In some developing countries, dolphin and whale watching is not very common. In Madeira, the authorities, biologists and whale-watching operators are working together to promote conservation and research. They aim to ensure that visitors can continue to enjoy amazing encounters with these animals in the future. Daniel Brinckmann has the story.

Contributed by

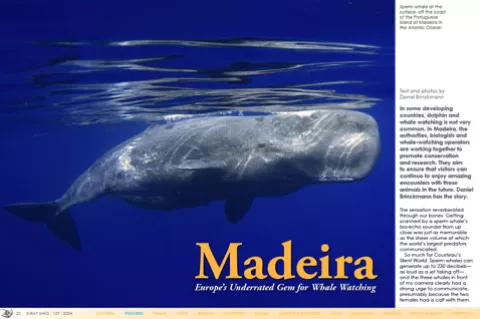

The sensation reverberated through our bones. Getting scanned by a sperm whale’s bio-echo sounder from up close was just as memorable as the sheer volume at which the world’s largest predators communicated.

So much for Cousteau’s Silent World. Sperm whales can generate up to 230 decibels—as loud as a jet taking off—and the three whales in front of my camera clearly had a strong urge to communicate, presumably because the two females had a calf with them. While the second massive whale positioned itself protectively in front of the young one, the first began its descent process as if in slow motion, followed by the other two after a brief pause.

Even before we reached the boat after our encounter with the whales in the water, skipper Daniel Jardim was already gesturing and shouting, “Two o’clock... swim, swim, swim.” A little over a hundred metres farther out in open sea off Calheta, another whale with its offspring came into view.

Both dolphins swam towards us unfamiliar humans in the water without changing their course. Then, they calmly dove down five or seven metres while keeping a constant eye on us.

Before the dolphins departed, marine biologist Paula Thake had managed to collect a few dark grey scraps of skin, which looked like pieces of trash bags, and placed them in a prepared sample cup on board the boat. Thake, a German-speaking Maltese woman, and her partner Daniel work for the whale-watching operator Lobosonda, providing new data for research colleagues on the mainland.

Samples obtained

Biologists Luís Freitas, former director of the Madeira Whale Museum and now head of the scientific department, and Filipe Alves from the MARE/ARDITI Centre for Marine and Environmental Sciences were pleased with the recent sighting data and the new samples obtained. These samples contained genetic material that could be used for future studies.

According to Freitas, these samples are being stored with information on their origins until enough DNA samples are collected to conduct ecotoxicological studies. These studies will help in drawing conclusions about relationships, population comparisons, and migratory movements of marine animals between Madeira, the Canary Islands and the Azores. The latter is also being investigated in cross-archipelago cooperation between scientific institutes and projects such as Mistic Seas Macaronesia, MARCET II and the Whale Tales Project. Specific animals are being identified using photo databases to which whale-watching crews and guests can contribute their images.

At the moment, scientists from both Portuguese archipelagos are collaborating to study the impact of human activities and the potential stress caused by whale watching as part of the META (Marine Mammal and Ecosystem: Anthropogenic Threat Assessment) project. The research focuses on frequently present local herds, with the goal of establishing protective measures for them in specific areas of high activity.

Rich feeding ground

For example, in the village of Calheta, a deep-sea canyon near the coast provides a rich feeding ground for various types of whales and dolphins. These include large baleen whales benefiting from rising plankton during their spring migrations into the North Sea, as well as permanent residents such as pilot, sperm and beaked whales hunting for squid at the bottom of the abyss, while bottlenose dolphins hunt for fish in the shallows.

In addition to the year-round species, blue, fin, humpback and minke whales pass by the island in spring, and the latter two sometimes return in autumn. Due to its location off the African coast, warm-water lovers such as Bryde’s whales are also regularly found off Madeira, especially in summer—and the trend is rising. Freitas confirmed that “the migratory animals first come to Madeira to feed. They also stay in our coastal waters to breed and rest, where the young are safe, but they can’t do it without an energy supply, and the subtropical open Atlantic is low in nutrients.”

