish heads over time?

ACBE: I was going for a walk on a sunny day in 1996, whistling, hands in my pockets. I was going, as usual, to the fish market, when a giant fish falling down from the sky said to me: “You!” Then I lost consciousness. When I woke up, I was told that a large fish-shaped restaurant sign got loose and hit me. Since then, I see fishes everywhere, in every area of the world. I have seen them working in factories, drinking, cheering, coming, bawling, dying... I’ve seen them on TV endlessly discussing modern times... Anyway, they are part of me now. Since then, I’ve learned that we do not see things as they are, but rather as we are. I started taking pictures at that very moment.

I went to a photojournalism school in Paris, and then I started a report on human being, through the fish, as man comes from the fish.

I was not looking for it; the fish imposed itself on me. Having said that, I have always been deeply grateful towards the fish; I have a true, deep empathy for it. I partially grew up by the sea, on the lower Normandy coast. I lived with fish. It was our food, our toys, and our life... The day it fell on my head, it became my obsession.

X-RAY MAG: What is your artistic method or creative process? How do you create your artworks and what do you do with the fish heads once you are done?

ACBE: A vague idea is born and matures. At a given moment, I have little idea of how to translate the idea into a symbol (because all my work is based on symbols and caricatures). I start drawing, specifying the lines and colors—they basically decide the dynamism of the image. Then I translate the drawing into a 1:1 proportion, to set the dimensions of different objects to build. The composition is about 2m wide and 1m high. Sometimes I change things along the way, random things appear quite often; it is a fragile but essential dialogue in my work.

The set up takes almost three months; the shoot takes 24 hours. On that specific day, I buy the fish. One fish can weigh up to 1.8km; they are quite big. I cut off the heads to put on the models; the bodies will be eaten. Life is a recycling process. The fish gets a second life and I can feed myself.

X-RAY MAG: What is your relationship to fish and the underwater world?

ACBE: As I said before, I partially grew up by the sea, in a small fishing town called Pirou Plage, across from Jersey. My brother and I learned snorkeling very early on, around four or five. We accompanied the fishermen. They explained their jobs to us and we became friends.

The sea taught me deep respect. I sensed a huge unexplored underwater world which impressed me infinitely.

Fishermen told me a bunch of superstitious stories, like weird noises they heard at sea they would attribute to mermaids, or sirens, creatures that were half-women-half-fish singing bewitching songs. I was six years old and wanted to believe them.

Underwater photographer Eric Hanauer gives a good description of the stories I heard: “Sailors had a fatalistic view of drowning. Most of them couldn’t swim, so even bathing in the ocean was considered a dangerous temptation of fate. The object of survival was staying out of the water, so nobody went in unnecessarily. If someone fell overboard, they might not even be thrown a rope because of the belief that their death was already preordained. ‛What the sea wants, the sea will have,’ was a fatalistic belief. Besides, a sacrifice to the sea gods might placate them so no more of the crew would follow ... The tides were thought to have an effect on death. If someone was gravely ill or wounded, death would come on ebb tide, as though life were ebbing away.”[2]

All these superstions became ingrained in me and nourished my imagination incredibly.

X-RAY MAG: In your relationship with fish and the sea, where have you had your favorite experiences?

ACBE: When I was little, maybe five years old, I was very impressed by the celebration in honor of St. Peter, the patron saint of fishermen in memory of the sailors lost at sea—a religious festival with a procession carrying the statue of the fishermen, the solemn Mass in the open air, the jettison of wreaths at sea.

In 1976 Pirou Plage had only 1,016 inhabitants, almost all of them were fishermen, so nearly every family had at least one person lost at sea; the St. Peters Day was taken seriously. It was the first time I saw the ocean full of roses and wreaths. It was very impressive.

X-RAY MAG: What are your thoughts on ocean conservation or sustainability in fisheries and how does your artwork relate to these issues?

ACBE: I agree with what Greenpeace has written: “You and I are alive right now because of the oceans. There is no other place in the universe so full of life as this planet—so green, so rich in diverse, beautiful, weird and wonderful, large and small species, on land and at sea—and it is all because Planet Earth is Planet Ocean.”[3]

Most fisheries can be made sustainable with current technology and management.[4] However, we all can make our small contribution to it, like, making safe, sustainable seafood choices, not purchasing items that exploit marine life, educating oneself about oceans and marine life, traveling the ocean responsibly and finally, following the ethos: “Ethics, too, are nothing else than reverence for life.“ (Albert Schweitzer)

I just read on the Greenpeace website that the longest mountain range on Earth is not on land but underwater. The mid-ocean ridge system wraps around the planet from the Arctic to the Atlantic oceans and is four times longer than the combined ranges of the Rockies, Andes and Himalayas.

