The Bahamas’ Tiger Beach: Petting Zoo or the Real Deal?

Tiger Beach in the Bahamas is firmly established as one of those global dive destinations of which almost everybody has heard. Its fame is largely derived from the many published images of its most celebrated visitor—Galeocerdo cuvier, the tiger shark.

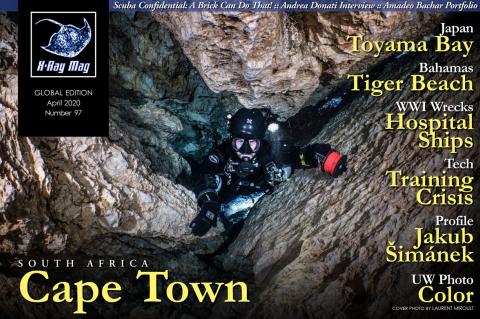

Divemaster strokes a tiger shark near the bait box behind him, Tiger Beach, Bahamas. Photo by Don Silcock.

Factfile

TIGER SHARKS

The tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) is the largest predatory fish in tropical seas. Tiger sharks get their name from the dark, vertical stripes found mainly on juveniles, which as they mature start to fade and almost disappear completely.

Their large, blunt nose and significant girth gives them a very commanding presence. They have a reputation as man-eaters and are considered second only to great white sharks in attacking humans. But because they are complete scavengers, with their predilection towards eating virtually anything, they are unlikely to swim away after the initial strike as great white sharks frequently do.

Tiger sharks are found in tropical and sub-tropical waters throughout the world. With the largest specimens reaching as long as 20ft (6m) in length and weighing in at more than 1,900 pounds (900kg). They are hunted extensively for their fins, skin and flesh, plus their livers contain high levels of vitamin A, which is processed into vitamin oil.

Tiger sharks have extremely low repopulation rates and long gestation periods, which makes them highly susceptible to fishing pressure, and as a result, are listed on the IUCN Red List as “Near Threatened” throughout their range.

--

GREAT HAMMERHEAD SHARKS

The great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) is a truly iconic shark, which typically grows to around 11ft (3.5m) in length and weighs in at about 500lb (230 kg)—although much larger specimens are seen occasionally.

It takes its name from its incredible hammer-shaped head, which it uses so effectively to hunt its favourite prey—stingrays. The front part of the “hammer” is where the ampullae of Lorenzini are located on great hammerheads, and they enable the shark to locate stingrays hidden in the sand.

The hammer-shaped head also enables great hammerhead sharks to pin stingrays down once they have been located. Typically, great hammerheads are solitary and nomadic predator creatures, which when in the presence of other sharks, such as at Tiger Beach, are given a wide berth.

Although potentially dangerous to humans, they are not known to be particularly aggressive and usually avoid divers completely, making good photographs difficult to achieve. Great hammerhead sharks are extremely vulnerable to overfishing and by-catch due to their low overall abundance and long gestation time. They are currently rated as globally “Endangered” on the IUCN Red List.

--

LEMON SHARKS

The lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris) is one the best known and most researched sharks because it is able to handle captivity for extended periods of time, thereby providing scientists with extensive opportunity to observe its behaviour. Adult lemon sharks often reach up to 3.5m in length and about 190kg in weight, making it one the larger sharks. Named for its bright yellow or brown pigmentation, it is found in tropical and subtropical waters in coastal areas of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, usually in moderately shallow water no deeper than 80m.

Lemon sharks are a social species and are often seen in groups, which have a structured hierarchy system based on size and sex, and are known for migrating from area to area, often over hundreds of kilometres to reach mating locations. They are viviparous, and females give birth to 15 to 20 live pups after a gestation period of around 12 months. Lemon sharks rarely if ever demonstrate any aggressive behaviour to each other or towards humans, and there has never been a recorded fatality from one of them attacking.

--

CARIBBEAN REEF SHARKS

The Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezi) is almost the shark from central casting. Its distinctive robust and streamlined shape, coloration, large eyes and short but rounded snout is so shark-like to the human eye! Found on the eastern coast of the United States and southwards down as far as Brazil, Caribbean reef sharks grow up to a maximum of 3m in length and weigh up to 70kg.

Although considered dangerous to humans, they do not have a history of attacks on humans and are generally passive towards divers, snorkellers and swimmers. They can, however, become aggressive in the presence of food, and if threatened, they will exhibit threatening behaviour by zigzagging while dipping their pectoral fins at intervals of one to two seconds.