End of whaling

Between 26 and 29 species of marine mammals can be found off Madeira, also known as the Island of Eternal Spring, with dolphins being the most frequently observed from boats. Despite this, and several scenes shot here for the 1950s film classic Moby Dick, Madeira has not been very popular with dolphin lovers.

The region had a brief era of whaling, which ended in 1981, and it took more than 20 years before whale watching became a commercial activity. However, in 2013, stricter laws were put in place due to the flourishing whale-watching industry, regulating boat distance, manoeuvres and observation times.

Snorkelling with whales and dolphins had not been expressly prohibited before, but now encounters with Atlantic spotted dolphins (in summer and autumn) and common dolphins (in winter and spring) are only permitted off Madeira, with one hand of the snorkeller remaining on the boat or on a rope with buoys pulled behind the boat, as practised by Lobosonda. According to Thake, this open sea approach offers more safety and advantages in observation, as the animals feel more comfortable and have the chance to initiate encounters themselves rather than being approached or pursued by snorkellers.

Playful dolphins

The following day, we witnessed firsthand what the researchers had explained to us. Even before one of the three herds of spotted dolphins approached the whale-watching boat Stenella, seven snorkellers held onto the boat’s rope and were pulled through the water. Shortly after, more than 20 Atlantic spotted dolphins swam and played between the bow wave and the last buoy, swimming under us in small groups and keeping their eyes fixed on the yellow rope.

The speed of the boat ensured that the animals did not lose interest quickly. Many snorkelers would be well advised to take the occasional look over their shoulder. Almost a dozen times, a cheeky spotted dolphin stalked us in our blind spot and came within two metres.

“That’s typical of these animals,” said Thake with a laugh after the 20-minute encounter. “For me, they are ‘street-smart’ and don’t just mix with groups of other species. I’ve seen them annoying other dolphins or even sperm whales and turning turtles on their backs.” In other words, they are ideal “snorkelling dolphins.”

Legal method

Whale watchers who want to take a photo for a whale poster to hang above their bed can use a two-metre-long pole with a thread for “action cams” to take close-up shots from dry land. Skipper Jardim confirmed that as long as your feet remain on board, there is nothing to stop you from using underwater camera housings.

“Sometimes young sperm whales swim curiously towards the boat and come closer than the 50-metre distance rule allows. In those cases, we turn off the engine,” he said. He also emphasised the importance of adhering to a code of conduct: “Imagine someone suddenly starting the engine in the middle of a group of whales without a second thought.”

The regulations protect us by providing precise instructions on how to behave. These rules of behaviour are issued by the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (IFCN) and are constantly revised by biologists to improve encounters between humans and animals. Additionally, biologists hold regular training courses for whale-watching crews to ensure proper adherence to these rules.

Successful model

The collaboration between scientists, ecotourism providers, and guests is a successful model, emphasised by Filipe Alves from MARE/ARDITI. He stated, “The incredible number of observations and data from whale watchers, who are out at sea practically every day, is of great value to our research group.”

Additionally, Freitas highlighted the positive current results on the interaction between ecotourism and the welfare of the animals, stating, “Human activity around Madeira is at a level that does not keep whales and dolphins away from our coasts, and such a stable situation is a good sign.”

Anyone coming to the archipelago to visit groupers and moray eels should consider spending a day or two whale watching and snorkelling with dolphins. On a good day, this decision can make the difference between a great diving holiday and a fantastic one.

Operator

The whale-watching operator Lobosonda in Calheta offers whale- and dolphin-watching expeditions using a modern speedboat that can accommodate up to 12 guests. They also use a traditional fishing boat, going out to sea two to four times a day (except on Sundays) for two to three hours during the winter season. Additionally, they offer dolphin snorkelling experiences. You can find more information on their website at lobosonda.com. Tip: Combine your dolphin snorkelling with diving at Manta Diving in Canico. See: mantadiving.com. ■