Can you imagine that more people have stepped onto the moon than have gone down to see the deepest ocean trench? The explored regions of all the oceans amounts to less than five percent.[5]

When it comes to the oceans, we are ignoramuses. The ocean teaches me and nourishes my art and all relates directly to it.I want to do something wonderful, because I deeply believe in it. We can make a change in our minds, in the way we think, and call for ocean conservation to foster sustainability in fisheries. I believe in our future. I believe in the idea: “Do something wonderful, people may imitate it.” (Albert Schweitzer)

X-RAY MAG: You use a lot of humor in your pieces as well as more profound political statements. How do you come to your ideas and what or who inspires you?

ACBE: In 2011, I made a series of four pictures about what runs this world: money, guns, sex and drugs. In 2013, I started a series about our planet’s three major challenges: population growth, planet capacity and social cohesion. These topics are unlimited and our malaise is huge.

X-RAY MAG: What is the message or experience you want viewers of your artwork to have or understand?

ACBE: Being an artist also means having a responsibility, trying to think, asking questions, answering back, even being denounced.

I convey the message that the fish asked me to transmit. I am its voice, since it is silent! It has taught me that if I cannot con-trol my life, I can however control the way I see this world. I see that world through the fish, and I translate it in my compositions.

My pictures convey light or serious comedy. While they are entertaining, they also make us think, and even if the compositions are not real, they are always reflecting humor through the fish’s world.

Chaplin said: “In the creation of comedy, it is paradoxical that tragedy stimulates the spirit of ridicule; because ridicule, I suppose is an attitude of defiance: we must laugh in the face of our help-lessness against the forces of nature—or go insane.” (from My Autobiography, by Charles Chaplin)

X-RAY MAG: What are the challenges and/or benefits of being an artist in the world today?

ACBE: I agree with what artist, Lori McNee, has written: “Artists truly are the movers and shakers of the world. The ages demonstrate that artists have been at the forefront of every epic era. Oscar Wilde’s famous quote, ‛Life imitates art far more than art imitates life’, illustrates this. Art has been said to be 'an expression of both hope and despair', which embodies all facets of the human condition ... Art in all its forms, is a universal language ... the great equalizer and thinking agent. Art reaches across borders and connects the world ... I believe the worse things get, the more indispensable Art becomes.”[6]

X-RAY MAG: With all the press coverage you and your artwork have received, what opportunities have opened for you?

ACBE: I am more and more asked to stand up for environmental issues, which is what I like to do. It is our future. For exampIe, I recently accepted an offer to go to China for several months (Qiandao hu) to work on a cultural project about sustainability in fisheries and environmental ecosystems. They want a concept for a visual identity. There will also be an exhibition in a cultural center. It is exciting doing this in China.

X-RAY MAG: What insights have you gained from the process of showing your work to larger and different audiences?

ACBE: That it‘s worth continuing.

X-RAY MAG: What are your upcoming projects or events?

ACBE: Besides that project in Qiandao hu, China, I have been asked to make movies. I have been thinking about it for several years. I would love to have my characters come to life and to tackle a technique other than photography. We will make short movies for tv and for mobile apps.

X-RAY MAG: Is there anything else you would like to tell our readers about yourself and your artwork?

ACBE: I would like to express my respect for Anita Conti, the first woman oceanographer. Between the First and Second World Wars, she started to draw the first fishing maps, when, at the time, there were only navigational charts. Her scientific work helped to refine offshore practices. Already in 1939 she was alarmed at the overexploitation of the seas and the consequences of overfishing. Raising awareness of environmental issues, her findings showed that the ocean is not an infinite, limitless resource.[7] ■

For more information, visit the artist’s website at: www.acbe.eu

"My pictures convey light or serious comedy. While they are entertaining, they also make us think, and even if the compositions are not real, they are always reflecting humor through the fish’s world."

— Anne-Catherine Becker-Echivard

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #63

- Læs mere om X-Ray Mag #63

- Log ind for at skrive kommentarer