Adults begin to mate once they reach between 1.5 to 2m in length, but the reproduction cycle is long because females only get pregnant every other year and the gestation period is another 12 months. Caribbean reef sharks are viviparous, and the usual litter size is four to six pups, which are about 0.5m long when born.

Tiger sharks are considered one of the “big three” most dangerous sharks, and along with the great white and bull sharks, are believed to be responsible for the vast majority of unprovoked attacks on humans. They are renowned for their inherently predatory behaviour in which, much like their terrestrial namesakes, they close in on their intended prey slowly and silently before pouncing with deadly efficiency.

They are also infamous for consuming almost anything and are often referred to as the “garbage cans of the sea,” since inspection of dead tiger sharks’ stomach contents have revealed everything from sheep, goats and even horses, to bottles, tires, license plates and (believe it or not) explosives!

Tiger sharks are one of the ocean’s largest sharks and typically grow to between 3m and 5m in length and weigh in at around 350kg to 700kg. They are formidable creatures with an intimidating reputation. So, how can it be that week after week in the season, dozens of divers enter the waters of Tiger Beach for open-water, eyeball-to-eyeball encounters?

Tiger Beach is not a beach

Physically, Tiger Beach is about a square mile in overall size and is located on the western edge of Little Bahama Bank, about 30km west of the town of West End on the north Bahamian island of Grand Bahama. And the first thing you need to know about Tiger Beach is that it isn’t one—it is actually a shallow sand bank that looks like there is a beach nearby.

The general area used to be known locally as Dry Bank and was first dived by Captain Scott Smith of the Dolphin Dream liveaboard back in the late 1980s. But who actually started the whole shark diving thing is the subject of great discussion.

Smith would seem to be the person who started tempting sharks to the stern of Dolphin Dream on those early trips, and the first published tiger shark images apparently were captured from the boat. While the legendary Jim Abernathy, owner of the Shearwater liveaboard, seems to be the person who first took bait boxes into the water in late 2003. Abernathy is generally credited with starting the process of tempting tiger sharks with the bait boxes and was the person who renamed the area “Tiger Beach.” Whoever did what does not really matter now, but what does matter is that we divers and underwater photographers owe a significant debt of gratitude to both Smith and Abernathy for creating what has become the premiere location in the world for tiger shark encounters.

Understanding Tiger Beach

The Bahamas are said to take their name from baja mar—which is Spanish for “shallow seas”—because the archipelago of 29 main islands and roughly 700 cays that form the country reside on top of two main limestone carbonate platforms called the Bahama Banks. The Great Bahama Bank covers the southern part of the archipelago, and Little Bahama Bank covers the northern part, with incredible channels as deep as 4,000m separating the two.

Those channels are flushed with the clean rich waters of the Atlantic Ocean, as the Gulf Stream makes its way through the Caribbean and then up the Florida coast. It is the combination of those rich waters and the shallow, sheltered cays and reefs of the Bahama Banks that make the area so prolific.

Satellite tagging of tiger sharks in Bermuda has revealed two really interesting facets of their behaviour. Firstly, they spend a lot of time at the surface, which is believed to be related to feeding and hunting patterns. Secondly, their migration patterns are very consistent, with five to six months of the northern spring and summer months spent in the open Atlantic Ocean to the north and west of Bermuda, followed by a migration south to the Bahamas where they spend the autumn and winter months.

It is believed (but not yet proven) that the months in the open ocean are related to mating and feeding on the migratory loggerhead turtles that pass through at that time of year, while the time spent in the Bahamas is related to gestation, as most of the tiger sharks observed at Tiger Beach are females and many of them are pregnant. Clearly, if the Tiger Beach area is the “tiger shark nursery,” it appears to be incredibly important to the long-term conservation of these animals, which are currently on the IUCN Red List as “Near Threatened” and have a declining population globally.

Conservation in the Bahamas

This island nation in the Atlantic Ocean, famed for its picturesque beauty and crystal-clear waters, has in many ways led the world in marine conservation. Although far from perfect, and indeed guilty of allowing periodic over-exploitation of its fish stocks together with the development of tourist resorts in ecologically sensitive areas, the Bahamas was the first country to establish a marine protected area (MPA).

That was way back in 1959 when the Bahamas National Trust was established to manage the 112,640-acre Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park in what can now be considered as an incredible piece of foresight. The Bahamas have since added another 26 national parks, covering over one million acres of land and sea, together with enacting substantial supporting environmental legislation, including making Exuma Cays a no-take marine reserve in 1986. Then, in 2011, the government went one step further and became the fourth country in the world to establish a shark sanctuary by formally protected all sharks in Bahamian waters.

Shark tourism in the Bahamas

While establishing the Bahamas as a complete sanctuary was an excellent step forward for shark conservation generally, it was also tacit recognition of the significance of sharks to the overall health of Bahamian fisheries. The marine environment is a complex and multi-faceted thing, but if there is one global truism, it is that everything has its place in the greater scheme of things, and 400 million years of evolution have produced what could be referred to as a “fine balance.” Sharks are a very necessary part of that balance and can be thought of as the masters of their ecosystems. Their role at the top of the marine food chain is to clean up the oceans with ruthless efficiency—the very thing that seems to most intimidate us humans!

Without sharks, the dead, the dying, the diseased and the dumb of the oceans would pollute and degrade the health of those ecosystems and the genetic quality of its inhabitants. The many species of sharks are there for a reason, and they have evolved superbly, in true Darwinian fashion, to execute their mission. Remove the sharks and disruption occurs, something marine scientists refer to rather prosaically as “trophic cascades.” Think of the shark as the first in a long line of finely balanced dominos, and if it is tipped over, the rest start to go down as well.

But all that said, there is also the cold hard fact that a live shark is worth a lot more in tourist dollars than a dead one. With one study published in 2017 indicating that 99 percent of the almost US$114m in annual revenue generated by the Bahamas dive industry came from shark tourism.

Eye of the tiger

Arriving for the first time at Tiger Beach is somewhat of a soul-searching experience. It is one thing to read and hear about the sharks that congregate there, but quite another to actually be there preparing for that first dive—particularly when there are up to a dozen two to three-metre sharks circling the back of the boat and lots of others visible in the clear waters!

The briefings provided on these trips are both extensive and exemplary, with everything clearly explained in a logical and nonsensational way—from how to prepare to go in the water to how to enter the water and what to do when under the water. But the fact of the matter is that waiting for a gap in the patrolling sharks and then carefully rolling in amongst them is not something you do on a daily basis.

Once underwater, however, nerves settle, and an awareness starts to form for the sharks and their behaviour patterns. From the pushy way the Caribbean reef sharks approach and tend to work in a bit of a pack, to the sneaky way the large lemon sharks come in low to the bottom, with a leery look straight out of one of those horror movies.

But that new awareness fades to grey when the first tiger shark arrives. Tiger sharks have an incredibly commanding presence that indicates they know their place at the top of the food chain. They move slowly and carefully, checking out what is going on, and the other sharks clearly defer to them.

The protocol at Tiger Beach is not to even worry about the lemon and reef sharks, as the only real chance of being bitten is if you break the cardinal rule of getting too close to the bait box. Even then, a bite is unlikely to be life-threatening, but you should always know where the tiger sharks are, and you should always face them—literally keeping the eye of the tiger in view at all times!

Tiger sharks are intelligent and curious animals, which tend to approach divers because their sensory systems pick up the tiny electrical and audible signals emitted from our instrumentation and photographic equipment. They will tend to bump with their snouts, as they investigate the stimuli further, and there is always the chance that they will use their mouths. As their jaws are so powerful, even a gentle nip would be life-threatening. So, photographers are instructed to use their cameras as shields, with the strict instruction to let go if a tiger shark decides to do a taste test—but remember to press the video button.

Petting zoo?

Being in open water with so many large and potentially very dangerous sharks verges on a life-changing experience. It really is a big deal to be there, and the first few days are a kaleidoscope of feelings—fear, awe, intimidation, excitement and an incredible sense of adventure at what you have done.

Then, a degree of complacency starts to settle in as you begin to think that maybe these animals have simply been misunderstood all along and they are really just kind and gentle creatures. This, for me, is when Tiger Beach becomes dangerous, because you are in a very special place where these creatures are both protected and well fed naturally, plus they get the snacks from the bait box. So, you are not really seeing them in their natural environment and, in a way, yes, it is a kind of petting zoo.

Or the real deal

Tiger Beach is quite unique in that there really is nowhere else like it. Where else can one can be in open water, in “relative” safety, with so many large and potentially dangerous sharks?

The relative safety comes from the fact that the sharks at Tiger Beach have basically become accustomed to the presence of divers and, because they have plenty of other things to eat, they do not regard us as a principal food source. So, while it is absolutely not a completely natural setting, there is simply nothing else like it, if you want to see these creatures up-front and personal. It is the real deal! ■

Asia correspondent Don Silcock is based in Bali, Indonesia. For more information and extensive location guides, articles and images on some of the world’s best diving locations, check out his website at: Indopacificimages.com.

Download the full article ⬇︎